Artifacts of a Panic -- Early 90s Edition

Reading the various "dictionaries" of "Political Correctness" -- Part I

For today’s cancel culture artifact I’m going back in time. Meaning: it’s not about “cancel culture” per se, but about the predecessor term “political correctness”. “PC” emerged into broader consciousness in the early 1990s, and made quite a splash internationally. Like cancel culture, “PC” was often about universities, it was about censorious elite leftists, about self-censorship, and it was very much about language wars. Think of an article like John Taylor’s “Are You Politically Correct?” (January 1991), which in its framing (below you can see the cover and the opening spread of the article) positions “PC” almost entirely as being about using one word rather than the one you used to use:

The question “[Do I say] ‘Pet” instead of ‘Animal Companion’?” already points to what was so interesting about these language wars. They were largely a creative endeavor. Yes, every article like this contained a number actual language changes — but it also contained ones that were at best recherché (the chance of being “accused” of “logocentrism” outside of an Interpretation Theory seminar at Swarthmore College in 1991 was probably as near to zero as anything can be), and in the worst case just made up. Or, as John Wilson pointed out in The Myth of Political Correctness, a joke about which people had forgotten that it was a joke.

When pressed, the authors and editors could always say that they were exaggerating for comedic effect — but take another look at these two pictures. Does that freaked out white woman look particularly amused to you? Or does she look anxious about whether her “logocentrism” might be showing? And do you get particularly comedic vibes from the pictures that accompany the article subhead inside the magazine — in case the resolution isn’t good enough, it’s a picture of red guards and one of Hitler Youth burning books. The language war are always pitched halfway between humor and hyperbole — it’s unclear what the latest freakout about language change is about, if most of the examples are at best amusing. Clearly something fairly serious must be happening. But how come whatever it is has to be constantly buttressed by examples that lapse into self-parody?

In this installment and the next, I want to focus on this particular aspect of the language war. A lot of the fights over language during the cancel culture panic fairly exactly mirror those of the PC fracas. But of course our publishing landscape is no longer the same. Some things have stayed the same — big, ambitious cover stories in national newspapers for one.

But others are new. One thing the anti-“PC” wave brought into at least some bookstores and presumably also into some households (though more on that later) are PC-“Dictionaries”. These appeared rather quickly, in several languages, then disappeared again pretty fast.

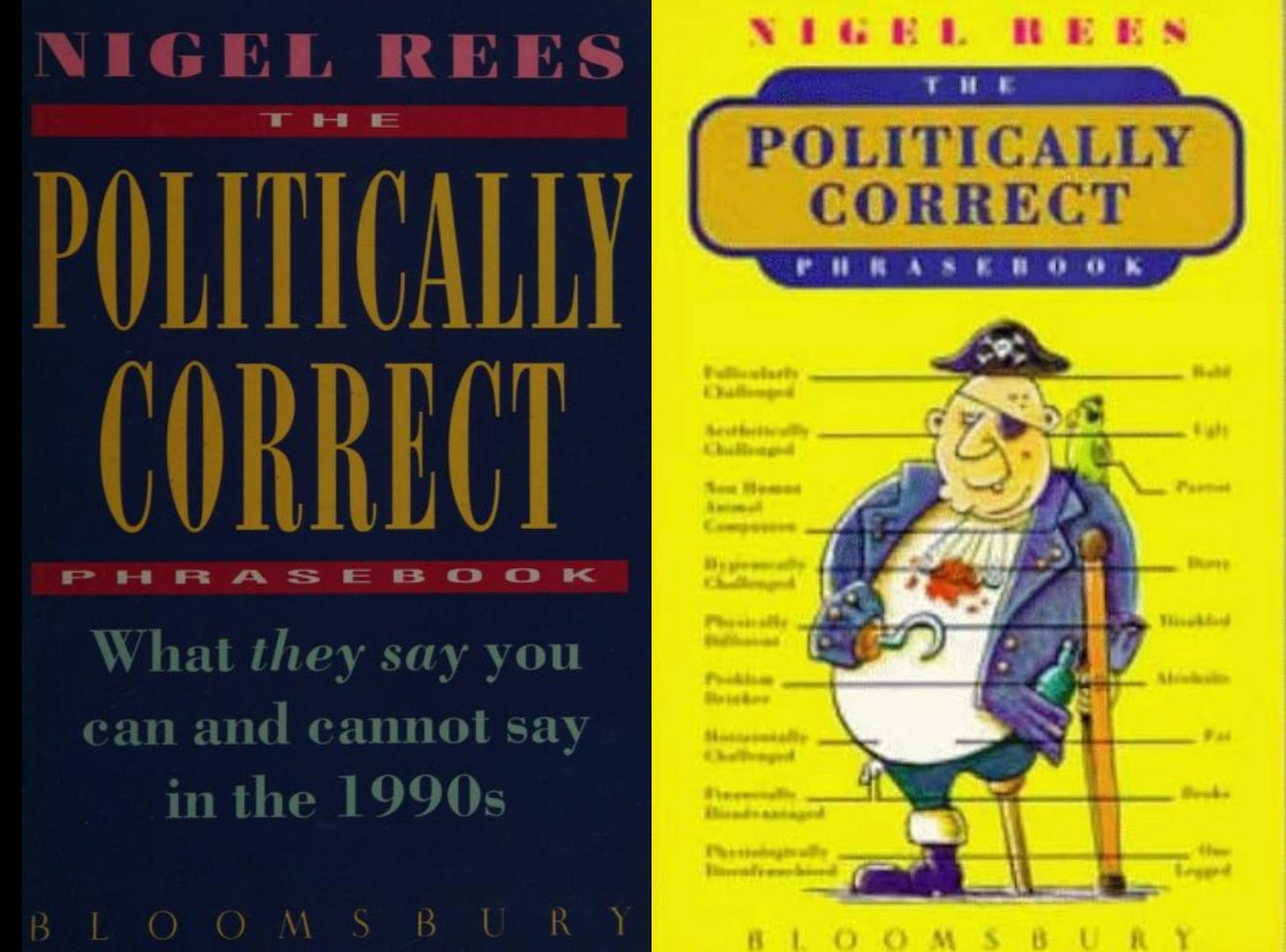

The official politically correct dictionary and handbook by Henry Beard and Christopher Cerf came out with Villard Books in 1992. It apparently did extremely well at the time. It was one of several. Below is Nigel Rees’ The Politically Correct Phrasebook, which came out with Bloomsbury in 1994. Both of these books were from professional joke-book writers — Beard and Cerf had a background with National Lampoon, Rees was a TV show host who wrote humor and quote books.

What I only realized in researching The Cancel Culture Panic: there was a similar crop of books in France, pretty much around the same time. André Santini (a politician of the conservative UMP) published De tabou à boutade: Le véritable dictionnaire du politiquement correct in 1996. That same year Philippe de Villiers (member of the National Assembly and Minister of Culture under François Mitterand) published his Dictionnaire Du Politiquement Correct à la française. I will talk about these books in more detail next week — they’re fascinating, and fascinatingly different from their Anglo-American cousins. For now, I just want to point out that this was clearly an idea with legs.

My theme today will be that in these books the carnivalesque and the self-serious enter into some kind of weird alliance. Are these books funny or a serious warning? They never seem to decide. You might think that the more button-up look in the French books may reflect a difference between the fate of the concept of “PC” in French publishing. But I only showed you one cover for Nigel Rees’s book. Here are the covers of the two editions I could find:

These are the covers to the same book! They couldn’t be more different tonally — to me the left one says “serious book for serious people concerned about today’s serious problem”, the left says “eh, you’re late to the party and your pre-teen nephew might like this”. In the event, it’s neither of these two. I’m obviously a humorless wokescold, but I don’t think it was my cancelly political correctness that kept the jokes from landing. I’m honestly not sure there were any jokes. It felt like someone … explaining a joke. Which is, I guess, the essence of comedy, if you think about it.

Rees glosses the individual terms in his book in a few sentences, in a few cases (the n-word, for instance — groaaaaaan) a page or two. To give you a sense of the definitions, here are the four types I noticed:

There are a few that just straightforwardly existed. People did sometimes say “logocentric”, and the inevitable “lookism” gets its own entry. A bunch of slurs show up, brought up in weirdly nostalgic tones — hilariously “queer” is one of them, Nigel Rees would be so pleased were he alive today!

There are a bunch that sound like jokes, even though Rees doesn’t acknowledge them as such. "PARENTALLY DISADVANTAGED: This is the preferred term for an [orphan]". It most certainly is not, and according to Google Books it almost certainly was not. It’s weird to fill a book with terms that you acknowledge are jokes, and then have others that seem like jokes, but you pretend they’re real.

There are terms that Rees coins himself: "PENILE IMPERIALISM: This concept hardly needs explaining. If no one has invented it yet, they should surely do so."

There are terms that are jokes that Rees heard about. Or more frequently read about. “A joke nonce-coinage in 'The Way of the World' column in The Daily Telegraph (2 December 1991) was 'quasi-autochthonous American Indigenes"??? What a knee-slapper. Thank you for repeating it.

Take the entry on “-challenged”. It’s an endless source of hilarity for anti-PC texts, so you might be interested in seeing what Rees does with it. Well, it’s really quite curious what he does with it:

One thing you realize rather quickly in going through these books: what life was like before Google. Rees had to have someone find an article that would use “physically challenged”, and he found it in Publishers Weekly. If that doesn’t give you a good enough sense of the danger emanating from “-challenged”, what about the acknowledgment that “actual .. coinages are now far out-numbered by jocular inventions.” I don’t know, Nigel, this kind of makes it sounds like this isn’t a real problem. It also makes it sound like you’re telling other people’s jokes! Anyway, here are other people’s jokes:

Two of these are apparently so side-splittingly hilarious that they get their own entries later in the book. (Did I mention the book is 157 pages long? That feels relevant here.) This is only half the list, but you get the idea: some of these are clearly one person’s comedy bit (“cerebro-genitally challenged”, for instance), others are part of a “what’s next?”-rhetoric — “constitutionally challenged” isn’t particularly funny, and likely not intended to be funny, it’s just a way of saying that this lexical construction is stupid. So where did Rees get all these examples? Well…

Yes, you read that right: his main source appears to be another anti-PC dictionary. I’m not going to track down these newspapers (the works cited for the whole book are two pages long and don’t provide any further details on these sources), but I’d bet that these two article likewise collect fanciful ideas of what a PC person might call someone who is old or fat or hard of hearing. There’s actually something rather fascinating about this author’s range of references. He draws on a variety of sources, but most references fall into three categories:

There are other books or articles that warn about the danger of PC — the famous Newsweek-cover story about the “Thought Police”, the New York story I mentioned at the beginning.

Other lists of supposed PC excesses — be those Beard & Cerf, or some jokey column.

The newspapers a person working in English media would subscribe to — The Times, The Independent, etc.

The book thus largely aggregates anti-PC anecdotes from other sources. The book came out in 1994, and Rees had clearly read a lot of the previous three or four years of “PC”-coverage. Most of his sources appear to be from 1991 and 1992. He doesn’t really seem to have delved much deeper than that, but when it comes to anti-“PC” tropes, he is extremely fluent. You get — as you often do in the early 1990s freakout over “PC” — a sense of a closed loop. Rees cites a few people, all of who agree with him. He doesn’t bother finding out why people (allegedly) speak the way he says they do. That slapdash incuriosity may well be the book’s covert moral: don’t bother to learn anything about these people and their ideas, he seems to be saying. Just pick up a few more dumb anecdotes from the Telegraph.

The dust jacket promises that “the author shows ... how compromise, unwillingness to offend, often coupled with festering resentment, is weakening and stifling the English language." It also speaks of an “enemy worming its way into our dictionaries.” The jokey pose of these books (such as it is) is supposed to telegraph a kind of heterodox attitude — these books collect absurdities that others are too stupid to notice.But in fact books like Rees’s are almost perfect encapsulations of a shared discourse — other people’s criticisms of the thing everyone hates, other people’s jokes about a thing everyone agrees is bullshit. As Rees himself admits: no one says the things he lists here, other than to joke about them.

Two things I noticed in this read-through that I think are also worth bearing in mind for the French books I’ll talk about in my next installment: There is the classic case of a kind of Newspeak redescription (this term for that term), which makes up the majority, though not the vast majority, of the entries in Rees’s book. But there’s another type of entry, though due to the sheer mass of inane fake synonyms it’s easy to miss. This is about terms (think “phallogocentrism” or “D.W.E.M.” [“dead white european man” for those of you not fluent in Fever Swamp]) where the rage is not about redescription at all — but about description tout court. The fact that this thing could be named as existing — and “this thing” almost always has to do with race, sexuality or gender — seems to set off Rees and the people he’s shamelessly cribbing from. This might be — that’s at least my hypothesis for now — why the “dictionary” became, for a brief time, such a potent vehicle for the anti-“PC” freakout. These aren’t really dictionaries (fully 10% of the book just append “challenged” to various adverbs, you can do this at home); the words collected in them mostly aren’t really words. What they are is a destruction of the idea of reference — it treats definitions the way a lot of anti-PC screeds treat socially salient anecdotes. Dinesh D’Souza, John Taylor and others see your anecdote about sexual harassment or a noose being found on campus and raise you some bullshit they either made up or seriously distorted. If we can’t have control of what anecdotes are significant, and what they mean, then we’ll take our toys and go home. A similar dynamic seems to me to play out in these dictionaries: if we can’t have the words, nobody can.

The other thing you notice in Rees’s book: While it’s definitely responding to actual changes in parlance (“African American” gets its inevitable entry), the book seems to be allergic to any language change around minorities, multicultural society or the empire — and I mean ever. Rees has a series of entries about the word “Indian” and various variations on the term — including one term that he (jokingly? perhaps?) suggests has declined in use since the 1760s! And he’s not kidding — here is that term according to Google Ngram viewer.

Ngrams have to be used with a great deal of caution, but I’m pretty sure it’s fair to say that this term (which I won’t repeat here) was on the decline long before the “politically correct” 1990s. If anything — and this is the point — the term may well have increased in use (though of course pretty marginally) thanks to all the anti-PC warriors putting them into their texts as a supposed example of what they were fighting against. This is the overall impression of a book like Rees’s — it’s an exercise in creative expression, just not a particularly original one. The whole format is there for Rees to say the words he really wants to say, to use slurs that had — by 1996 — become absurdly antiquated. As is so often the case when we read texts about the great silencings of the 1990s, the overwhelming impression is in fact the opposite: of a veritable discursive explosion.

[Given that this post has gone quite long, let me pause here. Next week, I’ll say more about the French dictionaries. Which are remarkable both where they follow their Anglo-American counterparts, and where they depart from them.]