Twelve Theses about Car Chases, Gender and History -- Part 1

I'm working on my book on cars and I may be losing my mind

[So as part of my effort to promote The Cancel Culture Panic, I’ve decided to talk about something completely different — cars! My conversation with Sarah Marshall and Alex Steed about Stephen King’s Christine is out now, and here is more stuff about cars from me!]

As part of my book on car culture, I have been watching a lot of movies about cars. And I started paying more attention to car chases — I’ve always liked them, but I’d never really thought about them as a historically specific filmic language. But it turns out they are. There are earlier car chases, but the wave of scenes we’re still riding really only started with 1968’s Bullitt. Car chase sequences thus accompanied a very specific period of our collective life with and around cars. Not the years when the Interstate Highway System was built, not the years of rapid suburbanization — but the years when the car began to effectuate the death of the American city. When calls for law and order and the control of a racialized other became paramount in American politics. And of course they’re also the years during which gender relations began the transformation they are still undergoing today — car chases, believe it or not, were part of that process, but more importantly of the backlash to that process. So that’s what these twelve theses are about: a cultural theory of the car chase sequence after Bullitt. Because Substack truncates posts after a certain size, and because I went a little crazy with screenshots, I’m presenting these twelve theses in two parts — the next part should be in your inbox in the coming days.

As all my current research into cars, this is still all quite new to me. I’ve been reading a lot, and watching a lot of movies. I’ve been going to court and the archives. I’ve been interviewing folks. But my ideas are still taking shape. So please feel free to argue with any and all of what I’m about to say! You can help make this book better — thank you for watching and reading along with me!

One: Car chases are sex scenes. Choreographed and stylized, their outcomes either irrelevant or starkly binary (Bullitt catches the guy/Bullitt does not catch the guy), they are — before any VW Beetles get smashed or water hydrants get knocked over — characterized by an excess of the most elemental factor of filmmaking: time. Here’s ten minutes of Nicholas Cage chasing Sean Connery, the bad guys of the movie are not part of this plot thread, the outcome is the one you saw in the trailers. None of the characters Cage and Connery interact with in the scene ever make a reappearance — at best they’re stock characters, at worst they’re stereotypes. It’s like a prolonged sex scene — you can get up, go to the kitchen, grab a soda, and still will be perfectly caught up on what’s happening on screen. Gratuitousness is the name of the game.

Two: Car chase scenes are largely homoerotic flirts communicated through (and hidden by) the medium of pure, unadulterated mayhem. That may sound a little strange, given that the people in the cars rarely interact. But they get to communicate their desires to each other in the most natural and intimate way possible: by grinding gears and grinding metal, by screeching their tires and shooting off their hubcaps. I’ll have more to say about this, but at base many car chase scenes are a shot/reverse shot dialogue between two or more people (“I’ve got you now!” “Oh, no!” “Cut him off!”), just with a bunch of shots of cars slamming into each other in between as buffer.

Three: Car chase scenes do not exclusively involve men, but they are nevertheless exercises in, or rehearsals of, masculinity. Visually, this is most readily apparent in the most common close-up used in car chases: what we might call the grim-face. A driver’s face scrunched into a determined mask, eyes squinting in a mix of panic and determination.

The chase sequence in The Rock I referenced above overdelivers on this score as well — at one point there’s no fewer than three men staring grimly past the camera barking things at each other, at passers-by, into a walkie-talkie (in one shot there’s TWO men in the shot scrunching out an imaginary windshield). The sequence is just crunching metal intercut with a truly absurd gallery of scrunched faces.

There are chases that don’t rely on this as much — H.B. Halicki’s 1974 indie actioner Gone in 60 Seconds, for instance, rarely looks inside the cars, and instead intersperses shots of a police commissioner, 911 operators, and media interviews with people (many of them women) witnessing the chase. Then there are the chases where only one driver is seen, for instance Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971) — in which, however, Dennis Weaver serves a downright astonishing amount of face.

It’s possible that this is a New Hollywood innovation. But this physiognomic aspect is certainly a dominant stylistic feature of the iconic 70s chases. A lot of those have a cop chasing after criminals, who have often enough just committed a major crime — it makes sense for Steve McQueen in Bullitt (1968), Gene Hackman in The French Connection (1971), Roy Scheider in The Seven-Ups (1973) to be pretty clenched when chasing after the bad guys.

Even William Petersen in William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in LA (1985), who is to my mind the most impassive driver in any classic car chase, gets a little grim-faced about halfway through…

Non-cops — think Barry Newman in Vanishing Point (1971) or Ryan O’Neill in Walter Hill’s 1978 thriller The Driver — tend to be more placid. But neither Newman nor O’Neill are shot frontally much at all, as Hill prefers to shoot him through the drivers’ side window and Vanishing Point’s director Richard A. Sarafian mostly stays outside of his vehicles. But Aykroyd and Belushi stay pretty inanimate for even the looniest parts of the final chase of The Blues Brothers (1980).

Four: Many classic car chases hate cities. Like Ford the iconic chase scenes of the late 60s and early 70s said to New York, LA, San Francisco, Philadelphia: drop dead. They delight in scattering civilians, making witnesses screm, destroying urban infrastructure. But it’s easy to miss that this hatred, as well as its object, are both gendered. The point of view implicitly inhabited and cinematically heightened in car chase scenes is that of a frustrated suburban driver who — unlike all these other clowns — has somewhere to go! These Odysseusses of the thruway experience everyone else as mere impediments, as cyclical and elemental — sometimes literally so, as in the case of Bullitt where Steve McQueen encounters the same green Volkswagen Beetle four times in wildly different locations, and where the Dodge Charger manages to lose more than four hub caps. The fantasy that many car chase sequences serve and service is that of the driver and breadwinner who no longer lives in, but drives in the inner city. Other chase sequences — think of the multi-car pile-ups of various Burt Reynolds films — have a more obviously suburban imaginary, where it’s not groups of nuns, or office drones, or hippies that are clogging the roads, but instead — shudder — just tons and tons of other cars.

The car chase plows a path of destruction through people just going about their business — shopping, heading to work, driving a bus. The driver in a chase adopts a pose of masculine hyperindividualism, everyone else gets cast as part of a collective. When they tear through cities, those cities are frequently peopled entirely by annoying stereotypes. “Are you aiming for these people?” Samuel L. Jackson’s character asks Bruce Willis’s John McClaine in John McTiernan’s Die Hard: With a Vengeance (1995) as the two race through Central Park in a cab. “No,” McClaine responds and then after a moment deadpans: “Well, maybe that mime.” Car chases love freaking out panicking pansies. And you sort of get the sense they think the pansies have it coming.

Part of the fascistic glee of these sequences is the implicit power to choose who lives and who dies — yes, who deserves to live and die. Of course, the driver doesn’t want to run over anyone, but gosh darn it if the situation doesn’t force him to run over someone! One of the most insane versions of this is the scene in Speed (1994), where the bus can’t stop for a woman pushing a stroller across the street. For one horrifying moment we’re left to contemplate the scenario where the bus has just run over baby while the child’s helpless mother is forced to watch. But then we learn — phew! — “there was no baby!” And the mother was no mother, but rather a homeless woman collecting cans. It really feels like the movie is toying with who ranks how highly as a possible victim, doesn’t it?

Five: When involved in car chase scenes, women drivers tend not to actually drive cars. Most frequently, they are passengers, especially prior to the 21st century. They sit next to James Bond, Smokey, or behind Short Round and, well, hold on to their potatoes. But when women are at the wheel, it’s very frequently behind the wheel of a bus or truck. Even in Hong Kong action cinema, miles ahead of Hollywood when it comes to women taking the wheel, women drivers most frequently drive trucks on one extreme and motorcycles on the other. In her entire action oeuvre, Michelle Yeoh appears to have largely been put behind the wheel of semis and on motorcycles. When she meets James Bond in Tomorrow Never Dies, she does take charge the way few Bond-girls previously had — but she does so on a motorbike.

Six: This is connected to another point: whether they drive trucks (Charlize Theron in Mad Max: Fury Road), busses (Sandra Bullock in Speed), or a car (Goldie Hawn in What’s Up Doc), women don’t drive alone. They have precious cargo they need to safeguard, or they have a (usually male) passenger who looks on in concern. Or they have Keanu Reeves looking over their shoulder. They may be running over road blocks, water hydrants, food carts while hurtling down city streets, but in some very literal sense they are responsible drivers – they are responsible for someone. And they are defensive drivers – far from nihilistically only wanting to make the other guy crash, they are defending someone or something.

But the fact that women tend to drive others has an aesthetic dimension as well: look at the still of Sandra Bullock and Keanu Reeves looking out the windshield of the bus in Speed. His face is all scrunched concern and determination, a proto-John Wick scowl. Her face is open, almost naive.

Now look at Barbra Streisand in What’s Up, Doc?: a very similar expression. The point here isn’t that this is a gendered pose (she’s a guileless driver, he knows to worry) – that wouldn’t be particularly surprising. The point is that it has to be: Hollywood doesn’t usually allow lead actresses to make the face I described above — Keanu can get away with it. This shot may well be the reason Hollywood doesn’t like to let women take the wheel. Because once they’ve done so you have to show them hunched over it, face contorted in a grim mask, murder in their eyes. So Hollywood splits their tasks: she gets to drive, but he has to reflect the affective stakes of the driving on his face, since she can’t possibly be allowed to do so.

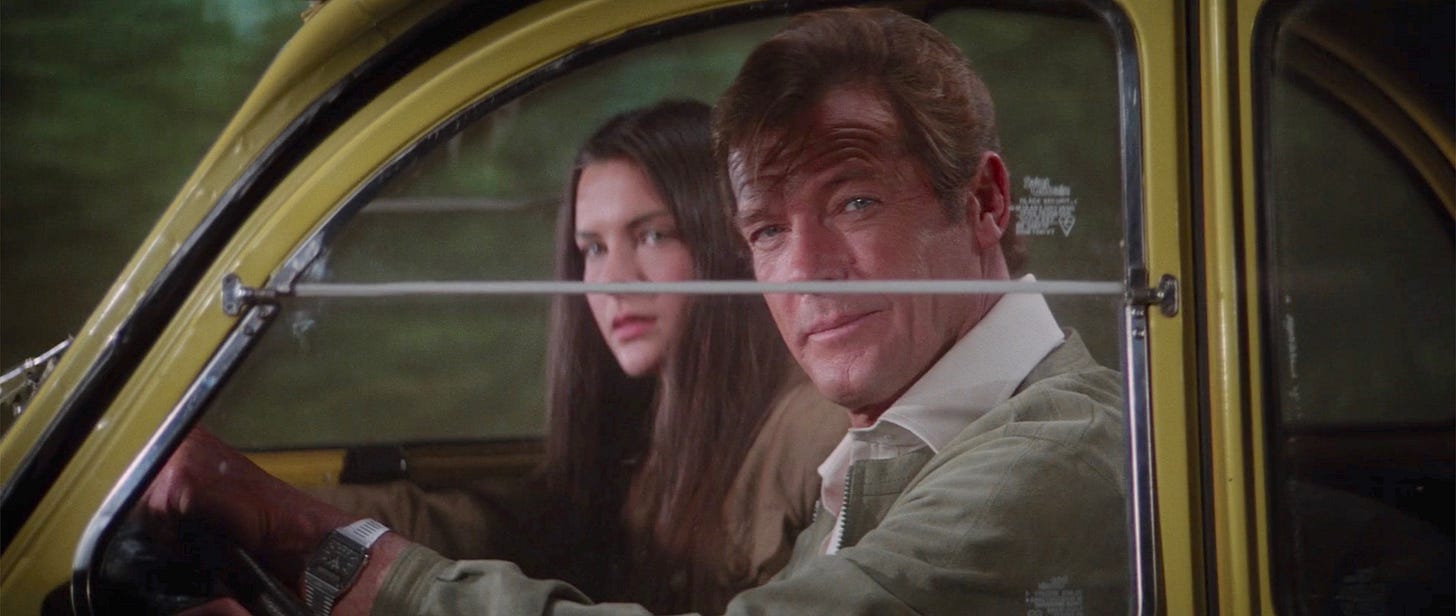

There’s a fascinating example of this dynamic in the 1981 James Bond film For Your Eyes Only. Bond and Melina Havelock are fleeing the compound of baddie Hector Gonzales in Corfu, with her driving her yellow Citroën 2CV. They’ve only just met, and as the film allows them to trade some information and get to know each other, she drives (with a placid, immobile, famous face, I might add — Havelock is being played by Carole Bouquet, the longtime face for Chanel No. 5).

Then the bad guys show up, the tires start screeching, the shooting starts. And they have to switch seats!

Stay tuned for Part II (and theses 7 through 12)!

Barbra Streisand, not Goldie Hawn.

For the flavor of real world car chases you might visit the Police Activity site on YouTube, where law enforcement officials pursue law breakers in high speed chases up and down freeways, rural roads, neighborhoods, parking lots, etc. The videos are from police car dash cams and the speeds and driving often terrifying.