Service Post: Scary Elections in Germany Explained to Non-German Readers

On the Saxony and Thuringia elections

For a long time, German elections weren’t exactly something people outside Germany had to pull their hair out over, but those days are clearly behind us. The results of last June’s European election in Germany were scary enough that US commentators (and US-based readers of this newsletter) took note. And now it’s Saxony’s and Thuringia’s turn. The two Länder in the formerly communist east of the country both charted a fairly unique course post-unification. And they have now delivered pretty horrendous news. In this post, I will focus on Thuringia. But the results in Saxony are equally scary, if more complicated.

Saxony has long been a deeply conservative state. The CDU has been in power pretty much continuously since unification, although it’s had to enter coalition governments overt time. The CDU’s main competition has not come from the left (including Die Linke, which was never particularly strong in the state), but from the AfD. Die Linke’s best result in the state came in the 2004 state election, at 23 percent (the CDU got 41 percent of the vote). The CDU’s position has steadily eroded (from a staggering 58 percent in the 1994 election to 32 percent in 2019), even before the AfD entered the fray in the 2014 election. Yesterday, the AfD won 31 percent of the votes, gaining about 3 percentage points, the CDU held just about even at 32 percent.

Thuringia meanwhile was unique in that its governor, Bodo Ramelow, came from the postcommunists of Die Linke, the first and only time this has happened in post-unification Germany. Die Linke’s rise started in the late 1990s — but the party posted its best results yet in 2019 (the last election) with 31%. Those are “popular party” (Volkspartei) numbers in Germany — only the CDU and the SPD tend to get them. This spectacular rise was paralleled by an early collapse of the CDU and the SPD. The AfD did well here in the last two elections — especially in the southeast of the state.

I will walk you through the shift in yesterday’s election as best I can with limited space. And I’ll gesture to some reasons and consequences. What I won’t give you is a big spiel about East Germany, the legacy of communism, disinvestment, etc. It is certainly true that election results like these would be highly unlikely in one of the Western Länder, at least for now. But I am (1) about as “Wessi” as they come (other than living in Berlin, my entire life in Germany was spent within biking distance of the country’s western border), and you really don’t need me to tell you about East Germans. And more importantly, I am (2) not so sure how much this is an East German story, other than in magnitude.

The shift seems to me a German one, not a Saxon or Thuringian one. Bodo Ramelow remains a popular governor. And yet, as you’ll see, his voters abandoned him in staggering numbers. That suggests that national concerns drove these voters, not local ones. And that is an important, and deeply troubling, shift in German party politics, not in East German party politics. These same states — Thuringia and Saxony — used to be basically one-party fiefdoms held together by powerful governors (Bernhard Vogel/Dieter Althaus in Thuringia and Kurt Biedenkopf in Saxony). People would remain loyal to their governor even if they were otherwise abandoning the party he represented. That is clearly no longer the case. So let others explain the locally specific developments that shaped these results — and, to be clear, they exist. I want to highlight these results as the canary in the coal mine. (I should say that my sense of this process is partly shaped by Thomas Biebricher’s excellent study of the erosion of “center right” parties in Europe — which unfortunately does not seem to exist in English yet.)

So… where to start. Let me just show you the election results in Thuringia.

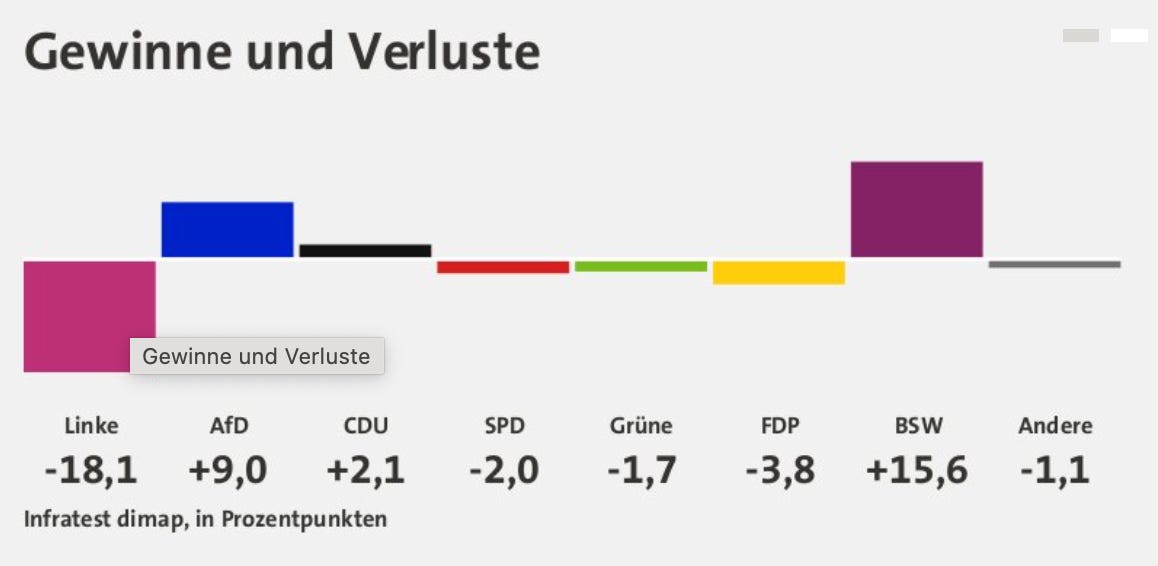

The AfD will easily hold the largest number of seats in the new Thuringian parliament. As of my writing this, it’s looking like 31 or 32 out of 88. Here are the changes vis-a-vis the previous state election (which already ushered in a bit of a constitutional crisis, something I’ll talk about below).

You’ll notice Die Linke under governor Ramelow absolutely collapsing, its support just about halving. The CDU and AfD gained significantly, the CDU far more modestly than the AfD. The numbers if anything oversell the CDU’s success: the CDU lost a ton of votes in the previous election (2019), about 12 percent. They had nowhere to go but up. The AfD is now easily the biggest party. The AfD is the strongest party in most voting districts in the state — in one, Saale-Orla Kreis I, the party got 40 percent of the vote, its direct candidate 47 percent. But by American standards, the city/rural divide is fairly attenuated — there are no 80% AfD districts, but there are also few where they were effectively shut out.

The CDU over the last few months (and certainly since the terror attack in Solingen on August 23) has been trying to run an AfD-lite campaign, largely playing on the AfD’s turf (immigration, asylum seekers, culture war, rolling back climate legislation) and trying to offer an alternative to voters drawn to the AfD’s core issues. I’m sure there’s a lot of analysis to be done yet, but shockingly this … does not appear to have worked. The gains for the CDU have been absolutely minimal, and the gains for the AfD in Thuringia at least explosive. Which is great, given that a bunch of other parties (including Chancellor Scholz’s SPD) seem to have decided to go in on the same losing strategy. Almost everyone in Germany these days, wants to offer fascism-methadone to possible AfD voters, but people prefer, it turns out, the genuine article. As for the people who are in no danger of voting for fascists? Less and less in politics seems to be done with them in mind…

Speaking of Chancellor Scholz: The parties represented in the federal government in Berlin — the “traffic light” parties SPD, Greens and FDP together barely cracked 10% in Thuringia. Note that German election have a 5% cut off, meaning unless a party wins a seat directly (i.e. their candidate gets the most votes), they won’t be in parliament at all if they get below 5% of the vote. If these numbers hold, this would be the case for two out of three of the ruling parties. The Thuringian numbers, I should note, are particularly bad — if an election were held in Brandenburg today, for instance, the three parties would garner 30%, if polls are to be believed. But they’ll exert a force of their own. Whatever normalization of far right positions has occurred so far, it will pale in comparison to what comes now. Either everyone will chase the AfD’s voters by any means necessary, or they will seek to govern with the AfD. Supposedly this is not in the cards, but it’s hard to imagine that “firewall” holding much longer (in fact, Thuringia is where that “firewall” was first cracked, more on that below).

So the strongest party in Thuringia is a party that Germany’s constitutional protection service has under observation for right-wing extremism, run by Björn Höcke, a man you are legally allowed to call a Nazi. That doesn’t mean that Höcke will be governor of Thuringia. There are other possible coalition that could keep the AfD out of government, but they are beyond awkward. Thuringia is headed for a situation like in France or Austria, where the ascent of the Far Right forces more and more mismatched compromises of centrist and left-of-center parties to keep it out of power — which only softens the contours of the governing parties and sharpens those of the Far Right. If I don’t sound very sanguine about that process, it’s because it never ends well.

The other party that made out like bandits is the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) a new party launched by a defector from Die Linke named — wait for it — Sahra Wagenknecht. This is the young party’s first state election, and it had a pretty impressive premiere. Of course, the main trick they seem to have pulled off is making sure that Die Linke lost about half its votes and lost the governor’s office. This is in keeping with Wagenknecht’s overall persona, who seems to think of herself as the scourge of the capitalist class, but has largely proven the scourge of fellow leftists.

How left is her new party, the BSW? A lot of ink has been spilled about this in recent months. As sociologist Oliver Nachtwey has put it, “Wagenknecht’s approach, which she refers to as “left conservatism,” “blends social conservatism with economic progressivism.” And “its common thread is an opposition to left liberalism”. It’s clear the party is more conservative on cultural issues than Die Linke; Wagenknecht herself seems to be cribbing from ordoliberal and nationalist playbooks that haven’t been part of a leftist vocabulary for a long time; her main target are “lifestyle leftists”, which basically has meant importing a kind of anti-woke resentment politics. Wagenknecht’s idea of “average”, “hard-working”, “working class” German is — and she barely bothers to make any bones about this — white. What she would do for these people is unclear. But she can offer herself as a channel for their outrage.

There’s a reading that says that the party is a kind of left authoritarian equivalent of the AfD. On the other hand, the party’s pro-Putin course seems to place it on the far left, while its national nostalgia … sort of doesn’t. Maybe the Cinque Stelle in Italy are a good analogy. In any event, as Stefan Reinecke put it in the taz recently, the rise of Wagenknecht herself seems like an indicator of an “Italianization of the German party system”: “The two main pillars, the CDU/CSU and SPD, are slowly losing their central position. Situational merchants of outrage like Wagenknecht are on the rise. The East, with its loose party ties, is a trendsetter.” Wagenknecht herself is basically a less funny Beppe Grillo. More importantly, I think, Reinecke is right to suggest that the BSW doesn’t matter for how it ties to Germany’s political past, but as a harbinger of its future. It may not have staying power, but it heralds the arrival of wave after wave of populist or pseudo-populist movement parties — parties that, as a rule, direct most of their ire leftward or towards populations supposedly championed by the left; and parties that, again as a rule, are more ready to enter governments with the right or far right than anything left-of-center.

Since I wrote about youth voters recently, I thought I’d mention that the data basically bear out what I wrote about the results of the European elections back in June: young people vote for the AfD at pretty much exactly the rates as other age cohorts. It’s 39 percent among 18-24 versus 36 percent among those 25-34, 36 percent among those 35-44, and 37 percent among those 45-59 years old. The outliers are, as has been the case in previous elections, the elderly: The AfD had its softest numbers among those 60-69 years old (32 percent) and 70 and older (19 percent!). The young are no firewall against the AfD; but by the same token it’s important to note that until you look at the post-70 set, age just isn’t much of a factor for voting AfD. For Americans who are used to the young voting left because they are more diverse, it is important to note that that probably isn’t true for Thuringia. Although immigration appears to be top of mind for voters here, there aren’t actually that many immigrants in the state.

In case there’s any hope attached to the numbers for the BSW — a populist party which can sound pretty xenophobic and authoritarian, but still considers itself leftist (thank God for small favors, right?) —, the age breakdown puts a damper on that too. The BSW is cleaning up among older generations: 19 percent among those 60+, versus 12 percent among those 18-24. These are longstanding Die Linke-voters abandoning their former party, not new voters coming into a more broadly position leftist fold.

Finally, notice who is barely on the board at all, which is the liberal FDP. A partner in the governing coalition at the federal level in Berlin, their numbers (1.2 percent in Thuringia, those are Animal Rights Party numbers!) should put them in the “also ran” category. It’s interesting that the FDP has basically joined the CDU in rushing to the right on immigration and culture war stuff, hoping to siphon off some AfD-adjacent votes. And it’s further interesting that this has worked a tiny bit for the CDU, but seems to have led to an absolute flameout for the FDP.

There’s some evidence to suggest that people are flocking to the CDU in order to block the AfD from taking power — so the choice of CDU over the FDP may be strategic. However, it’s worth noting (as I did in The New Republic back in 2020) that both the CDU and the FDP were prepared, in 2020, to have one of their own — the FDP’s Thomas Kemmerich — elected governor with the support of the AfD. So it’s not quite clear how firm of a bulwark these parties really would be. (Kemmerich lasted only days, as Angela Merkel basically told her party that any cooperation with the AfD at the state level was a no-go. Ramelow got his old job back.)

The next few days will show whether the CDU will attempt to (a) govern “around” the AfD, as it were, an option that probably would involve a coalition with BSW (oddly enough, the CDU has had a longstanding policy of no cooperation with Die Linke, but for reasons having absolutely nothing to do with rank opportunism did not extend this policy to the tankies of BSW). Or (b) whether it will seek to govern with the far right. It seems unlikely to me that they will choose option (b) … yet. As I wrote in n+1 earlier this year, it’s hard not to sense the frustration on the CDU’s right flank at having a perfectly viable coalition partner available to them and to be barred from making common cause with them on the mere technicality that … they are Nazis. But option (b) is quite probably coming, and every election that turns out like this will make it more likely.

People living in Germany, especially those whose last name, skin tone or religion suggests something less than a Nazi grandpa, will tell you that it almost doesn’t matter whether the AfD ends up in governing. After all, the media and political classes will continue to proceed as though the AfD were in charge already. The AfD’s topics and priorities will dominate German politics, even if (and especially when) the AfD is not in charge. Those who do not share the AfD’s priorities will have ever fewer parts of the political spectrum chasing their votes, making policy targeted at them, or even pitching them on those policies. After all, they have to vote for these parties just for the most formal reason of all — the preservation of liberal democracy. You’d like a bike path, a train that arrives when it says it will, cleaner energy, workplace protections, more robust unemployment benefits, you would like to not be discriminated against? Well, you are welcome to fuck right off, because your electeds will be busy figuring out new and inventive ways to make a couple of hundred thousand Syrians miserable.

So it almost doesn’t matter. Almost. Because the Federal Republic of Germany is called “Federal” for a reason: there is immense power delegated to the states (a legacy of a postwar system that was meant to reduce central executive power, but also a legacy of Germany’s hodgepodge unification process in the 19th century). As I wrote in my n+1 piece, entering the government would give the AfD control over “many cultural institutions that depend almost entirely on government funding, an education sector overseen by the state department of education, thousands of civil society projects, foundations, and more.” It would even give the AfD some control over the very watchdogs that are supposed to watch over extremists like the AfD. Much of the German public sphere seems to be pre-accommodating such a takeover — they are almost trial running what it would be like if you had to interview a minister who happened to be a fascist, if it was your job to ask for funding from his office.

But what that suggests is that certain sectors of German society would fall into line with uncanny celerity. Not by agreeing with the AfD, of course. But by accepting its framings, by following where it directs our attention. Having lived through the Donald Trump presidency in the US has given many of us a pretty keen sense of this kind of collaboration: one that never abandons the stance of critical distance, but refuses to ignore, dispel or disengage, to say “this is not a thing and we refuse to cover it as though it were one”. I see a similar shift happening in large swaths of German civil society. In this way too these elections in two pretty-atypical states may become harbingers of what is to come. Very little of it is good.