I feel like in the first installment, I kept talking around this book and its age. In this second part, I’ll likewise make another approach via geography, ideology and the history of affect. It’s not that I don’t want to tackle this book head-on, it’s just that it’s almost impossible to take Christiane’s story on its own terms. The last forty years have entangled her story with so many currents and counter-currents, it’s not only impossible to free her story from them. It’s that if you did, you’d ironically have very little left: the fact that this book exploded in the way that it did is part of what this book is.

As I explained last time, in talking about the phenomenon “Christiane F.” we’re talking about three things. About a person: Christiane Felscherinow, born 1962. And we’re talking about Christiane F., a media phenomenon. As I explained, the media phenomenon is not a complete distortion of what happened to Christiane Felscherinow. But it’s still important that the Christiane F. that the world meets is not the girl herself, but the girl as assembled by two journalists – Kai Hermann and Horst Rieck – in 1977. But even the version of the book that Hermann and Rieck assembled wasn’t what ended up getting published.Hermann and Rieck had real trouble placing this book anywhere. Eventually Stern, a big West German weekly magazine published the piece as a twelve part series, and eventually put out the book in its own imprint in fall of 1978. Then there’s the movie, directed by Uli Edel, which came out in 1981, and which again selects and reshapes the narratives. For one, the movie looks phenomenal, contains incredible songs by David Bowie, and is far more of a youth-picture than it is an anti-drug picture. The movie, which I’ll discuss separately, was a huge hit: released in April, it had 3 million tickets sold by the end of the year in Germany alone, making it Germany’s #3 movie of 1981 – behind The Empire Strikes Back and The Aristocats.

So, another approach. Let’s start in the place that’s in the title of Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo. The Zoo Station. If you’ve been to Berlin recently, maybe you’ve been there. But then again, maybe not. There was a time when it was the gateway to West Berlin, the place you’d arrive unless you arrived by air. Today it is what it was before Berlin was divided, a small station, busy but anything but cosmopolitan. It lies in the commercial center of West Berlin, next to (and indeed crossing) the Hardenbergstraße. If you haven’t been, the first thing you need to know is that it’s tiny. Frankfurt’s Hbf (Main Train Station) or Hamburg’s, which likewise both had drug and prostitution scenes in the 1980s, are absolutely immense by comparison. The Zoo was always fairly provincial.

And the station’s provincialism sort of stood in for Berlin’s. This was a half-city, improvised and unnatural; but also, as the writer Peter Schneider once noted, strangely at ease in its improvisations and unnatural rhythms of life. For about 10 years in the early 2000s, I lived on a street that had once been cut in half by the wall. I sometimes asked my elderly neighbors how they’d experienced this time, when they’d leave their front door and stare at a large concrete wall dividing two countries, two systems, and portending possible world war. One of them shrugged and said: we just used it to string up our wet laundry. If Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo ever mentions the wall, it’s just in passing.

A kind of preternatural stoicism has been part of Berlin’s self-identity for quite some time now. Helmut Lethen’s classic study of a kind of cool, detached almost cruel habitus during the Weimar years (published in English as Cool Conduct) takes a lot of its examples (Bertolt Brecht and Gottfried Benn, for instance) from Berlin. The kind of sangfroid that is so unsentimental as to be almost disturbing runs as a thread through Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo. The Christiane we meet in the book is never really mad at anyone, almost compulsive in her even-handedness: the vice cops? Pretty okay, when you get down to it. The teachers? Trying their best. The dealers? Generally decent. The johns? Mostly poor schmucks. The Church of Scientology? Actually okay people. This registers as just very … Berlin. A strange mix of extreme worldliness and provincialism — people who’ve basically seen everything but also don’t really leave their own particular district.

Built in 1882 as part of the elevated rail of the Stadtbahn, Bahnhof Zoologischer Garten was expanded to accommodate long distance trains for the 1936 Olympics. After the wall was built in 1961, it was the only long-distance train station fully in West Berlin (others were added later in Spandau and Wannsee). This in spite of the fact that it had only two tracks for long distance trains — just for comparison’s sake: Frankfurt’s main train station has something like 25. It emerged as a hot spot for prostitution, crime and drugs for a couple of reasons: it furnished one of West Berlin’s few connections to the outside; it had a street running directly underneath the elevated tracks; and it had a large 1950s style subway station right underneath, serving two major subway lines, the U2 and the U9.

In an interview Kai Hermann points out that the appearance of these kids at these locations was pretty sudden and kind of surprising to him. He was interested in why they were there, which led him to approach and interview Christiane Felscherinow. The Zoo station was also a place where Berlin had the kind of big city feeling that other cities at the time had a far easier time generating — owing to the fact that they were in fact actual cities with a center and a periphery and all that. So the Zoo station was, to some extent, also a place where West Berlin spectated and analyzed itself.

The Zoo station was a place at once of too much world and not enough of it. It was too international, too cosmopolitan, too worldly by half. But it was also tiny, cruddy and embarrassing. (In fact, Berlin managed to replay this exact dynamic with its recently-opened new airport: a colossus that in the end feels kind of small, and an international embarrassment that in the end isn’t even interesting enough by being properly disastrous.) The essayist Karl-Heinz Bohrer once wrote about West German provincialism that the real problem was that Germans were provincials who “slowly lost the wanderlust and yearning for an elsewhere that is really what being a province is all about, that sense that somewhere else would be somehow more sophisticated, richer, more modern, more important.” Germans instead had started “to mistake the up-jumped province for the urbane, the metropolis.” This was the Zoo Station: provincial without being cute, metropolitan without being impressive.

The point is: whatever Germans recognized in it, they disliked. And generally, we should say about this gateway into West Berlin: it was a gateway into a city it’s fair to say many Germans hated. I won’t say that that’s the only reason Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo became a bestseller, rather than a drug story about, say, the Frankfurt station, or the Platzspitz in Zürich. But a story about a young girl’s descent into hell set in Berlin definitely had that extra spice you needed to make a cultural observation of a particular subculture into a verdict on the city and an entire brand of politics.

When Berlin was the capital of Germany, it was, at best, an unloved capital. When Germany unified in the late 19th century, it was under the Prussian aegis, and not everyone was happy about it. In fact, any misgivings or disappointed hopes people had about the unification process, could be projected onto Prussia and, by extension, onto Berlin. Berlin was a truly modern city and soon celebrated and flaunted its modernity, which to some extent made it a metonymy for everything anti-modernist forces (of which Germany had a lot) hated. It was shaped by proletarian forces and their political movements far more strongly than Catholic Munich or mercantile Hamburg.

As one observer calimed in 1928, the area around the Gedächtniskirche (about a long block or two from the Zoo Station) was the antithesis of whatever was true of Germany outside of Berlin. “The German people is alien and superfluous here. To speak in the national language is to be nearly conspicuous. Pan-Europe, the Internationale, jazz, France and Piscator—those are the watchwords.” The observer, just to drive the point home, was Dr. Joseph Goebbels. But his optic, one that manages to discover in Berlin only whatever is opposed to “real” German national essence, has survived into the present day. “Kreuzberg isn’t Germany,” a speaker declared at the Gillamoos (a Bavarian carnival of sorts, I have no idea and no intention to find out): “The Gillamoos is Germany.” Kreuzberg is a district in Berlin with a lot of non-white Germans. The speaker was Friedrich Merz, who was elected German chancellor last weekend.

As I mentioned in the last installment, drug discourse in Germany was also always about “foreign” influences, and about “foreign” people. There’s the fact that German media could endlessly warn about foreign substances coming in from outside, while all the kids they were describing really got started on their drug journeys by taking drugs with which Germany was inundating the rest of the world. But there was also the matter of cultural influence: rock music, the US counterculture, etc. Christiane F. is also a story about the relationship between Germany and the anglosphere: Christiane’s junkie argot is shot through with anglicisms. From context clues you can gather that she would have pronounced “H” “aitch”; when she’s going through withdrawal, she calls it “turkey”; it’s about US influences, rock music, AlcAnon and later on Scientology! The book – which is based on the tapes, but was ultimately put together by two middle-aged German journalists – seems to sense in drug culture a first shockwave of an unwelcome de-provincialization, globalization.

So a kind of negative identification via Berlin (“we are whatever Berlin is not”) continued after the war. After 1945 both the various buildings designed by Albert Speer and the pervasive rubble became far more enduring reminders of the Nazi years and the Second World War than the fast-to-clean western cities would allow themselves. “I like Berlin for the ways in which it differs from Hamburg, Frankfurt, and Munich,” the writer Peter Schneider once wrote: “The leftover ruins in which man-high birches and shrubs have struck root; the bullet holes in the sand-gray, blistered facades; the faded ads, painted on fire walls, which bear witness to cigarette brands that have long ceased to exist.”

Starting in 1948, just to make matters worse, the eastern half of the city became the capital of another country, the German Democratic Republic. As Christopher Clark has pointed out, as the Western Allies began rebuilding their parts of the country, they offered the population there a narrative where Prussia, centered around Berlin, had been the problem with Germany all along. It’s not a mystery why Germans living in Hamburg, Frankfurt and Munich went along with this narrative: it located Nazism outside of their own borders, and implicitly made it the GDR’s problem. In any event, if Berlin became a symbol of postwar Germany at all, it was a negative one — broken, incomplete, both its crimes and punishments spectacularly out in the open, it embodied everything West Germany didn’t want to see about itself.

In the last installment of this essay I talked about drug abuse as the dark unconscious of West German postwar affluence. As the Schneider-quote suggests, Berlin had a funny role to play in that affluence. Everyone was getting richer. But Berlin didn’t really fully partake, or at least not partake on equal footing. After the war many of the famous industrial manufacturers headquartered in the GDR relocated to the West, industrializing previously rural areas. This very much included Berlin — the encircled city was just too risky a location for strategically important production facilities, and too far from the markets the companies were actually manufacturing for. As a result West German postwar wealth was made in places like Bavaria and the Ruhr area … and if anything it was drained towards Berlin. Berlin, or the three-quarters of the city West Germany controlled, was kept afloat, and indeed populated, by subsidies. This attracted populations that were unusually dependent on subsidies — cheap places to live, for instance, transit subsidies. When Germans looked towards Berlin, they saw a bunch of moochers.

By 1976, they had another reason to look down on Berlin: the city was associated more than anything with the German counter-culture. The lack of a draft had driven a lot of more alternative-minded young Germans to the island half of the “Siamese City”, as Peter Schneider calls it. Berlin wasn’t absolutely ground zero for left wing organizing at the time — Frankfurt, with the School for Social Research and its active squatter scene might have been able to compete for that title. But many of the central attention-grabbing events of what in Germany has become know by the metonymy “68” took place in Berlin.

It’s worth emphasizing again, as I did in the last installment, that the Felscherinow family appears to have been swept up in exactly none of this. But reading a story of a girl gone wild in mid-70s Berlin while you’re living in, say, Dormagen in 1978, the connection between the atmosphere created by these events and the world Christiane inhabits would have been as clear as it would have been illusory.

As Anna von der Goltz explores in her The Other ‘68ers, the mythification of the SDS left tended to tell a story about radical activism — from promise to disappointment, more or less. When the story more realistically is about simultaneity: yes, more young people were joining communes, protesting the Vietnam war, etc. But the vast majority of course were doing different things entirely. They went with the times, but they combined a few select countercultural signifiers with different forms of conservatism. Still, whenever this generation was analyzed after the fact, analysis tended to act as though the student radicals had exemplified the generational experience. This — and that’s my point here — made 16 year old Christiane F., who was not a child of 1968 a metaphorical child of 1968. This is what I meant by distinguishing the biography of the person from the narrative that grows up around her: these two aren’t that distinct in what happened; but the Christiane F. we meet in the late 70s is made to mean something that seems quite distinct from the experience Christiane Felscherinow lived through in the early part of that decade.

1967 brought to prominence the Kommune 1, a commune located in various apartments on loan from young German writers and intellectuals. The Kommune 1 was designed to destroy the institution of the nuclear family, which the communards regarded as the smallest institution of the repressive state apparatus and the incubator for fascism. The Felscherinow family was at the same time living in Nützen, a small town just north of Hamburg. Christiane [quote]. In the late 60s, many politicized young people came to Berlin. The Felscherinow family did not: they arrived in Berlin in 1968 hoping, as Christiane will put it in Mein Zweites Leben, “to parlay government subsidies into opening up a marriage brokerage.” I think it’s worth dwelling on that disconnect: Christiane would one day be regarded as something of a verdict on the libertinism of people like Rainer Langhans and his fellow denizens of the Kommune 1. But in fact, she grew up in a very traditional — too traditional — nuclear family, one whose business it is to … create more nuclear families.

As I noted last time, one place where the book seems to just straight-up agree with its young protagonist is the question of domestic, sexual and gendered violence. The authors don’t seem massively interested in it, but Christiane seems to bring it back up again and again — the way she seems to regard society is just familial violence radiating outwards, through the corridors of the apartment buildings, through the workplaces and schools, and then through the broader culture. There’s a super dark throughline that suggests that junkies are ultimately a better hang than drinkers: drinkers get violent, junkies just kind of shrink into themselves. Drinkers use stupor to take advantage of women, junkies are respectful. The drug scene Christiane describes has way less violence than her home. It’s still noticeable that the way the book was metabolized was basically that it was all her mother’s fault for finding fulfillment outside of the home and not “paying enough attention”.

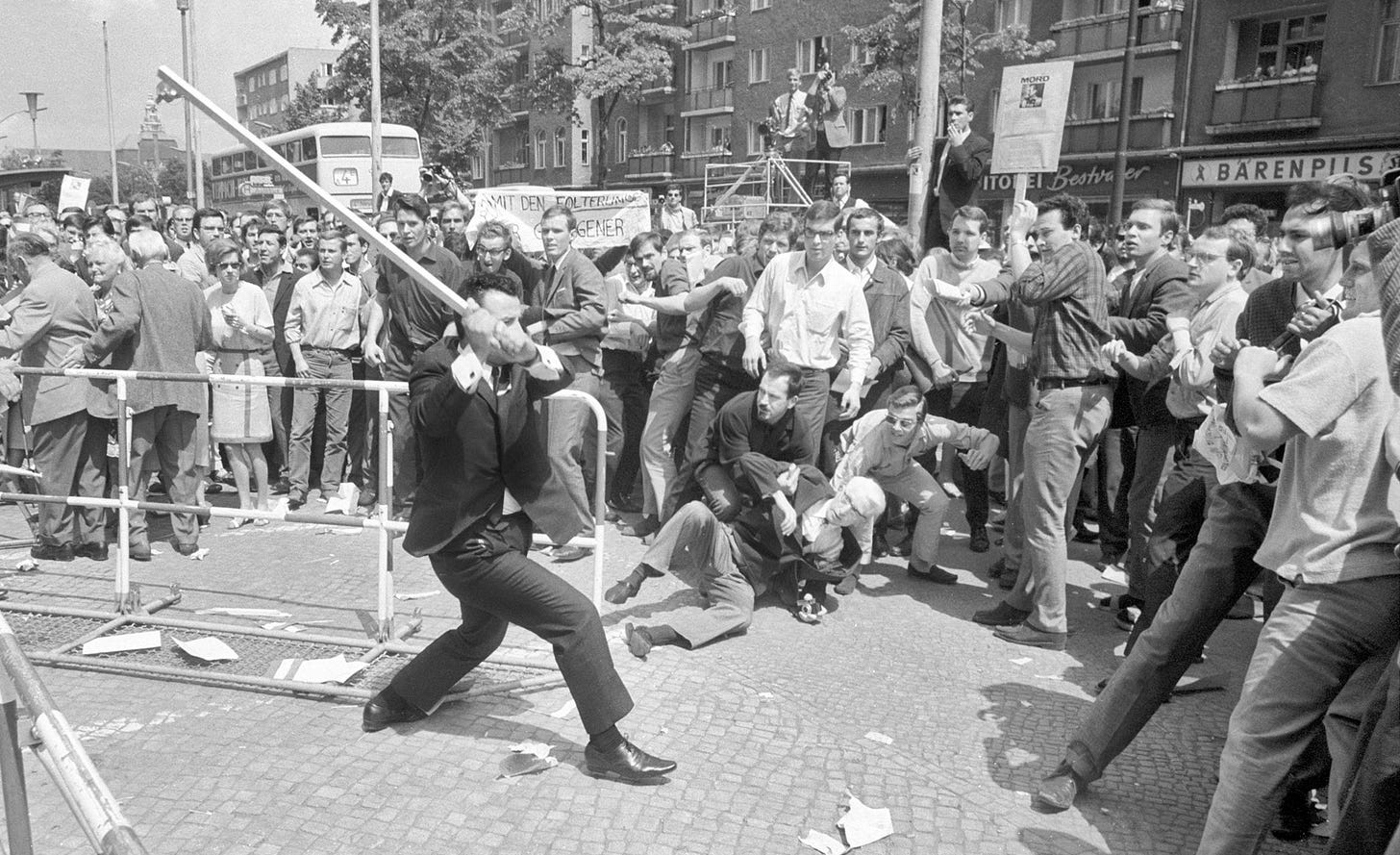

On June 2, 1967, the Deutsche Oper in Charlottenburg played host to massive protests against the Shah of Persia. After the Berlin police, aided by the Shah’s own secret police, began beating up on protestors, street fighting broke out — a policeman, Karl-Heinz Kurras, murdered the student Benno Ohnesorg, while the latter was running away. The next day, Axel Springer’s right wing daily BILD, headquartered by the wall in Kreuzberg, titled: “This is Terror”. They were not referring to the police. The paper claimed Ohnesorg, victim of the Berlin police, was instead “the victim of riots staged by political hooligans." "The hubbub was no longer enough for them,” the paper wrote about people who had gotten beaten up by their own police, and by the secret police of an authoritarian dictatorship with no jurisdiction on German soil. “They need to see blood." The Felscherinows were still living in northern Germany at the time. Still, there’s one first tenuous foreshadowing of Christiane’s later fame in the Ohnesorg affair: the idea that cracking down on Berliners with furious state violence and that you could sell that violence as justified and in fact their own fault was an early stirring of the politics of repression in which Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo would later (and despite its best efforts) get entangled.

Because Wir Kinder is to some extent a book about authority, and about how it is good. In the chapters narrated by Christiane’s mom and representatives of the criminal justice system, there is a clear narrative of too much permissiveness. Christiane seems far more nuanced in her assessment, pointing out that a lot of her rebellion had to do with unjustified, cruel and random authority. Mein Zweites Leben even offers a reading of the dynamics of Wir Kinder that suggests that identification with authority might have been Christiane’s problem: Christiane’s tragedy, the author writes in hindsight, is “that her empathy seals her fate, since she tries to understand rather than hate her abusive father.” Wir Kinder, likewise, emphasizes that Christiane has the run of Berlin the way she does not due to parental lassitude, but primarily due to lack of resources: her mother has to work — as it happens at the Axel Springer publishing house.

Christiane’s portrait of her father is fairly devastating, he objected to it upon publication. She speaks with palpable disdain of “my father’s plans”, and none of them appear to be those of a radical. They are stultifying in their conventionality, and his daughter, although just a teenager, senses that only too well. “I didn’t have any idea what was going on with my dad, and why he flew off the handle at every little thing. It only dawned on me later […]. He had big ambitions and every time he tried to make good on them he’d fall back on his ass. His dad despised him for it.[…] My Opa had always had big plans for my dad. The family was supposed to be somebody again, like it used to, before the communists seized all their properties.”

We first meet Klaus-Dieter Felscherinow unemployed, but waxing his Porsche, out drinking with younger men when he’s not beating his kids. At several points her father reappears in her life with various tough-love schemes that he’s far too diffident to pull off, and that usually end up just darkly comedic. While locked in her room, Christiane begins selling her used underwear off the balcony. In the late 70s he is “on a total Thailand-trip”, “of course mostly because of the chicks, but also because of the cheap clothes you could buy there. He saved all his money for his Thailand-trips, that was his drug.” This isn’t the portrait of an over-permissive hippie, in other words. Christiane (or her interlocutors) understand him as a petit bourgeois whose ambitions are too big for his britches.

One of the more heartbreaking motifs in Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo is that his daughter more or less thinks she’s accidentally imitated him. Drugs are a way to be less ordinary, drugs are a way to rise up in the world — not in terms of economics, but in terms of an economy of cool. Drugs allow her to feel better than others, a desire Christiane heavily implies she copies from her parents.

Recall the passage I quoted in the last installment: Christiane in the U-Bahn being making fun of the “squares”. Or think of the way she seems to be kind of elitist about “advancing” through the ranks of various drug cultures. She clearly relishes the junkie cant, which merges in an interesting way with the Berlin penchant for nicknaming (Berliners love giving famous locales nicknames, and the junkies have an entire cognitive map of their own — the Bonnhoefer Institute where they do their detox, for instance, is known as “Bonnie’s Ranch”). There’s a kind of low gnosis here. She thinks her johns are “jealous” of her, pities their normalcy. On the other hand, as she hits rock bottom, the book really plays up the idea that she’s desperate for the kind of normalcy she once disdained. The point is: this is a story about a social climber who, like her dad, falls on her ass.

On April 11, 1968, Neo-Nazi Josef Bachmann opened fire on student leader Rudi Dutschke on the Kurfürstendamm. Dutschke, struck by three bullets, survived, but never fully recovered, eventually dying in 1979. In reaction, protestors burned the daily edition of BILD, the paper having launched a massive campaign against the student leader in the months leading up to his assassination. This was the summer the Felscherinows packed up their possessions and relocated to Paul-Lincke-Ufer, maybe 2 miles from the BILD headquarters. Kreuzberg, and specifically SO 36, where the Paul-Lincke-Ufer is located, became associated with communal living, left-wing organizing, and autonomous Marxist squatter collectives, most of that happened in the 1970s and 1980s.

Meaning: when Christiane’s family moved there, the center of radical organizing was in the West of West Berlin, basically within reasonable commuting distance to the Freie Universität. SO 36, hemmed in on three sides by the Berlin Wall, was marginal in that story. Christiane’s mother Ursula worked in the building in which the media campaigns against the student rebels were coordinated. Still, the family story, which really could not have been more conventional and, by Christiane’s own value system, “square” (spießerhaft) would eventually come to be identified with alternative lifestyles the area would later become identified with. After all, Kreuzberg would not always remain marginal to the left. By the time Christiane told her story, and by the time her story was assigned to generations of German schoolchildren, the associations between Kreuzberg and left-wing organizing would have been obvious and natural.

On May 14, 1970 in Berlin-Dahlem, Gudrun Ensslin and five others sprang Andreas Baader from police custody. Baader was in jail for firebombing two department stores in Frankfurt. It was the birth of the Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF), which would conduct a massive terror campaign across West Germany for the next 25 years. In November of 1973, a new terrorist group, the Revolutionäre Zelle (RZ) began its bombing campaign in Berlin. The Felscherinow family had left Kreuzberg by this time: “Excitement was followed by disappointment, the business plan didn’t work out,” Felscherinow summarizes in Mein Zweites Leben. Her parents move, as mentioned, into the Gropiusstadt, a new high rise development that had broken ground in 1962. It’s about as far from the beating heart of things as you can get.

As a guy currently writing a book about car culture, it struck me how much people drive in Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo. Christiane’s parents do, her dad is obsessed with his Porsche. But of course so do her eventual johns. Berlin drivers are like New York drivers: they exist, of course, they are even plentiful. But they are a separate species, their experience of Berlin an entirely different one from the vast majority. This was even more pronounced in the early 1970s: what’s the point of a car if you can’t drive more than 10 miles without having to pass a (pretty onerous) inspection at a border check point? If the closest cute small town, the closest campground, the closest gothic cathedral is not only in another country, but in an enemy country? It reminds me of the China Miéville novel The City and the City: there were several different cities co-occupying the physical space people called Berlin. Christiane grew up in one, and what people saw in her story happened in an entirely different one.

We could say that these two Berlins finally become one in April 1976. Christiane attends a concert by David Bowie near the Anhalter Bahnhof, and does heroin for the first time. "That was on April 18, 1976, a month before my 14th birthday. I will never forget the date." There are three things that I think are important to take away from all this:

(1) The German reading public’s relationship to Berlin was absolutely overdetermined by the time Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo arrived in 1978. In engaging with the story of Christiane F., the public was grappling with a bunch of national traumas, national neuroses, and political currents and counter-currents, none of which the real Christiane had really been embroiled in during her descent into addiction and prostitution. Furthermore, the zoo station and Berlin did important work: this was a Berlin story, and about Germany’s increasingly vexed relationship to its capital and — more importantly — what it represented.

(2) There is a tendency in German media to interpret anything and everything that happened after 1968 as a verdict on 1968. I can’t tell exactly when exactly this started, but Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo is certainly at the beginning of that process. This impulse has become more and more identifiable as a weird and ahistoric compulsion in recent years, where you get people blaming phenomena on “the 68ers” that involve people who were negative 20 years old in 1968. This is, in other words, an irritable gesture seeking to resemble a historical narrative. There’s a great essay by the writer Till Raether about re-reading Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo forty years later. He describes how the way parents talked about Christiane F. clearly had to do with a kind of reaction to leftism: By the time he picked up the book in the late 70s, “the everyday discourse in the Federal Republic and West Berlin,” he notes, “had seamlessly transitioned from ‘but the terrorists’ to ‘but the drugs’.”

(3) It’s important to emphasize that Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo both is and is not a part of that backlash. It’s pretty clear the authors (and I’m including Christiane herself among them for a the moment) were very much trying to avoid having it be that. The whole point of Christiane’s narrative was that simplistic narratives of the drug problem were misleading. “It wasn't like I, poor girl, was deliberately hooked by a bad addict or dealer, as you always read in the newspapers,” the book says." “I don't know anyone who was hooked against their will. Most young people come to H on their own when they are ready, as I was."

That last sentence is, I think, revealing: Christiane is always so confident in her own self-assessments, but the book has a heartbreaking way of signaling that clearly she’s often terribly wrong in them. But the thing is: the book in a subtle but pretty effective way undercuts all the other people who are supposed to know what’s happening to and with Christiane. As I mentioned last time, the chapters written by her mother are so by-the-numbers, you can’t tell whether her mother is just a deeply incurious person or whether the authors just really hang her out to dry. The overall effect is that Christiane is wrong about herself, but so is everyone else. This extends to the political dimensions of the story as well.

In general, and especially when it lets Christiane do the talking, Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo is very explicit that a crackdown won’t work. When it comes to what Christiane would have wanted, it’s about a reassertion of authority, as I said, but really about parental authority. It largely refuses to villainize just about anyone — every junkie, club kid, even dealer in it tells Christiane not to do drugs. Christiane’s empathy, too, feels almost toxic: she won’t blame the dealers, the johns, the cops, anyone really. She’s truly unremitting only when judging herself and her immediate family.

It’s significant in this context that the book doesn’t really follow a descent into hell narrative: in some of these 70s books you get from smoking a joint to shooting up heroin in like a chapter. I think that kind of fatalism exists in books like this because it licenses intervention: if only we had done x after we caught her with a joint, perhaps she wouldn’t have run off with the carnies! If only we had cut her out of our will after she pawned our fine china, etc. etc.! Christiane F does have this narrative logic at moments, though Christiane explains why: she thought of it as advancing, at getting admitted to more and more secret layers of “the scene”, i.e. the drug world. She’s basically really getting into a hobby, just that that hobby unfortunately is injecting herself with heroin. But it also has things very out of sequence: there’s a moment late in the book where she steals money from her mom’s wallet — which she presents as really hitting rock bottom. Thing is, she has been prostituting herself for like a hundred pages at this point and had sex in front of people at an orgy like 10 pages before!

It’s clear that in their selection Hermann and Rieck play up these counter-intuitive moments, and I suspect it’s because they want to ward off a kind of simplistic if/then-logic. They understand that the book will be read as a call for restoration of specific forms of authority. And they seem to understand that Christiane’s story in truth is nothing of the kind. Part of this is probably that they had been in Berlin for the entire period I described above. They knew that, if the books was a hit, how it would be metabolized. What questions it would be used to ask. And what questions it would be used to ignore. In part III, I’ll talk a little bit about the afterlife of Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo: if today’s installment was about how the book almost necessarily was read as a final verdict on the 1960s, the next one will be about how the book became the starting gun of the 1980s.

![Kommune 1: Rainer Langhans spricht über die Kult-WG - [GEO] Kommune 1: Rainer Langhans spricht über die Kult-WG - [GEO]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WLwy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcd5c1b5a-d501-4636-8b74-ca6818a07d42_2048x1365.jpeg)