He-Men

On the Sword & Sorcery Craze and the Cultural History of Gender -- Part 1

Last night I dreamt I was watching Hundra again. To explain: It’s summer and at times I need to turn off my brain a bit. So I find myself doing a little less serious reading and a little more rolling of 20-sided dice. But it’s hard to turn off your cultural analysis brain, even when your halfling rogue is desperately trying to score a critical hit on that pesky dracolich. Last summer I went on You’re Wrong About to talk about the panic surrounding Dungeons & Dragons in the early 80s. This summer I found myself delving into a different cultural field, a mini-genre that is itself quite self-consciously D&D-adjacent: the Sword & Sorcery film.

In 1980, Columbia Pictures wanted to create a fantasy film drawing on the then-massive success of Dungeons & Dragons. That movie eventually became Krull, Peter Yates’s big budget spectacle about a fortress from space and the handsome prince who has to assemble a D&D style adventuring party to repel the invaders. By the time Krull was released in July of 1983, it was at best in the middle of the pack of a whole host of shockingly similar films — Hundra among them. The Sword & Sorcery films came as quickly as they then vanished from the cultural landscape.

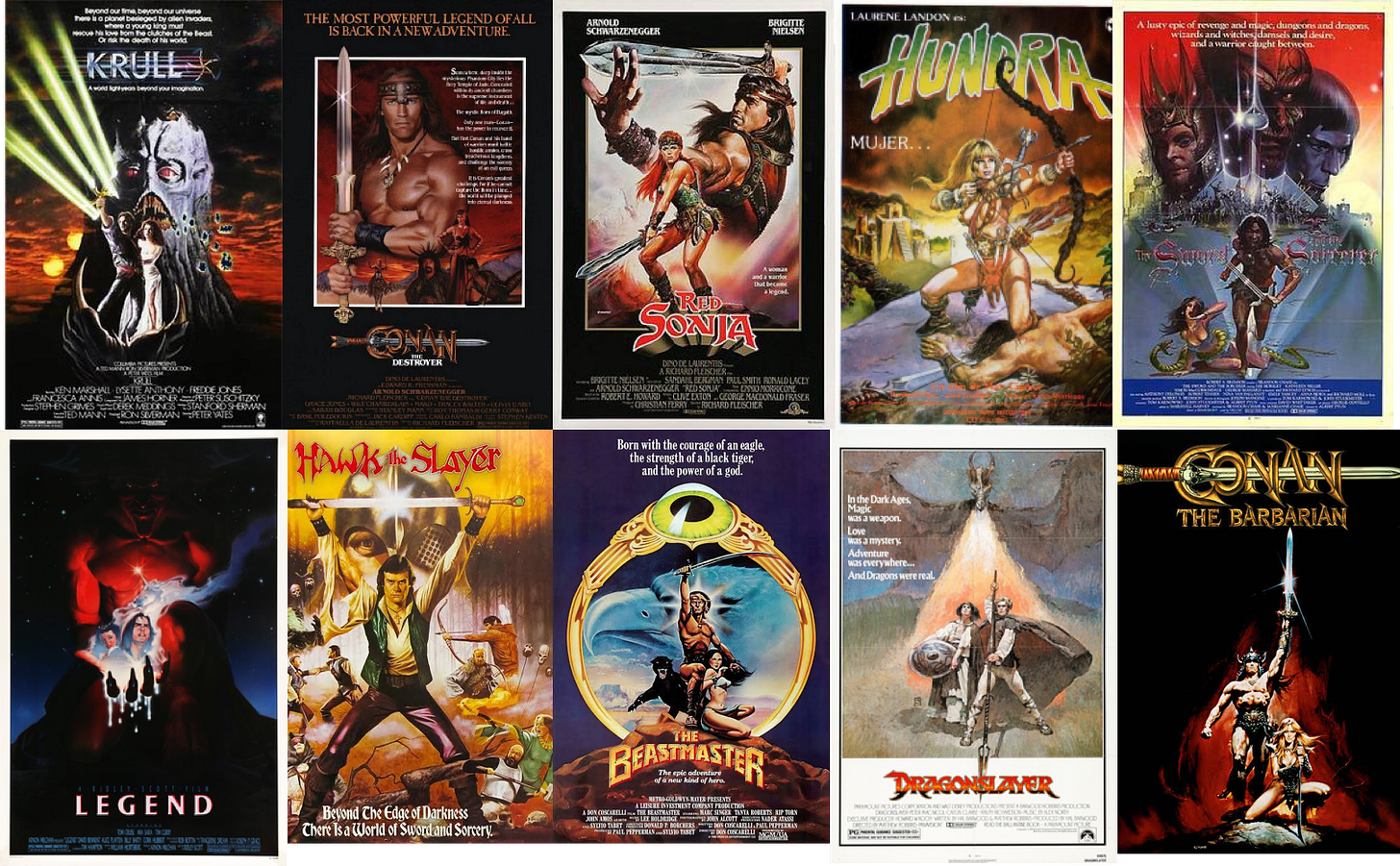

The one most people still remember from that time is of course 1982’s Conan the Barbarian, which made a bodybuilder and sometime actor named Arnold Schwarzenegger into a superstar. But Conan was preceded by several attempts to capture the zeitgeist, the apparently deeply weird, oiled-up zeitgeist, of the early 80s. And it was followed by many more. Hawk the Slayer (1980), The Sword and the Sorcerer (1981), Dragonslayer (1981), two Conan movies and the unofficial sequel Red Sonja (1985), and many, many more or less inspiring knock-offs crowded into (some) cinemas and otherwise onto video store shelves between 1980 and 1985.

I think this is an interesting time capsule for two reasons: it’s a moment when something that had been nerdy and marginal reached for the mainstream. Suddenly things that outcast teens were reading after lights-out was being turned into big budget entertainment. This was a process that didn’t last — the genre eventually became defanged into either children's entertainment, self-parody, or both —, but it’s of course a process that would repeat, and this time complete itself, in the 2010s. After all, today comic books have gone from something that had been nerdy and marginal fare that marked you as a social outcast, to being pretty much 60% of what is playing at the local multiplex, and like 60% of whatever on my streaming services isn’t yet House Hunters International. The 2010s were a time when erstwhile pop culture margins became the center.

That was the true beginning of the moment when every TV show had to tell ongoing stories, when no drama seemed capable of just putting together a good, coherent episode of TV, but forced us to commit to like eight storylines that wouldn’t resolve for another two years, all on the assurance of our friends that “it gets good” after the eighth hour or so. In other words, shows began interpellating their viewers as the opposite of casual consumers — as nerds. Nerds became the norm, normies became the aberration.

There’s a clip from a late night show from 2013, where George R.R. Martin watches clips of people reacting to the Red Wedding – a shocking scene in Season 3 of the show and in A Storm of Swords, Martin’s source novel from the year 2000. In the interview, Martin points out that each of those clips were of course taken by people who knew what was coming and had been shocked by the scene 13 years ago. And now got to use that knowledge to punk the normies. That, I think, was the moment when it became clear that nerd culture had attained some sort of dominance. The culture identified with the person expectantly holding the cell phone waiting for the uninitiated who didn’t know what was coming to react to a joke they weren’t in on. Those who were not absolute nerds about Game of Thrones had become the objects of the cultural gaze, curios and a little goofy much in the way nerds once were.

I won’t hide the fact that I don’t think that this is an altogether good thing, especially because nerd cultural productions, having been made by people who felt themselves to be marginal, even marginalized, can be suffused with a resentment that becomes vicious when fused with any form of dominance. Not for nothing has John Ganz pointed to the central dichotomy of our present fascism as that between jock and nerd. But that’s not my topic here. I want to talk about an early stage of this process, when, in the wake of Star Wars, the fixations of pimply teen boys became something more serious and ambitious. Because yes, the movies I’m talking about today are deeply silly, but they weren’t exactly marginal. They launched a bunch of careers. Conan was conceived as John Milius’s Nietzschean paean to the ubermensch. It was his follow-up to writing Apocalypse Now, for crying out loud!

And that gets us to the more important part of them: they are all about how bodies were interpreted and gendered. Much the same way that Game of Thrones and the Marvel Cinematic Universe probably have a more pervasive influence on the body politics of the 2020s than we tend to realize, these movies articulated and often furthered some really important shifts in what was masculinity. That’s because their ancestors aren’t just Star Wars or Excalibur. Their ancestors are also spaghetti westerns and exploitation films; comic books and Hammer horror. Once Robert E. Howard’s creations (or Gary Gygax’s, in a way) began populating the big screen, in other words, they updated a filmic vocabulary that the Boomers had grown up with for a Gen X audience. A lot of that involved gender.

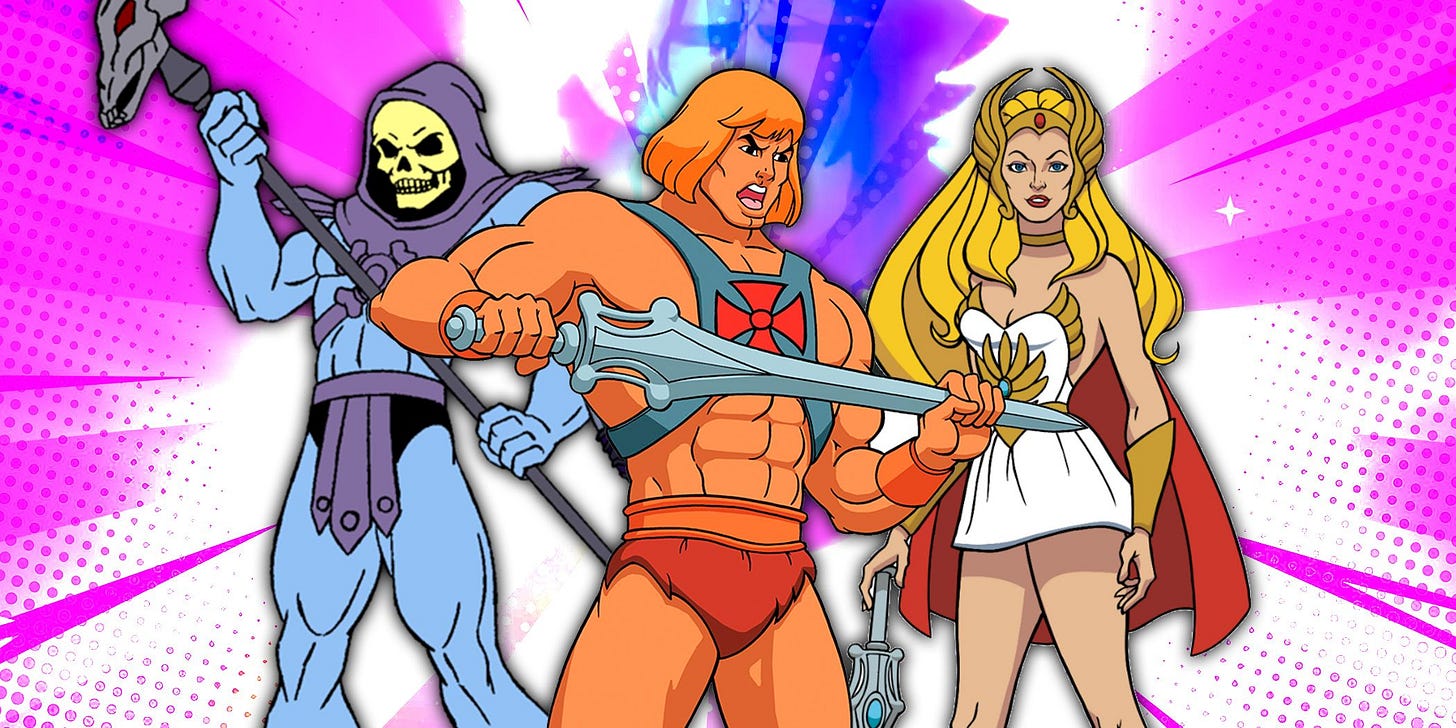

Speaking of Gen X: which part of this phenomenon you’re familiar with might depend on where in that generation you fall. Because while the true exponents of the genre — the Conan-clones filmed in Spanish national parks with an Ennio Morricone score — were cultural artefacts targeting people who were older teens during the first Reagan administration, this was a nerd invasion that — unlike the Marvel invasion of the 2010s — was highly differentiated by age cohort. My parents would not have let me watch Conan in a million years, but all my friends when I was 5 had Masters of the Universe action figures, which greatly resembled the beefcake aesthetic of those films. So I got something similar to kids who were teens when I was in kindergarten, but I also got it in a very different guise. By the time I bought my first D&D book – I must have been 9 or 10 at the time –, I purchased it from the super cool guy working at the local game shop, probably 20 at the time, with impressive white guy dreads, and the nickname “Conan”.

All of which is to say: when we’re talking about Sword & Sorcery epics, there are some overlaps with other genres, and I think those distinctions often coincide with target audiences. And those target audiences are tied up with age. These are fundamentally juvenile pictures, but we’re at a time in the history of youth culture where gradations between entertainments for various age cohorts became not just firmly established, but in fact pretty seriously politicized. This was the sunset of the Age of Aquarius, and the dawning of the age of the Parental Advisory sticker.

Remember that the PG-13 rating was introduced in 1984 (the first film to receive it was, in fact, Milius’s follow up to Conan the Barbarian, the commie-hunting militia flick Red Dawn); and the films that led people to demand this rating – above all Steven Spielberg’s 1984 splatterfest Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom) – coincide with this wave of films as well. There was a lot of concern – maybe a newfound concern – as to what was appropriate, specifically what was appropriate for certain ages, one that started well before the PG-13 rating and that would endure for much of the rest of the 20th century. The Sword & Sorcery wave both participated in those anxieties and represented the more freewheeling time before them, where a few severed heads, some boobs and a fairy tale story aimed at children could sort of inhabit the same movie without one of the studio suits going “huh”.

So besides films like Conan the Destroyer (1984) or Red Sonja (1985), there are high fantasy films à la The Princess Bride or Willow. There were creature centric children’s films like The Dark Crystal (1982), Labyrinth (1986), and of course The Neverending Story (aaaaaah aaah aaah). There were fantasy films that drew more on what’s called planetary romance fiction (think Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars series) – so science fantasy films like Flash Gordon (1980), Masters of the Universe (1987), or Krull (1983). And there were movies that mixed in time travel scenarios – again, Masters of the Universe and The Lords of Magick (1989). Another distinction should probably be made between sword and sorcery and the attempts to class up the genre by either reflecting on the nature of myth itself (The Princess Bride), or to recreate mythology through film. Ladyhawke and Legend are attempts at using mythology to ask basic questions about humanity. A film like John Boorman’s Excalibur (1980), which drew on the Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur with a score drawn from Richard Wagner. Many scenes can resemble ones in their more roided-up peers, but no one would mistake it for Red Sonja.

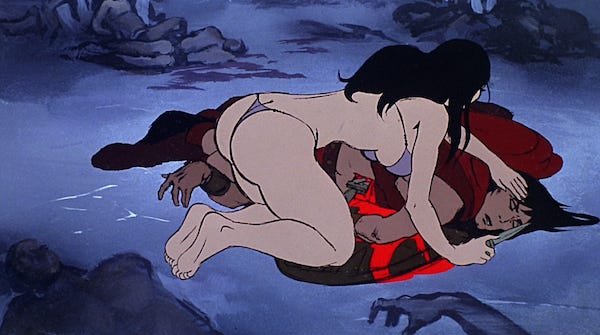

I think this distinction matters because fantasy fare in the early 1980s was strongly bifurcated: you got movies where muscly heroes severed heads trying to free bare-breasted women from giant snakes made of papier maché, and you had movies like Krull that worked hard for their PG rating. This distinction probably also overlapped with different distribution streams: The VHS conquered North America in the late 70s and early 80s, but the direct-to-video market was dominated by exploitation cheapies that catered to more lurid topics. Films like Krull, by contrast, were enormously expensive to make and chased Star Wars and ET money, not Iron Eagle IV money. Sometimes these films diverged in both directions at once: Dan Coscarelli’s The Beastmaster (1982) split the difference, by spawning both direct-to-video sequels (which, albeit entirely tame, really look like pornos on their covers), and eventually an Australian Xena knock-off, essentially a live-action cartoon. So these movies still straddled distinctions that were becoming firmer around that time: Ralf Bakshi’s Fire and Ice (1983) is an animated film that can look like a children’s cartoon, until you get to the themes, and the sheer number of women’s backsides in revealing thongs…

There’s just no easy way to say this: the genre’s immense horniness cuts across the different target demographics and subgenres. It really didn’t seem to matter what demographic a particular piece of media targeted, it was just horny as hell. Whether it’s Bakshi’s booty-crazed children’s cartoon, Arnold’s lubed-up torso, Tim Curry’s distractingly sexy Lord of Darkness in Legend, or — infamously — David Bowie’s omnipresent crotch in Labyrinth, these movies feel confused about the place of sex and sexuality in both their world and ours. They are inappropriate, in part because notions of appropriateness around these kinds of media were still in the process of firming up.

Some of that is about skin. People in these films simply show a lot of it. No one ever seems to wear pants, or a shirt, or a bra. But it’s also about the sweat. Maybe it’s the Spanish locations, but everyone is just constantly perspiring. Unlike the upper-lip sweat of an Eastwood Western, most bodies appear to be perpetually glistening in these films. And where in method acting, as Shonni Enelow has pointed out, sweating on stage was part of showing an actor was working hard, the various semi-professionals that populated the Conan movies (at least in front of the camera) may have sweated because they were in over their heads.

There’s a sense that no one — not the professionals behind the camera, the often novice actors in front of it, not the screenwriters trying out something new and not the studio heads trying to capitalize on a craze they don’t fully understand — knew enough to dose things exactly correctly on these movies. In them, kink aesthetics and adorable critters could still coexist. There was free-floating desire in them, and no one could quite nail down of what type it was and whom it was aimed at. As a gay kid who grew up with a bunch of friends who loved Masters of the Universe, I’m perhaps hyper-sensitive to this — but I distinctly remember a kind of confusion at the time, as to what the fuck adults wanted me to do with these action figures and what among that range of stuff could possibly be considered appropriate. So many pecs, thighs, bulges everywhere — it was a beefcake aesthetic for the kindergarten set. Which is, frankly, absolutely fucking bizarre!

I also can’t help but think that these epically crossed wires are connected to the rise of the home video market. The first VCRs that private citizens could buy and afford came out in 1975. The first video store in the US opened its doors in late 1977 on Wilshire Blvd in Los Angeles. By the time the first Blockbuster opened on October 19, 1985, the US had 15,000 video rental stores. That period coincides with the Sword & Sorcery wave. I suspect that these movies thrived in an environment where the visual cues that told you what kind of a movie you were about to see — prestige or schlock, softcore porno or horror film — were still evolving. One thing I kept thinking as I put together the first graphic for this piece — the one with all the movie posters — was: gee, I’d have a real hard time telling what the hell kind of movie this is from this poster. Is this supposed to be a children’s movie or one for adults? Is this supposed to be titillating or not? This sense of supposed I think is what was fundamentally in flux in these movies. Like the druids, no one knew who they were or what they were doing.

Boorman’s entry into the genre, which clearly prepared the ground for a bunch of the other films, draws attention to the fact that, outside of Conan and Excalibur, these were by and large original stories. Or, in the parlance of the Marvel Age: outside of Conan, most of these aren’t drawing on established IP. There was no attempt to do an Elric movie, or Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, John Carter of Mars. Even the rights to The Lord of the Rings, so central in today’s IP flogging economy, kept bouncing around like hot potato. The attempts to bring Thongor to the big screen sputtered out. The one exception is The Beastmaster, is (I guess?) based on the novel by Andre Norton (really Alice Norton) from 1959, though “inspired by” seems closer to the truth. Some of this may have had to do — again — with the difficult question of target audiences: the heyday of this genre were the years 1980 to 1985, which was a time when Dungeons & Dragons was present in media via a Saturday morning cartoon.

In terms of cultural history, the genre seems to be a merger of three different developments: an early mainstreaming of nerd obsessions (especially D&D); a mainstreaming of 70s body culture into Hollywood film (GLOW, Mr. Universe) and the fracturing of the Western genre.

Let me take these three one at a time: I was surprised to look back to see the impact of D&D on Hollywood. I knew that after starting TSR, Gary Gygax had decamped for Hollywood. I think the reason why I was surprised is because his dungeon crawl through the Hollywood Hills (and, rumor has it, the cursed Mountains of Cocaine) famously came to naught. But I think that’s a very 21st century way of thinking about how nerd culture gets assimilated into Hollywood — where fans reign supreme and a filmmaker “messing up the canon” will yield endless YouTube videos and the occasional death threat. I think the modus operandi in Hollywood circa 1980 was an entirely different one: the professionals would take a look at your silly toy line and then make a movie in which Frank Langella would wear a mask rather than be undead, where characters had entirely different names, and also it was set in LA now for some reason?

In a way, Gygax succeeded in his mission and D&D got suffused in Hollywood — just not in a way TSR could monetize. Because Hollywood was happy ripping off certain motifs and grafting them onto what worked, or what they hoped worked. So these movies are what happens when nerd culture and deep lore meet a bunch of seasoned professionals, some of them working at the top of their game, some of them more or less inveterate schlockmeisters, but in any case old hands. And when those professionals feed the cultural phenomenon through the meat grinder they’ve fed everything else through.

Second point: The early 1980s seem to have been the heyday of people moving from wrestling or bodybuilding into (usually B) movies. Whether it’s Lou Ferrigno’s two Hercules movies, the emergence of former bodyguard Dolph Lundgren or the wrestlers making their film debuts, this was a moment of great porousness between new forms of entertainment and mainstream movies. One of the movies I watched for this project that I had never seen before is Matt Cimber’s 1983 movie Hundra, starring former model Laurene Landon. Matt Cimber (born Thomas Vitale Ottaviano) would later co on to co-create the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling (GLOW) – if you’ve seen the Netflix show about it, the Marc Maron character Sam is clearly based on Cimber.

The third point is perhaps most surprising for those who haven't — like your present tour-guide — consumed a bunch of these movies in rapid succession. These movies were filmed in the ruins of an ecosystem that was just in the process of disappearing. There had been over 600 westerns made in Europe between 1964 and 1978. Even by the mid-70s, most italo-westerns were parodies with Bud Spencer and Terrence Hill – but even their careers were starting to decline. Sword & Sorcery came on the scene as that bumper crop came to an end. Think about a movie like Hundra (1983): if I described to you a movie about a taciturn outsider seeking revenge on the people who murdered their tribe, shot in Spain, with little dialogue, and a few American actors supported by a large cast of heavily accented euros, and the whole thing topped off with a too-much-by-half score by Ennio Morricone, you'd ... picture a Western, no? These movies indeed sound like Spaghetti Westerns: lots of overdubs, lots of extras who seem to have had to learn their lines phonetically, including, I suppose, Ahnuld himself.

But if these are kids playing in the sets and backdrops left behind by The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, it's a very different crew, especially in the gender department. I think it's fair to say that the Spaghetti Western was fundamentally backwards looking in its casting. It sort of disregarded Hollywood casting conventions, but mostly because it could not afford sticking to those conventions. It hoovered up wash-ups, has-beens, Silver Age relics. But if Spaghetti Westerns were a hybrid, or bizarro Hollywood in one way, the Sword & Sorcery pictures were an entirely different one. Instead of washed-up actors, they were open to outsider art. The cast of Conan the Destroyer included: former Mr. Universe Arnold Schwarzenegger, singer and model Grace Jones, NBA star Wilt Chamberlain, professional wrestler Pat Roach and the strongmen André the Giant and Sven-Ole Thorsen.

One side effect of this casting style is that these people couldn't act their way out of a paper bag. But the other was to give these films a blunt physicality. Gender, above all masculinity, was changing outside of Hollywood, and Hollywood wasn’t always catching up. These movies were campy and goofy, but above all they seemed to be deeply ecumenical when it came to body types. And since the conventional actors were often cast as the villain, it was often the heroes who didn’t conform to what an actor was supposed to look like.

Even seasoned actors, like Jack Palance in Hawk the Slayer, seem to have been encouraged to act as unhinged as humanly possible. There was simply no sublimation anywhere on set — the accomplished thespians who didn’t want to be there vamped it to eleven because they couldn’t be arsed to sublimate; and the assorted athletes, starlets, models and strongmen didn’t sublimate because they lacked the range. As a result, the masculinity here was on display in a way that you don’t see in other genres at the time — it is anything but button-up. It leered and dominated, it hissed and chewed the scenery. It was both super full of itself and more than a little hysterical. The masculinity of a Clint Eastwood or Lee Van Cleef in the euro-westerns had been the cool remove of someone who felt he was perhaps better than the movie he was in. The amateurs that populated most Sword & Sorcery films gave it their sweaty, oily all, partly because they literally didn't know how to hold back.

But there’s one obvious change between, say, The Return of Clint the Stranger and Conan. Spaghetti Westerns were an absolute sausage fest, whereas Sword & Sorcery films not only feature lots of ladies, but also have those ladies kick absolute ass. There’s a scene in Hundra (1983), where our heroine finishes eating a turkey leg while overpower a guy attacking her. It’s phenomenal.

It’s a scene that I think gets at why I think these movies are so interesting in terms of their gender politics. Their masculinity is so overstated as to feel sort of sexless. And their women are so jacked, so hardcore and so … different from the kinds of women you tend to get in films from the era, that in spite of all the ubiquitous sexual violence against women that they depict, in spite of all the queer-coded villains, in spite of all the princesses needing rescue, this feels more free-wheeling than most films of the era gender-wise. The logic of bodybuilding was just orthogonal enough to the logic of gender of early-80s America to make the friction between the two kind of interesting.

I realize I promised you Hundra, and I’ve so far not given you that much Hundra. In part II of this essay, I’ll spend some time on some of the individual movies in this mini-genre. So expect a part two with some Conan, some Hundra and some Hawk the Slayer! Hope you’ll come along with me, your trusty Dungeon Master!