Cars, Climate and Self-Certainty

On Agnotology, Gender and Car Culture

A few years ago, I had a conversation with a German visitor to Stanford. He was quite friendly, it was a beautiful California day, and he seemed genuinely curious about the place and its denizens. At some point I mentioned in passing that I drove an electric vehicle. He replied, to my mind without a moment’s hesitation: “well, better not get into an accident, unless you enjoy getting burnt alive.” I don’t know why that struck me as rather off-putting — I had of course read up on this before getting (and putting my then-infant child into) an electric car, and I knew this wasn’t really true. I think what was shocking to me was that he seemed to assume I hadn’t thought about this at all, that I was driving around in a live bomb, waiting for some visitor from the land of Audi to set me straight.

Well, I replied, I do it for environmental reasons, and it’s nice not having to go to a gas stations. Again, his reply was so quick that it almost seemed like he didn’t have to think about it. Well, did I know that EVs were actually far worse during production than gas cars, especially Diesels? Why yes, I was aware of that, though I had read up on that too, but car batteries (unlike gasoline you burn) are recyclable, and besides cradle-to-grave emissions would be substantially lower than in an ICE. But of course it all depends on what’s in your energy mix, he replied. Did I know what was in my energy mix? You might be putting electricity from a coal plant into your car! Well, I replied, there’s only a single coal burning plant in all of California. I live in San Francisco, which relies almost exclusively on renewable energy. And besides, the energy that goes into my car comes almost entirely from the solar panels on my roof, which I am fairly confident don’t burn coal.

The reason this conversation has stuck with me has really nothing to do with the individual points, which I’ve seen recycled in replies, both online and off, every time you say anything about EVs. It’s the uncanny speed with which the visitor replied. Ever since this conversation I got interested in the automatism with which he raised each successive point, and the surety with which each “well, actually” assumed that I couldn’t possibly have contemplated it. There is a particular kind of self-confidence around cars and energy, one interestingly disjunct from actually having spent time looking into these issues. The way certain German observers bring up nuclear energy has a similar dynamic: the country exited nuclear energy recently, and rebuilding this sector would take decades longer than any timetables for global emissions would allow. This would have been true, by the way, even if one had kept running the few extant reactors and then decided to build new ones. And yet there’s this near-automatic need to raise nuclear power in public debate about energy.

I had to think of all of this when my friend Christian Stöcker wrote a column in Der Spiegel about a equally tiny, but strikingly similar incident.

“When my wife recently wanted to get winter tires fitted in a garage belonging to a chain that operates throughout Germany, everything seemed very simple: A friendly young garage employee offered various models, with and without rims. When they looked at the actual car car, the workshop foreman came over and the following conversation ensued.

Foreman: "It's an electric car. We don't do that."

My wife: "Why?"

Foreman: "So much can go wrong! If we unload it incorrectly on the lift, the battery could be kinked. Then it will start to burn."

Christian casts this phenomenon as a case of a “car know-it-all”, and in the case of car mechanics in German garages that moniker may well be right. But I think there is a broader phenomenon, a kind of defensive warding-off of knowledge. These people know — or tell themselves they know — just enough so they can tell themselves they no longer need to know anything more. Invocations of combusting EVs, of "the “energy mix”, etc., are, to misappropriate a phrase from Lionel Trilling, “irritable gestures seeking to resemble knowledge”. A kind of savviness that serves to ward off rather than incite future action. It’s a fancy way of saying “fuck off”.

In the 1990s, my Stanford colleague Robert Proctor pioneered the description of a field called “agnotology” — which studies forms of ignorance, of not knowing, and of not needing to know. Proctor is particularly interested in ways in which politics shapes our ignorance; my Stanford colleague Londa Schiebinger has written extensively about the gendered dimensions of ignorance. Proctor and Schiebinger largely focused (such as in their volume Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance) on how we come not to know what we don’t know. That’s of course a little different from the car mechanics in Christian Stöcker’s story, who took themselves to be quite knowledgeable while being in fact no such thing. But agnotology is all about “structured apathy” — and I think this is where the kind of “know-it-allism” around cars ends up, too. It creates a permission structure where who can even say and have you considered and anyway, watch me do what I’ve always done, but with the added satisfaction of savvy consumerism and knowingness.

For some reason, I remember a discussion (really a fight) my parents had with my grandparents in the 1980s on the subject of catalytic converters, of all things. My parents had gotten a new car that had one (they became standard in that decade, I believe). My grandparents insisted that the converters were dangerous and that their emissions (?) might hurt us children. I’ll at some point have to do a deep dive on weird discourses and conspiracy theories about catalytic converters, some of which appear to the present day. But in the case of my grandparents — two people who were quite car-dependent, but also quite car-ignorant — the value of the talking point of catalytic converters hurting children was simply that they didn’t need to adjust their behavior or worldview in any way. To look at what they were saying in terms of content — misinformation, say, as we might today — is sort of besides the point. We’d need to look at a statement like “catalytic converters are dangerous” in terms of how they are used and how they are useful to their users. In this case, it was just the shape their epistemic closure took; and it probably wasn’t an accident that it took the shape of the car, an object that structured their everyday life without occasioning very much contemplation at all. They were not necessarily “know-it-alls”, in other words, but the car adumbrated the outer edges of what they felt they needed to know.

There’s a famous 1959 essay by Theodor W. Adorno called “Theorie der Halbbildung” — which is sometimes rendered literally as “half-education”, but more frequently as “pseudo-eduction” or “half-culture”. The “half” of course raises the question: what’s the fullness we’re measuring against? True Bildung (so “education”, but also personal formation), Adorno suggested, is an effort at attaining and transmitting autonomy. The deficient form of educatedness, he thought, is all about the opposite: you substitute one form of heteronomy for another. “The authority of the Bible is replaced by the authority of the stadium, television, and ‘true stories’ which claim to be literal, actual, on this side of the productive imagination.”

What I think he means is simply this: part of Bildung is about taking an imaginative distance from what happens to be the case, or what we’re told just happens to be the case. This is what he means by “productive imagination”. We get to ask: is what I am being taught correct? Is it right? Is it inevitable? Is it even so? But the culture industry, Adorno claims, hems in that sense of possibility, it affirms that what is is the only way it can be. And we are invited to feel educated, feel informed, feel savvy by simply regurgitating what we’re told is simply the state of affairs, “the world we live in”. You can see the regressive, dehumanizing aspect of this invitation in discussions of immigration, for instance, where the most unhinged, bizarre, science-fiction proposals about mass invasion from the global South and mass deportations can be labeled “realism”, while people pointing to, you know, human rights and the realities of how borders actually work are being treated as hopelessly idealistic.

But something similar is, I think, behind the exchanges I opened with. There is an accommodation and over-identification with the status quo. And there is an sense of someone casting about desperately for an objective constraint to orient themselves towards. A reason not to use their imagination, not to question too much, not to have to justify. Modern-day contrarianism of course very frequently has this dual positioning: it understands itself as standing-apart, as thinking-for-itself. But it does so by reference, and at times even submission to, a very circumscribed set of alternative ideas/facts/observations. It is both anti-formulaic and simultaneously deeply formulaic. It doesn’t accept the “official” version of events, but seems strangely wedded to questions whether jet fuel can melt steel beams. In some truly beautiful cases, the contrarian ends up in a bizarre and utterly place all his own. But more often than not, the questions he’s constantly “just” asking are questions he is parroting — from millions of others online, from wealthy interests who have astroturfed them, from conservative politicians who have repeated them endlessly on the stump. It’s a simulation of autonomy that is ultimately about total fealty to a very specific vision of the world, one imposed almost entirely from the outside.

Now, “a very specific vision of the world, one imposed almost entirely from the outside” that simulates autonomy? Doesn’t that sound very much like car culture? So it doesn’t feel totally shocking that the car would become a locus of this kind of slippage. In car culture we are almost constantly invited to take whatever people who are way more powerful than us, and who couldn’t give less of a crap about us, and call it freedom. Yes, to call it a freedom to be guarded and cherished, even though it didn’t even come optional until a few years ago. Where features, traffic rules, perks that we dismissed as pointless and unnecessary a few years ago become privileges that we defend with deep and abiding commitment. Agnotology, for Proctor and Schiebinger, is always also a study of power. Mostly because things we don’t know and are told we don’t need to know or told are unknowable are often enough indexes of power. But also because in not knowing, in not caring to know, we choose our heteronomy. We choose which powers-that-be we align ourselves with.

The car is a prime vehicle (ha!) by which this kind of choice can be made. You can be a driver, of course, and not have any aspects of your personality flow from that fact. But the moment you speak politically as a driver, you tend to make certain claims about the broader world and how it is and should be constituted. And those claims tend towards the structurally conservative. There’s some research into situational materialism, i.e. the selective activation of your attachment to certain consumer goods or comforts, and its impacts (often gendered impacts) on climate skepticism. But really, driving makes us attached to almost everything around us in a particular way: You want to retain neighborhood character and the amount of space dedicated to residential parking. You want to maintain the specific mode of access you require to the nearby city and its amenities. You fixate on the “flow of traffic” as a good in itself, one that pertained to a certain road two, five, ten years ago and that — even if historically it’s always been congested — one could, with sufficient effort get back to.

In other words, the car plugs you directly into the heart of the status quo, it identifies your interests with the status quo. And yet it seems to require language games that allow you to understand that identification as independent, as thoughtful, as individual. This is, I think, where this know-it-all-ism comes from. It’s a form of technophilia as an avoidance strategy (whereby any internal contradictions you experience in the hear and now become solvable through some vague future technology). It’s an appeal to authority that nevertheless understands itself as fundamentally heterodox (usually in opposition against some “environmentalist mainstream” that mysteriously doesn’t appear to be very environmentalist or else not very mainstream). And Christian Stöcker’s text also suggests it’s a form of gendered knowingness. He thinks it isn’t an accident that whatever else those car mechanics did, they also were mansplaining to his wife:

“But there is a completely different problem on the German market, namely the German car man. I deliberately write man, because car know-it-alls in Germany are primarily a male domain. Unfortunately (for VW and other manufacturers), a significant portion of German car know-it-alls now seem to enjoy the role of aggressive EV know-it-alls.”

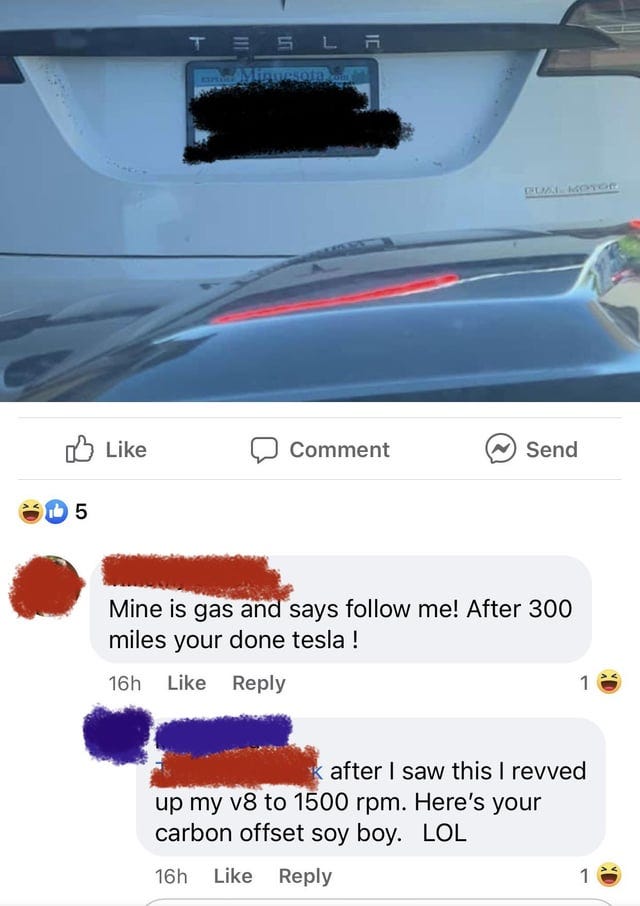

This seems generally right to me. It’s not men, it’s masculinity — being aggressively knowledgeable about EV has become a style of masculinity. Knowingness about cars has long been a privileged arena for expressing it, and fighting off EVs has become a way of defending it. This goes twice over for rearranging cars in ways in which “they” don’t want you to: tuning them, hot rodding them, etc. etc. There is also an interesting link (which Christian explores in his book) between climate nihilism and masculinity — it’s not an accident that conservation, recycling, climate anxiety are so insistently feminized in the conservative (and even liberal imagination), while so many overtly insane forms of climate contrarianism (think “rolling coal”, which I wrote about a few installments ago) are understood as macho. Some version of this will be familiar to you if you’ve spent any time on social media (the image below is an exchange on Facebook I found on Reddit) — or simply in society.

The car, which we are invited to use with so little thought, which plugs us into economies way beyond our understanding, is a perfect place locus for deciding what we don’t need to know. For our own ignorance to become directly fused with our identity, our selfhood, our self-worth. And with our capacity to harm ourselves, others, and our planet. In conceptualizing my book I often go back to the famous line Nick Carraway has at the end of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.” It’s my instinct that this line contains what car culture sells us as an aspiration: you get to smash up things and creatures and then retreat back into… well, not your money, because you’re still paying off this dumb thing, but at least into some kind of vast carelessness. That is the promise of our cars, not as object, but as an attitude towards society made manifest. The promise is ultimately one of carelessness, of not having to know.