Notes on Bad-Faith Credentialing

Probably Part 1

[This is a somewhat unusual post, as I am hoping to workshop a few ideas with my followers — as a result, the comments are open to any and all of you. My ideas about this phenomenon are still evolving and taking shape, so please don’t take any of what I say here as definitive. I would be particularly interested in good examples people can come up with. I wrestled with how and what to pick — and I realized the pull of recency bias is enormous, so many of my examples were from like the last 12 months, even though I’ve been thinking about this for like 4 years! I really hope people agree that this is an actual phenomenon and this is actually interesting — but feel free to tell me otherwise in the comments! I’m sure to write more about this, so stay tuned for another post down the line!]

A few months ago, I made a startling discovery. In thinking about campus controversies, cancel culture discourse, and the anti-wokeness panic, I had often found it useful to turn to a term that I thought my colleague, the philosopher and law professor Wendy Salkin, had coined. Wendy writes on “informal political representation” (people who speak for groups just because enough people agree they represent them in some significant way). And she once (I think) used the term “bad-faith credentialing” in talking to me about a phenomenon I had observed in contemporary discourse: the forcible “making-representative” of people who might just be randos, but who are now made to represent the climate movement, Black Lives Matter, or (a perennial favorite) feminism. The term does have some us apparently in medical credentialing, but that’s not what it refers to here. As I said, something about this term seems quite useful, and it really describes a lot of the discursive strategies political actors turn to as it does become indeed harder to decide who represents specific movements, groups of people, identities.

But in a major twist, it turns out that Wendy doesn’t use that term, and thought I had come up with it. Whoever came up with this thing, we both like it, and are planning to write an article about it in the future. But for now, I thought I’d jot down a few notes about what I take to be “bad faith credentialing”, and why I think it’s worth thinking about – all of this is still quite provisional. These are literally the notes I am planning to rely on when sitting down with Wendy Salkin and we actually figure out how to wrangle these ideas into a 10,000 word article.

My thinking and framing here are very much inspired by Wendy’s work, in particular her book Speaking for Others: The Ethics of Informal Political Representation, which is due to appear with Harvard UP in September. Speaking for Others thinks through the vexed, but important, phenomenon of Informal Political Representation, i.e. having someone speak for a group who has not won an election or had any kind of official conferral (and who, crucially, also cannot really lose it). This is a phenomenon that is mostly associated with "particularly … oppressed and unjustly marginalized groups" (2). Wendy points out that this is also why marginalized groups (she’s particularly thinking of Black leaders from Booker T. Washington via W.E.B. DuBois to Martin Luther King, Jr.) have done the most robust thinking about informal political representation, its mechanisms, its promise, its potential pitfalls, and its ethics. They simply couldn’t rely on formal political representatives (city councilors, state senators, members of congress, etc.) to truly represent them. But they were also keenly aware of the dangers that could come with a group/community having no actual power or influence over the people representing them.

She also points out that there was disagreement whether informal political representation was therefore always a sign of deficiency (ideally, we’d have formal political representation, but in the meantime this will have to do), or whether there is a value to informal political representation even when a group is also formally politically represented. Wendy takes the latter view: there is value in informal political representation, not just as a stop-gap or mitigating solution. She lists: “publicly voicing groups’ otherwise neglected interests; making overlooked groups visible to broader publics; making groups visible to themselves as groups by stirring group consciousness in the members of oppressed or marginalized pluralities; serving as communicative conduits between represented groups and their unresponsive lawmakers; and, through each of these, educating public audiences about the represented group.” (6)

Just to make clear whom Wendy Salkin is thinking about, here’s a pretty helpful list from early in the book:

“Me Too movement leader Tarana Burke informally represents survivors of sexual assault, abuse, and harassment. Black Lives Matter informally represents Black communities throughout the United States and beyond. Former Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School student Aalayah Eastmond informally represents not only fellow former classmates but American high schoolers generally, as when she testified before Congress, ‘We are the generation that will end gun violence.’” (2)

I should say that beyond a few exchanges about the specific problems involved in public political or cultural representation, all of what follows is my attempts to use Wendy’s concepts to think through this phenomenon — Wendy is currently on a super well-deserved leave, so I am just kind of off on my own. And I’m sure my description of “bad-faith credentialing” will be neither as careful nor as philosophically informed as whatever she will come up with in the future. But still, I want to have notes ready in case we eventually get to this project.

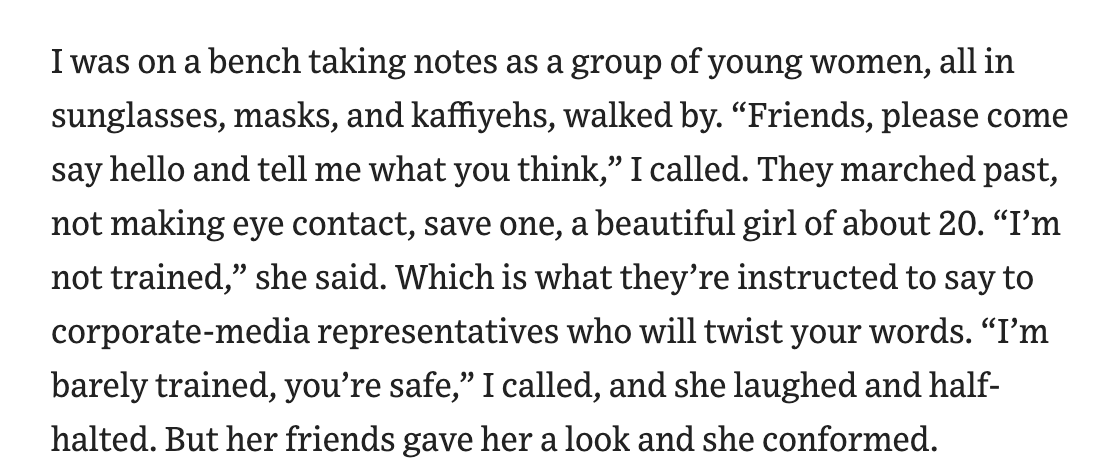

Wendy’s most synoptic definition of informal political representatives is individuals or groups who are “treated by an audience as speaking or acting for others on matters apt for broad public discussion despite having been neither elected nor selected to do so by means of a systematized election or selection procedure.” (3) Notice that “treated by an audience” is a little ambivalent, because the audience presumably includes both people in the group represented and people outside of it. During the protest camps that sprang up at US colleges and universities this past spring, the practice of using spokespeople drew much media attention. Writers – for instance Michael Powell in The Atlantic and Peggy Noonan in the Wall Street Journal – seemed to find this practice deeply problematic and somehow delegitimizing. But what the students were doing was natural: they (s)elected by whatever means someone to speak for them to make sure their points were accurately represented. But I’m not sure that Wendy would think the informal political representations attempted by the students was actually successful: because their outside audience (the reporters) consistently refused to engage with what the IPRs were actually saying. Here is Peggy Noonan’s column about trying to engage with the protestors:

Here is Powell in The Atlantic:

As my friend Michael Hobbes pointed out in an episode of If Books Could Kill on the Columbia protests, Layla Saliba doesn’t actually get to say anything in this piece. We’re told she spoke “at length and with nuance” – did any of those points make it in? Nope. So I think that Wendy would say this isn’t actual IPR: IPR would require that the outside accept Layla Saliba’s role on terms at least somewhat similar to those decided upon inside the encampment. So this is where the question of good faith comes in: two audiences have to ratify each other’s selection. Otherwise you end up with two possible situations: a person whom outsiders recognize but people in the group supposedly represented think is non-representative (*cough* Caitlyn Jenner *cough*), or with Layla Saliba, a person credentialed by the group she represents, but cast aside as non-representative by the outside. A second, related point: If you think about what Powell and Noonan are doing, what they were hoping to have happen (this is another point I’m cribbing from Michael and Peter’s excellent episode) – namely for some random encampment dweller to say something deranged or ill-informed or stupid that they could then slap into the first paragraph of their article – you already get a sense of what I think of as bad-faith credentialing.

Another point of Wendy’s about IPRs that helps clarify something about bad-faith credentialing. Importantly, it seems that the representative is somewhat independent of the group they represent: Fred may represent the residents who think cars are driving too fast on the local road at the council meeting, but he will not represent you on every point. Fred is still Fred, he may differ from some or most of his informal constituents in many, maybe even most other ways. He is not us, he speaks for us on this point. Layla Saliba may be a Andrea Doria Truther (to be clear: I have no reason to believe she is a Andrea Doria Truther), but that doesn’t matter. Because those she represents ask her to represent their views on Palestine and Gaza, not on the fate of the Andrea Doria. The representative is not a figurehead or a quintessence – this seems important, because I think—though this something I’m gonna get into in a second post—in bad faith credentialing the work of representation gets subtly distorted, to the extent that every aspect of the representative comes in for scrutiny (call this the “milkshake duck” of informal political representation).

The reason I’m dwelling on Wendy’s discussion of IPR is that bad-faith credentialing is to some extent a simulation of the process of informal political representation. For that reason it probably also does happen more readily to marginalized groups that don’t have direct and obvious political representatives. In the book, Wendy tells me, “

“I do discuss cases where people are made representatives by an audience although the represented group’s members would not think of them as ‘properly’ representative. So bad-faith credentialing is contemplated within my account of informal political representation (as in, an audience can put someone in the position of IPR whether or not the group would find that person representative in some further sense). This is in fact a central claim in my book, and one that motivates the rest of the account.”

The process Wendy Salkin is interested in—in which an informal representative indeed does speak for, negotiate on behalf of a particular community—can’t really play out if the community doesn’t accept the representative’s representativeness. She’s interested in cases where this works, and she’s interested in it from the perspective of the group (possibly) represented. The majority picking out representatives, or having them represent things their constituents have never selected them to represent them on, seems sort of the most obvious way in which informal political representation can (and often does) go wrong. Can’t wait to see what Wendy says about it in the book!

Again, I think if we return to Peggy Noonan on her bench at Columbia, we can get a good initial sense of what (I think) bad-faith credentialing involves. Peggy Noonan wants to speak to a random protestor and make them representative. There’s nothing wrong with that, except of course the protestors have designated representatives to, well, represent them, a process that Noonan hopes to bypass. Why? Because, presumably, they will say something different from the designated representative. Something that represents the activists differently, more to Peggy Noonan’s liking. You and I might suspect that the bad faith involved is that Noonan wanted to damage the protestors, but I don’t think that’s a necessary condition here. I think what is necessary is that Noonan and Powell thought the spokesperson offered up by the protestors misrepresented what the protestors were “really” like. There is an advance sense of what the represented group must be like and a dissatisfaction with a representative that does not authentically satisfy that sense. That sense can be way off—if you go to a march against a highway expansion project, say, and interview the one guy with a garish poster about circumcision, for instance. Or it can be pretty well-informed—when you’re pretty sure a march is centering a few select fig leaves for what the actual concerns of its participants are. But in bad-faith credentialing there is is a worry that the representatives don’t actually or effectively represent. And it is in bad faith.

So a first definition of bad faith credentialing, modeled on Wendy’s definition of IPR would look like this: Bad faith credentialing is a mechanism that simulates informal political representation, but which chooses its representatives against the wishes of those supposedly represented, and chooses them to the detriment of those represented.”

I’ve sort of made it sound so far as though the bad faith credentialing happens from the outside – i.e. the representative is chosen by those not represented by them. And such cases certainly exist; especially when a previously unrecognized group shows up in a media narrative, media can credential someone just by asking them questions or pointing a camera at them, without the group represented having any veto in the matter.

But I don’t think that’s always the case. Very frequently—think of Peggy Noonan’s appellation of her “friends”, her chumminess and joviality as she lurks on that bench —the bad faith credentialer presents themselves as part of those represented. I say presents, because that insider status is actually quite contingent, always ready to be abandoned over the course of the argument. Imagine the following two-step: as a woman someone points to person X as representing something about feminism; stepping outside of the category, they then criticize feminism for something X believes. This person is neither safely outside of the represented group, nor do they start and end within it.

In moments like this, bad faith credentialing can involve a lot of what is often termed “concern trolling”, but it is not identical with it. “Concern trolling” refers to a simulated concern for a cause or person that actually functions as a criticism (or promotes criticism) of the same. The difference between the two highlights how bad-faith credentialing can pick an ambiguous speaking position: its dishonesty consists in a slippage between inside and outside. You pick out people to address in a particular group/coalition/neighborhood. You pretend at a position within that group or movement and offer what you gesture at immanent critique—you speak to the people you have picked out as being appropriate addressees (“I don’t know who needs to hear this, but…”). “We” shouldn’t sound like this, “we” are less effective, if these are the kinds of things we say or we carry these sorts of signs, engage in these sorts of behavior. The rhetorical stance is: You want the criticized party and the movement you are both implicitly part of to thrive, to be as effective as possible. But what you are in fact doing is stand outside of this same group and are trying to discredit and delegitimate that movement.

This difference between bad faith credentialing and concern trolling highlights some of the history of this language game: it emerges almost organically from leftist practices of immanent critique and a plurality of voices. The reason the inside/outside line can be so effectively mobilized for bad faith attacks is that it is genuinely hard to draw. There is, however, also of course an element of context collapse: the same criticism when uttered at an activist meeting about which posters to make for tomorrow’s protest, will resonate very differently, and will indeed be pretty much a different statement, than when concerns about those same posters show up in a hand-wringing Atlantic article.

And I think this is where bad-faith credentialing isn’t just an inevitable consequence of a complex public sphere. It’s in fact an indicator of a complexifying one, it is an output of the complexification. Firstly, I mean that in terms of media history: I suspect that it’s indeed more common today than it once was, as more people are speaking and being preserved speaking, and there are therefore just more voices to pick out. But secondly, I mean that in terms of political history: bad-faith credentialing emerges more powerfully from a political moment where the left seems gesturally dominant, especially in media, while the people gesturing in left-ish are in fact no longer anything of the kind. A phenomenon I’ve become interested in during the research on my cancel culture book(s) is: people who appear to be on the left, people who certainly rhetorically position themselves on the left, but appear in print or in public only whenever they’re criticizing the left. Some of these people, frankly, sound completely right wing, but … I guess they recycle or something? Acknowledge climate change is real? Who knows! It’s an immensely frustrating discursive position, but one that has clearly become very appealing to much of our pundit class. And my suspicion is that as this kind of position became dominant in media, discursive techniques like bad-faith credentialing almost inevitably follow.

It's a thought-provoking essay and one I'm gonna have to think about for a while, but it also reminds of one thing about that Peggy Noonan piece that really bugged me that no-one else seems to have mentioned: her totally clueless sense of entitlement.

I've canvased on college campuses for a variety of progressive causes and candidates, and one thing I'm certain of: if a 73 year old well-dressed White woman approaches a bunch of college women and starts by saying "Friends, talk to me," their initial instinct is always going to be to turn away. Why on earth does Peggy Noonan think they WANT to talk to her? Someone in her position will more often than not be opposed on every fucking level to what these college kids want.

Turns out that college kids don't want to talk to some old rando who accosts them in order to interrogate them. They've already encountered too many retired folks who've taken on as their personal mission preaching to the college kids about everything (verbatim quote from one such: "Hi. Why do you girls want to murder babies?"). Why does Peggy Noonan think they should trust her? At least the Jehovah's Witnesses just stand there and chat only if they're approached. Maybe if Peggy had worn a big sign around her neck reading 'Trusted Wall Street Journal Reporter' it would have made a difference. Probably not.

Hi Adrian, big fan of the Substack and the podcast. If you've not already read it, I think you'd find this concept of bad faith credentialism really resonates with Olúfémi Táíwò's analysis of epistemic deference here ( https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/being-in-the-room-privilege-elite-capture-and-epistemic-deference ) and in his book Elite Capture. He's also interested in a failure of informal political representation, but not one that always comes from bad faith. Rather, he's interested in how the very experiences and backgrounds that might lead a member of a marginalised group to find themselves as an informal representative in an elite space, could also indicate that they are likely to have had relatively atypical experiences for a member of that group (and so be less representative of the group as a whole). While "epistemic deference" to such representatives ("let's hear from one of the women in the room...") may come from a genuinely laudable place, he argues that it often fails to recognise the filters that prevented so many other marginalised people from getting into the rooms where such conversations happen in the first place. Obviously this can be abused in bad faith ways (eg to manufacture legitimacy for rightwing economic policies that will disadvantage most members of marginalised social groups, but not the most privileged among them), but even if good faith is assumed it seems like a fairly organic outgrowth of the desire among the socially conscious but relatively privileged to find informal representatives of marginalised communities in deeply stratified societies.