On April 2, 1981, the film version Christiane F. — Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo arrived in German theaters. It would go on to become, as I mentioned, a massive hit, coming in at number 3 of the German box office, behind only Luke Skywalker (The Empire Strikes Back) and Disney (The Aristocats) for the year. Just as a literary scholar I can’t help but point to the gradual change in status of Christiane’s name: The book had Christiane on the cover as the ostensible author, though it was perfectly clear that the book was written by Kai Hermann and Horst Rieck. The movie makes her its title, and the book’s title its subtitle. She is no longer the story’s (filtered, possibly somewhat distorted) teller; she is an object, a protagonist in the hands of others.

The actual Christiane walked out of the film’s premiere. After that evening, at least for a time, Natja Brunkhorst became Christiane F. It was her who kept getting recognized and who eventually had to leave Berlin to get away from it. The two Christianes never met during filming; the producers thought it would rob Brunkhorst’s performance of its authenticity. They briefly met at a concert years later. “It was weird. We didn't really get along,” Brunkhorst said about it later. But perhaps it’s better to say: Christiane Felscherinow walked out. Christiane F.’s afterlife had begun in earnest.

The movie was among the first produced by Bernd Eichinger (1949-2011), who would go on to become Germany’s uber-producer. Eichinger loved adapting literary properties — among his next projects were Das Boot, The Neverending Story and The Name of the Rose. In most respect Christiane F. the movie is exactly that: a literary adaptation. It compresses the timeframe, streamlines the narrative, adds some OG book passages as voiceover. A lot of what made the book Wir Kinder so counterintuitive and haunting is missing from the film, and it’s largely replaced by vibes. I don’t necessarily mean that as a criticism, at least not of Christiane F. as a film. Because the vibes are tremendous. Director Uli Edel wrings a lot of detail from simple scenes and even single shots, and captures a set of particular Berlin moods.

It feels weird to say that a movie that’s fully 15% people shooting up, going through withdrawal or worse feels exhilarating. It doesn’t really. But before all the needles and jaundice, the film feels almost like a paean to the city that in 1981 most Germans likely held at least partially responsible for what happened to the real Christiane. Maybe it’s having been away from Berlin for almost 9 months, but there is something deeply thrilling about a movie that evokes the timeless feeling of a late-night ride on a Berlin U-Bahn past endless Neubauten while Bowie’s “V2 Schneider” (recorded at Hansa Studio 2 in Berlin a few years earlier) thrums on the soundtrack. Which muddles the film’s message somewhat, but probably strengthens the story: The film isn’t nearly as searching as the book in figuring out what draws Christiane to heroin (her father, whom Christiane clearly holds responsible in the book, doesn’t show up at all). But it kind of doesn’t have to. If you lived in this city and went to these parties and hung out in these half-space-y half-decrepit buildings, wouldn’t it make sense to try every drug?

All of that is before David Bowie has a cameo as himself, recreating the real-life performance at the Tempodrom, which the real-life Christiane Felscherinow attended. For a movie that on some level knows that its argument has to be that drugs aren’t cool, this movie has just real trouble not being cool.

The film’s Christiane is more of a cypher than the open-hearted, at times disarming narrator of the book. She seems to be newer to drugs by the time Kessi brings her to Sound, the disco where she first encounters her future junkie friends. Her first visit to “Europe’s most modern discotheque” finds the film at its most free from its source material: it’s not the best shot sequence of the film, but it’s the scene where the film gets to make visual points that the book doesn’t and probably can’t. There’s a shot where Christiane examines herself in a bathroom mirror…

… only to then immediately confront a future reflection of her — namely a junkie seemingly dead from an overdose — in one of the bathroom stalls.

Christiane runs outside to throw up, only to have the man in the toilet stall walk past her more or less okay. Their exchange of glances, and his sudden change in relative catatonia, feel almost comedic. She’s out of her depth at Sound for sure. But it’s also that categories of death and life don’t entirely apply in this subterranean limbo. The film underlines that theme by having the kids head to a movie theater inside the disco (I think the actual sound had a laser show, but no actual cinema, but maybe I’m wrong), which is showing George Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead (1968). In a bit of, ahem, ghoulish foreshadowing, the scene they watch is the film’s most horrifying scene of oedipal violence: 9 year-old Karen Cooper, zombified, attacking and killing her own mother. It’s really double foreshadowing: by the end of the film, Christiane will shamble through West Berlin pretty zombie-like; and while she may not succeed in killing her mother with her antics, she definitely gives off the right energy.

The other thing the Romero reference makes clear is that Edel did sort of think of his movie as a horror film. The horror of Christiane F. is: it’s a horror film where our heroine does all the things a horror film protagonist isn’t supposed to do knowing full well what will happen to her if she does. And does it anyway. Whether it’s investigating a strange noise in a toilet stall, whether it’s awful body horror, whether it’s having a car pull up behind you on the street at night: Christiane does the thing you’re not supposed to do, but there’s no shock, no jump scare in it. When that car door opens, she knows full well what she’s getting into.

Reviews for the movie were generally positive. Nevertheless, reviewers naturally used the hit movie based on a hit book from a few years back based on a massive panic from a few years before that, as an opportunity to reflect on what this cultural phenomenon said about the country. Why, they asked, are we being told this story at all? “What is this all for?” the reviewer for Der Spiegel harrumphed. “Drug education? Deterrence? Exploitation? Is this really an inside view of today’s youth culture — or is it more of a classic commercialized horror story, but dressed up in the latest punk duds?”

It’s noticeable that most of the reactions to both book and film were written by men. But by 1981, even male reviewers seemed to wonder about how much of this story was documentation and how much of it was exploitation. Recall that the book only came about because Hermann met Christiane at the trial of a West Berlin man who’d be convicted of sex with young girls. The book has remained relevant as a document of the heroin wave, but its success rested on the fact that it was also substantially about sex work. It also ran as part of a twelve-article series with some fairly voyeuristic pictures, albeit not of Christiane herself. Notice also that the film version traded heavily on the doe-eyed Natja Brunckhorst, a thirteen year-old whom the producers plucked off a Berlin schoolyard and cast as their child prostitute. In its original cut, the film includes a sex scene with (brief) nudity. Sure, the film dutifully spends way more time on vomit and blood than on the sex. But the question Der Spiegel was asking the film’s audience — "why exactly are you here?” — still seems relevant.

None of this is to say that it’s all about titillation and voyeurism. But it’s pretty clear that the drugs were, at least for part of the audience, a way to legitimate gawking at a young woman, to contemplate her body and what she did with it. Worry about drugs was always also a way to explain away sticking your nose in young peoples’ business. Or to not have to think too hard about why exactly you were sticking your nose in young peoples’ business. No wonder that the real Christiane Felscherinow — who had been able to sanitize her own story for Hermann and Rieck — walked out halfway through.

This point will be obvious to my German readers, at least German readers of a certain age, but it’s nevertheless worth making: it’s not that the Christiane F. reporting sexed up news coverage. Reporting on gender or changing gender roles on the one hand, and satisfying a certain (almost exclusively male) voyeurism on the other went absolutely hand in hand in late 70s/early 80s Germany. Here is a small smattering of covers of Der Spiegel about various issues (rape trials, generational conflict, venereal disease, dieting and Idi freaking Amin!) that nevertheless manage to smuggle in naked women offered clearly for a male gaze. They range from 1975 to 1981, so exactly the Christiane F. years.

Part of why I’m showing you covers of Der Spiegel rather than Der Stern (which would look different, but which participate in many of the same trends) is that Der Spiegel’s covers are easily and freely accessible on their website. But my point is simply that the idea that something could be news and the idea that something was titillating were not very distinct in this kind of presentation. So it’s not that the Christiane F. fixation was really about something else — for some people it surely was, but for others probably not. The issue is more that the voyeurism was impossible to divide out. A person who genuinely worried about hard drugs in schools, and who was weirdly obsessed with what fourteen year-olds did with, for and to one another, didn’t have to decide which side of that divide they came down on.

Just how entwined the impact of Christiane’s story and the fact of how crazy young she really was, becomes clear courtesy of an experiment from the fine folks at Amazon Prime (I am being sarcastic; cancel your subscription). That experiment is the juked up … remake? I guess? of the story as Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo from 2021. The series stars then-22 year old Jana McKinnon as Christiane, and the 9 years between her and Natja Brunkhorst make a surprising amount of difference. The show comes across as a story of hard-partying 20-somethings, with lots of colorful fantasy sequences. It’s basically impossible to tell when this story takes place (even though shooting in dingy passages in a Berlin U-Bahn station should be perfectly possible today, so long as you wait until the Le Crobag has closed.); it has lost its specificity with regard to time period. And it has lost something else, something that every frame of the 1981 film was suffused with: Jesus, are these kids young!

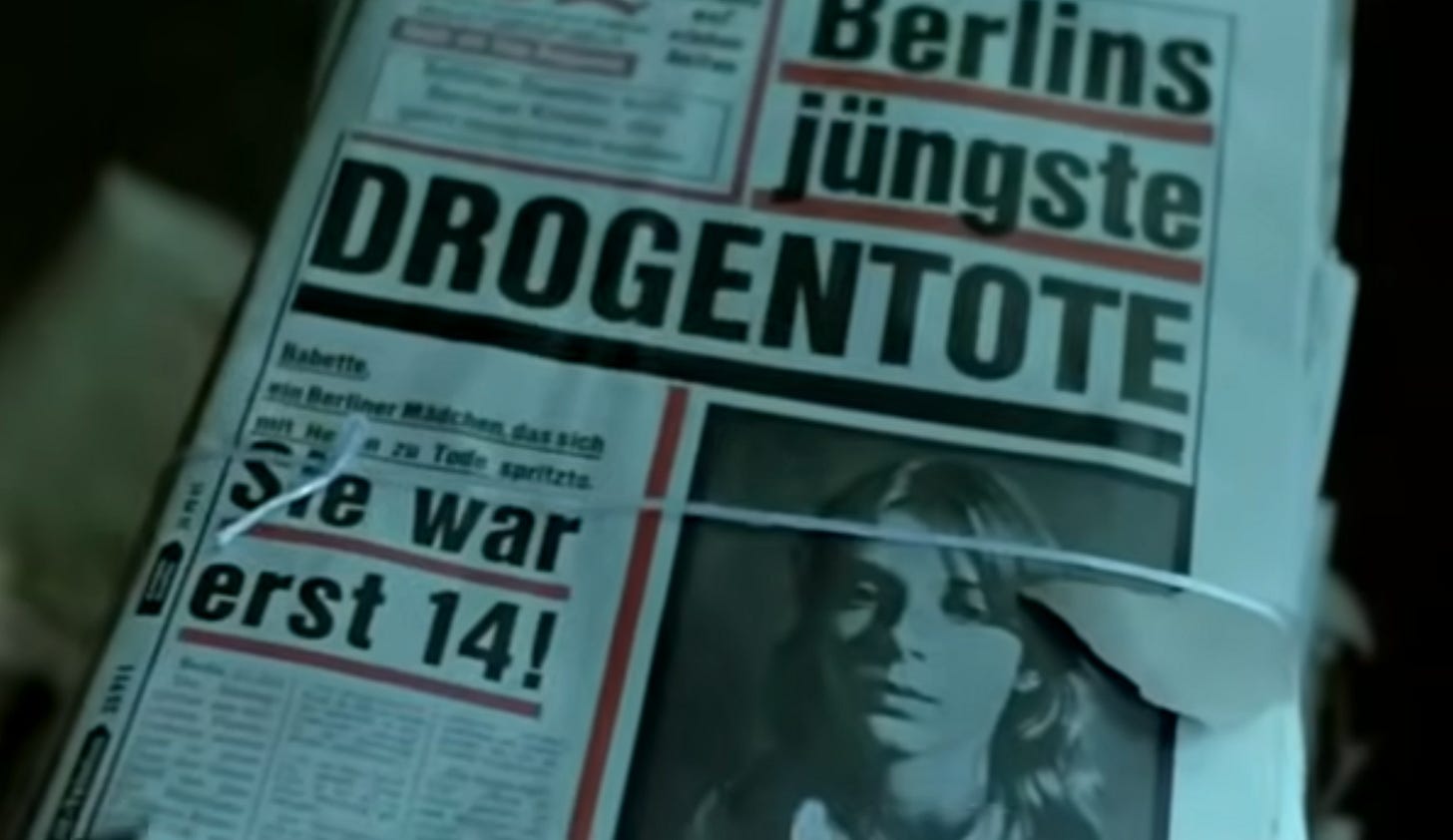

I don’t want to be too harsh on the new adaptation — though I’m still entirely confused as to what exactly it was trying to do —, but its ditherings and indecisions, its inability to pick what part of adolescence and what period in history this story is about seem to me linked. And they turn out to be illuminating with respect to the phenomenon that the miniseries attempts (and ultimately fails) to capture. One of the most indelible characters we meet in Wir Kinder the book is Babsi, who is played by Christiane Reichelt in the 1981 movie, and played by Lea Drinda in the 2021 version, where she’s given way more screen time and function almost as a coequal main character with Christiane. The reason she’s repeatedly mentioned in the book is that she was famous before anyone knew who Christiane F. was: Babette “Babsi” Döge was born in 1963 and was, when she died on July 19, 1977, Germany’s youngest overdose victim — her story so shocking it even made the New York Times. The cover reporting on her death is among the final things Christiane sees in Edel’s movie:

It’s the basic affective core of the entire heroin discourse in Germany. Drugs were experienced as an immensely affluent society eating its own young. But there were other places where this was starting to be true (youth unemployment, for instance). But in few of them were the young so young. When Der Spiegel reported on the growing drug problem all the way back in August 1970, they opened with the following story: “He started at the age of twelve, taking pills from his grandmother's medicine cabinet. At fifteen he traveled to Sweden and learned to smoke hashish. A year later, the student Mathias Gerson**, son of a teacher, was found dead in his room one morning — dead of an overdose of Polamidon. He was the first young drug-related death in the cathedral city of Cologne.”

I think that kind of youth has everything to do with the underpinnings of the Christiane F. phenomenon. It’s got to do with the unsettling voyeurism brought to bear on Christiane and her friends. But it also has to do with the fact that the politicization of the book always hit a wall: yes, for some portions of society, Christiane could seem like a verdict on student rebels; but Christiane and her friends were never stand-ins for those students rebels. Their rejection of society wasn’t political at all, at least not in ways the German public in the 1970s recognized, they were simply too young for that. In one article, Der Spiegel quotes an expert pointing out that drug-use had long been political — it was a pointed form of rebellion. With heroin, he says, the scene has become "de-ideologized." "Most drug addicts today are “nothing, not even students.” You can hear the ghosts of 1968 in that little aside. The do-nothings of the 1960s at least had the good sense to enroll in college; these kids couldn’t even hack that.

Of course, we might say that 13 year-olds are perfectly capable of political stances. The expert is probably not wrong to suggest that they are unlikely to be “ideological”. These weren’t little communists, reaching for a syringe and a rubber band, in order to really stick it to capitalist system. But I think the last 50 years, and much theorizing about kinship, intimacy and non-normative bodies have made us more alert that marginalized peoples’ improvised kinship systems may contain more politics than someone looking for another student movement or nascent political party might recognize.

Katheryn Bond Stockton’s The Queer Child points to the fact that what makes the child a “queer” figure, requiring control and sanction, is in part its ability to form attachments and intimacies unforeseen of and destructive to the (biological) families in which they first appeared. The children of the Zoo Station are queer in exactly that sense: they are children finding intimacy, kinship and a momentary abeyance of exploitation in a society that seems rife with bad intimacy, familial restriction, and exploitation.

Christiane moves on from alcohol to drugs partly because she wants to belong; and partly because she feels safer with junkies than with drinkers: junkies don’t take advantage of you when you’re passed out, they don’t beat you. When Christiane tries to kill herself by overdosing in a station toilet, she collapses onto two boys, “both around fifteen”, who just happen to be hanging out in a public toilet. Not for drug reasons, it turns out. For the other reason: “Satin jackets, crazy tight jeans. Two little homos. I was so relieved they were homos. They caught me, as soon as I came tumbling out of this toilet stall like a ghost. They immediately knew what was up.”

It’s a moment that seems to contain a whole universe of generosity and solidarity. It can make you tear up, and for once, in this incredibly grim book, with a certain warmth. There’s almost a kind of low utopians in the scene of these kids helping each other out in a public restroom in an U-Bahn stop in which, in a better world, they wouldn’t have to be. Certainly not utopian in the sense that everything is — pardon the pun — hunky dory. But it may be utopian in the sense of Bloch and Adorno: in showing us a better praxis, even in utter abjection, it holds up a mirror to reality, a glaring image of where that reality is wanting.

It’s probably no accident that the new series can’t capture that. Also probably no accident: among the many, many changes the new mini-series makes is Christiane’s home life. Domestic violence of the kind Christiane experienced is often understood as pre-political, but that understanding is itself political. Did the Christiane Felscherinow we meet in the book have an articulated politics in the sense that she had an opinion on who should win the next local election? Maybe not, but she had a sense of how power and violence were distributed in the world, and what was unfair about that distribution. My point in critiquing the Amazon-series is not to say “these actors are too old”; it’s to say: aging these actors up turns their challenge to their own society into a different one, and — most importantly — eclipses the one that the children of the Zoo Station, precisely in their status as children, seem to have embodied.