Artifacts of a Panic -- Early 90s Edition, Part 2

Part 2 of my highly timely deep-dive into "PC" "dictionaries" from the 1990s!

[Hey all, in this series I’m working with objects I found during my research for The Cancel Culture Panic, but that, for whatever reason, didn’t make it into the book. I’ve decided to open the comments on these — because I thought it might be fun to read and analyze these together. I’ll try to provide a lot of quotations and pictures in posts like this, to give you a chance to explore these objects in more detail. Let me know if you think I’ve made a mistake, or failed to notice something fascinating about these objects. Thank you for venturing into the cursed mines of PC-discourse with me!]

In last week’s entry, I went through one of several dictionaries of “PC”-language. This was a strange kind of mini-genre that proliferated pretty much only in the mid-to-late 90s. I’m inclined to chalk up that rather brief moment in the sun to the fact that the very idea of the dictionary as a thing you purchase was starting to take serious hits by the mid-90s. The first digital dictionaries were already around. If there are any computer historians among my readers, you can perhaps correct me, but I feel like I recall my parents’ i586 coming with a CD-Rom (?) of a dictionary for sure, in — what? — 1993? So the “political correctness” dictionary’s heyday actually coincided with the moment such books became actually less common in peoples’ houses. There may be a generational element here as well; but also an intergenerational element. The English books strike me as books you buy and gift more than books you buy to read yourself. A lot of joke books work this way, of course. So it becomes a way of signaling intergenerationally (“lol, get a load of these mooks”), but also perhaps a way of signaling across generational lines — especially the thin-on-content American editions that seem to draw strongly on National Lampoon-style or Mad Magazine-stye imagery may have been intended for older folks to give to younger folks. I.e. the very people whose language changes made up something like 60% of the content.

Of course, they aren’t really dictionaries — you can’t really refer to the weird hodgepodge of topics their authors decided to slap between their covers. I forgot the individual entries the moment I closed the respective book, selection and organization are altogether haphazard. A bunch of these stop being “dictionaries” and just abandon the bit halfway through. Granted, they look more like dictionaries than, say, FOX News host Jimmy Failla’s Cancel Culture Dictionary, which just came out this year. Failla’s book is simply a set of little chapters arranged alphabetically (a chapter on the Dukes of Hazzard (oooh, topical), one on Ellen, etc. etc.).

The “PC”-dictionaries still had proper entries, illustrations, etc. But even they were — at least in the US and the UK — really joke books written by professional comedy writers. (Jimmy Failla, too, is a former New York City cabbie, comedian and radio host, whose qualifications for writing a book about cancel culture consist of hosting the satirical news show Fox News Saturday Night.) This makes sense, because “PC” dictionaries were not actually about the phenomenon they were purported to be about — they just kind of served up “edgy” (read: anything but edgy) comedy on the theory (so beloved in the 90s) that surely someone somewhere was offended by their brash truth telling about how men were all like this and women were all like that.

Think of how many comedians did a pretty straightforward “politically incorrect” shtick in the mid-90s. They all depended on this basic sense that someone was offended — in their hands the “politically correct” were essentially props. And the US/UK “dictionaries” I found work much the same way. But they’re not straightforwardly comedic, and their tone is therefore a bit different. Look at the subtitle of Nigel Rees’s Politically Correct Phrasebook: “What they say you can and cannot say in the 1990s.” There’s more of a conspiratorial edge to the framing (especially when compared to the cover on the left). These authors aren’t so much using feminists, POC, or some imagined version of them as props to lard up otherwise listless jokes — they feel actively oppressed and angry at them. The affect is far nastier and more genuinely aggrieved than, say, Denis Leary’s “I’m an asshole”-persona in his standup act, and simply more unhinged and shouty than Bill Maher’s smirky above-it-all-ness.

This is the tone I found amplified in the French dictionaries, which — as I pointed out last time — were not by professional comedians, but rather put out by politicians. Where the English ones (like the one below) can feel scattershot and unfocused, the French ones seem monomaniacal and straightforwardly reactionary.

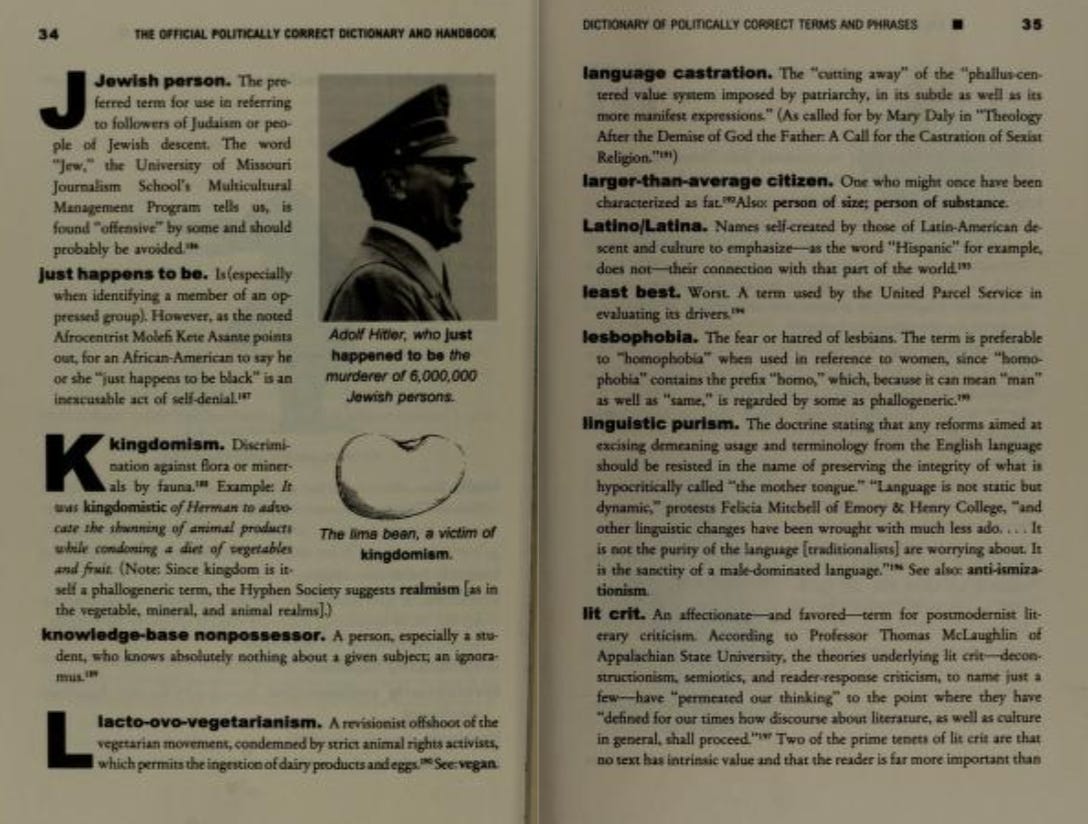

[from The Official Politically Correct Dictionary and Handbook by Henry Beard and Christopher Cerf]

Who exactly are “the politically correct”?

Phillippe De Villiers’ Dictionnaire du politiquement correct (1996) isn’t meant to be funny. I think? It at times sneers in a tone that simulates caustic wit, but while in other “dictionaries” of the time the jokes don’t land, here they simply don’t exist. The entry for “Leftist intellectuals” simply reads: “pleonasm”. That entry also foregrounds that there is a problem of focalization in the book: some entries (like “pleonasm”) are written in the voice of the “politically correct”. Others are clearly descriptions of “politically correct” positions from an outside position.

The thing I pointed out about “political correctness” above — the fact that these books seem to have no interest in the subject they’re ostensibly all about — is doubly true here. “Le politiquement correct” for de Villiers comprises stuff a lefty might say, or a socialist, or a bureaucrat in Brussels, or, or, or. There’s no coherence to the project he describes, other than that he doesn’t like it. The euro is politically correct (he still calls it “ecu”, which took me back), so is the movie La Haine (because it has non-white people in it and shows them as people, I guess?), so is AIDS, so is the late conductor/composer Pierre Boulez, so are taxes, so are public schools, so is “Franco-German unity.”

This is something you find a lot when you look at 90s discourses about “PC”: it’s hard to imagine a person who simultaneously holds even half the beliefs ascribed to “PC”; but it is quite easy to imagine the person who finds them all really annoying. Cancel culture, according to the cover to Failla’s book, is a “war on fun.” And the framing of US/UK books about “PC” alway suggests that whatever the opposite of “PC” is is side-splittingly hilarious. It usually isn’t, but note that de Villiers’ book jettisons even that suggestion of fun. If you met someone at a party who was just rattling off the list of euroskeptic and anti-modern grievances he trots out in his book, that person would be an absolute bore.

But perhaps more importantly, de Villiers’ book is not really about language. It’s kind of remarkable — “PC” was all about language wars in the 1990s, about what you weren’t allowed to say, what words you were supposedly not allowed to use. And the dictionary as a genre points to language use as well — one reason presumably why people turned to the dictionary to make fun of “PC”. But de Villiers’ thesis doesn’t seem to be that you have to say “Euro” or “Pierre Boulez” or whatever. He seems to object to their existence, or disagrees with the way (some) people are talking about these topics. Or, as I put it in my book: he experienced shifts in public opinion (on Europe, on sexuality, on feminism, on nationalism) or simply shifting trends (the presence of immigrants in various walks of life, European integration) as conspiratorial and oppressive.

Why do I bring this up? My friend and podcast co-host Moira Donegan said something very wise a few weeks ago. For all the complaints about “coddling” when people yell about language change, a lot of the people who complain basically “need to have their own outlook and choices affirmed at every turn”, and completely freak out when that doesn’t happen. “What they say you can and cannot say anymore in the 1990s” was the subtitle of the Rees-book in its UK edition. But in 99% of cases, the more accurate subtitle would have been: “What some people are saying differently from you in the 1990s”.

In an entry on “Latino/a” from The Official Politically Correct Dictionary and Handbook (which I reproduced above), the authors note with evident pique that “Latino” and “Latina” are “self-created names”. That’s the sin, for them. That people self-describe, rather than being described by the kinds of people that traditionally author dictionaries. It’s not anything about the descriptor, it’s an objection to the act of self-description.

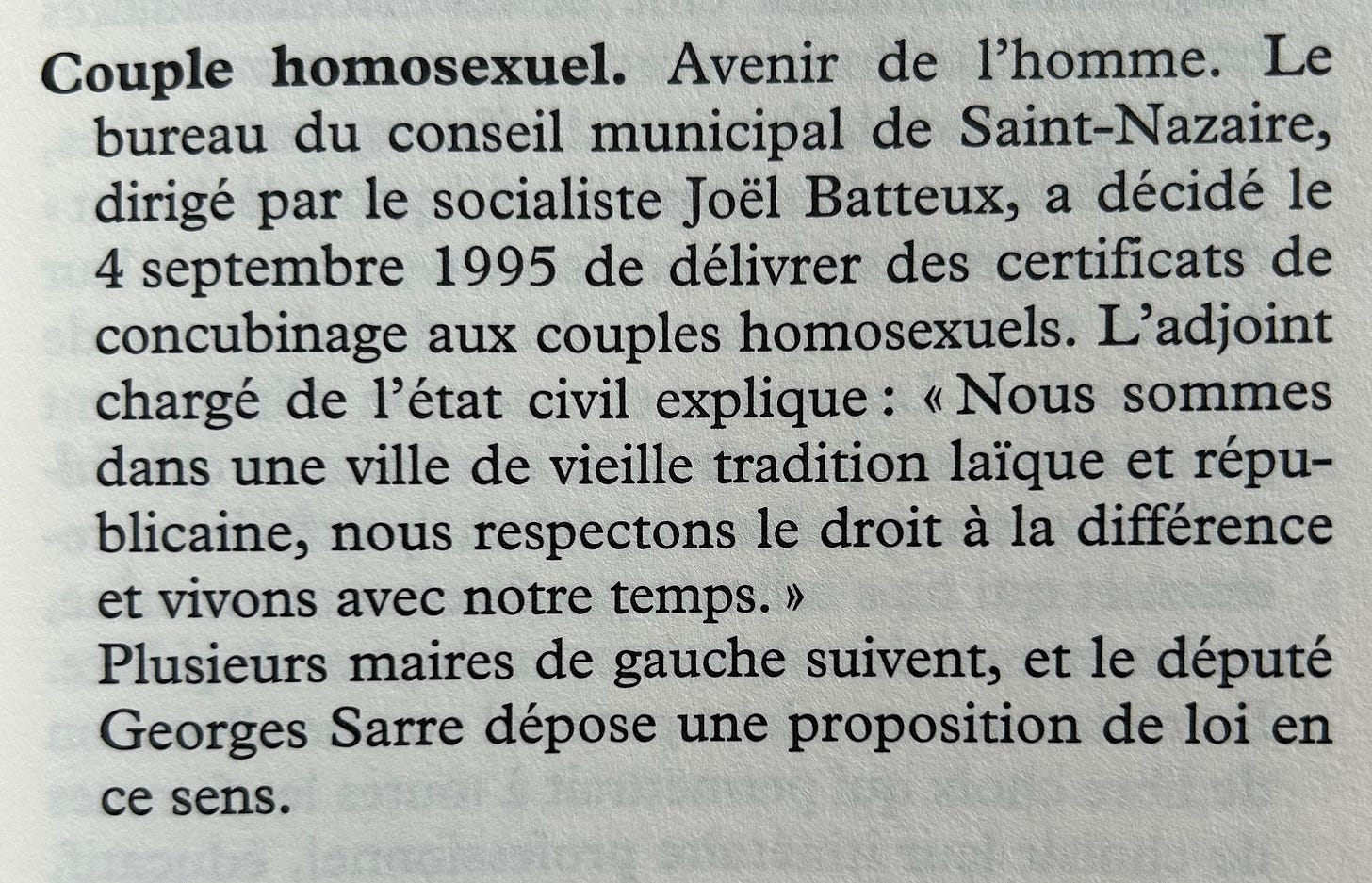

Take for example de Villiers’ entry on “homosexual couple.”

Here’s the passage in English:

“Homosexual couple. Future of man. The Saint-Nazaire municipal council office, led by the socialist Joël Batteux, decided on September 4, 1995 to issue cohabitation certificates to homosexual couples. The deputy in charge of civil status explains: 'We are in a city with an old secular and republican tradition, we respect the right to be different and we go with the times.' Several left-wing mayors followed, and the deputy Georges Sarre submitted a proposed law to similar effect.”

Just in case you’re not up on your French history: same-sex marriage became legal in the country in 2013, fully 17 years after this book went to print. By the late 90s, there was a concerted push towards PACS (pacte civile de solidarité, akin to a civil union), and there was some activist clamor around the issue on the left. And apparently there was the city of Saint-Nazaire, a university town of 70,000 on the Loire Estuary, which ended up giving some people rights de Villiers thought they should not have — whatever came of it, I didn’t find any mention of this anywhere. De Villiers turns that into “The future of man [sic].” Some people in French society experienced minor forbearance and grudging recognition; de Villiers experienced the same process as a dictatorial imposition of “politically correct” groupthink (by the municipal council’s office of a single small town).

It took me a while to notice, but what makes de Villier’s dictionary a dictionary is not its organization or its language — it’s the pose of alienation. A dictionary has to take a maximal distance, a kind of space-alien remove, from everyday language, has to imagine a reader tremendously unaware of how a particular word is used. It has to abstract from pragmatics, from the way we naturally live with words. And that’s the way de Villiers positions his Dictionnaire: it takes a maximal distance from the messy business of a changing society and looks askance at things that society just kind of does and/or accepts. That’s not a bad pose, of course. Estranging ourselves from the everyday is a really central way of reflecting on it.

But de Villiers goes the extra step of expressing a kind of carping disapproval at every step. He never comes out swinging against whatever it is he is railing against (which is most things). He always seems to do two things at once: he sort of accepts that this is how we all talk now, but registers that he doesn’t like it one bit. Except that that’s utter horseshit on both counts: “we” didn’t talk like that in the 1990s; and the position that didn’t like the tentative language changes was large (possibly a majority), and quite clearly dominant in society. Otherwise his example didn’t need to be something some clerk in Saint-Nazaire did; it could be the passage of gay marriage legislation. Anti-immigrant violence and racism were huge problems in France in the 1990s, but he presents an embrace of mass immigration as somehow the new orthodoxy. Unless you happened to live in Saint-Nazaire apparently (?), you couldn’t get married as a gay person in France, but he presents homosexuality as the inevitable “future”.

“Gender” before “Theory”

What I think is deeply valuable about these curios from the depths of the “PC”-panic era, is that they give a pretty good sense of how long some of these language wars have been with us. Their philippics against supposed academic or activist jargon (“kindomism”, or the ubiquitous “phallogocentrism”), their obsession with hyphenation, their insistence that anything involving homosexuality is inherently ridiculous (I guess our homophobes have updated this shtick slightly and shifted it to trans people?): it all really gives you the sense that we’ve never quite moved on from the mid-90s. But in some way the subtle shifts that there are shed a light on our contemporary discourse. Take a look at the entry for “gender” in the Dictionnaire:

Here’s the passage in English:

“Since the Beijing conference, there are no longer two sexes: male and female. According to the conclusions of the experts of global correctness, this division of humanity indeed stemmed from a very old oppressive prejudice. From now on, we have to talk about gender. In the European Parliament, speakers conform to this new logomachy. There are therefore five genders: male heterosexual, female heterosexual, male homosexual, female homosexual, transsexual. These five genders are not only equivalent but on their way to statistical equality.”

Perhaps it’s because I recently read Judith Butler’s new book Who’s Afraid of Gender — the podcast episode on it should be out today or tomorrow —, but it’s really noticeable how this passage combines some tried-and-true standards of the “PC”-genre (“our normal way of talking is now considered prejudice!”) with some stuff that the anti-”PC” warriors usually pushed into the quiet part. Note that de Villiers doesn’t mention the universities, "“theory”, or weird young people (the “blue-haired girl”, for instance, who has been making an appearance in a lot of anti-woke media in the last half-year). This is straightforwardly a conspiracy narrative about the UN and the EU. That — as Butler points out in their book — certainly true of Victor Orbán’s invocations of “gender theory”.

And I don’t know how to interpret that final line — that these five “genders” are “on their way to statistical equality” — other than that this is straying into “great replacement” territory. Unless there’s a nuance in the French I’m not getting, how would we get “statistical equality” between the five groups de Villiers describes, other than either forcing people to be gay, or recruiting extra gays? (I should mention that the entry of “nation of immigrants” definitely has more than a whiff of Grande Remplacement ideas, so I’m not pulling this out of thin air.)

I think that’s interesting, because it suggests what the positioning of “gender” as “theoretical” was key to the success of “gender” as a thing people could freak out about. My friend Moira Weigel recently wrote an excellent article about “Hating Theory” — it’s worth checking out on this. This is the fear of gender before those afraid of it could attach it to a theory. At least in this case, the critique of academicism thus became a way to launder certain ideas that — in their pure, uncut form — were too obviously far right fever dreams. But slap the moniker “theory” on it, and you could make the same point and have sage centrist editors nod along to it.