[NOTE: Once again I am providing a German version of the text first; the English translation is below, though — so please feel free to read on! I will have another German-English entry next week – on the practice of “Gendering” in German academia and what I was able to find out about its impact on academic freedom –, after that, I think this will become a more anglophone newsletter. I hope that’s alright!]

Nach einem Vortrag Anfang des Monats sprach mich ein Herr auf mein Buch an und warf mir “Verharmlosung” vor. Er hatte mein Buch nicht gelesen, aber er hatte “über mein Buch gelesen” – und je nachdem, welche Rezensionen er gelesen hatte, verstehe ich gut, warum er diesen Eindruck von meinem Buch hatte. Ich möchte ihn keinesfalls falsch wiedergeben, aber ich kann mich an die genaue Formulierung nicht mehr erinnern. Die Verharmlosung, um die es ihm ging, war, soweit ich es verstanden habe, jene: Es existiere eine linke Zensurkultur an amerikanischen Colleges. Ihr seien in den letzten Jahren “hunderte” (konservative oder anderweitig gegen den linken Mainstream aneckende) Professor:innen zum Opfer gefallen. Er nannte die Zahlen aus einem Artikel im Boston Globe – eine von Steven Pinker und Bertha Madras lancierte Erklärung zur Neugründung einer Art Arbeitsgruppe für akademische Freiheit an der Universität Harvard.

Ich möchte dem Herrn auf keinen Fall zu nahe treten, und es ehrt ihn, dass er (wie er mir zwischenzeitlich schrieb) mein verharmlosendes Buch liest. Aber ich fand sowohl die Statistik, die er zitierte, als auch die Art und Weise wie er sie zitierte, äußerst bezeichnend für den Diskurs über “Cancel Culture” in Deutschland. Und deshalb möchte ich mich heute mit den von ihm vorgebrachten Daten genauer beschäftigen. Ich erwähne den Herrn, dem ich den Verweis auf diese Daten verdanke, nicht, um ihn irgendwie zu diffamieren, sondern weil die Daten, auf die er sich bezog, ja in dem Artikel standen, um von Menschen wie ihm so benutzt zu werden. Menschen, die sich Sorgen machen um die Meinungsfreiheit, und die meinen, ein Text von Steven Pinker im Boston Globe sei eine einigermaßen objektive Quelle für den Stand der Meinungsfreiheit in den USA.

Hier die Passage, der mein Gegenüber sein Verständnis der Dimension des Problems entnahm:

Ich verstehe komplett, warum mein Gegenüber diese Zahlen so interpretierte. Aber die Frage ist natürlich, ob die Zahlen so stimmen – und ob sie bedeuten, was dieser Text impliziert, dass sie bedeuten. Der Artikel diagnostiziert eine “Ernüchterung” “der” Amerikaner betreffend ihrer Universitäten – wer auf den Link klickt, wird sehen, dass die Statistik von Gallup Polling, auf die Pinker und Madras verweisen, eigentlich vor allem besagt, dass Republikaner in den USA von den Universitäten abzurücken scheinen. Es wird also von Beginn an eine Entfremdung rechtsgerichteter US-Wähler mit einer Entfremdung der Amerikaner gleichgesetzt. Irgendwie machen die Unis es Rechten nicht recht. “Zu dieser Ernüchterung,” so Pinker und Madras, “trägt nicht zuletzt der Eindruck bei, dass die Universitäten Meinungsverschiedenheiten wie die Inquisitionen und Säuberungen vergangener Jahrhunderte unterdrücken. Es wurde durch virale Videos von Professoren angeheizt, die gemobbt, beschimpft, zum Schweigen gebracht und manchmal angegriffen wurden, und es wird durch einige alarmierende Zahlen bestätigt.” Gemeint ist – sagen wir es klar – linke “Cancel Culture”, die hier mt “Inquisitionen und Säuberungen vergangener Jahrhunderte” verglichen werden – Torquemada mit they/them Pronomina.

Der Artikel spricht von “156 Demissionen zwischen den Jahren 2014 und 2022” – das entspricht etwas mehr als 17 pro Jahr.(1) “Mehr als während der McCarthy-Ära”, vermerkt der Artikel. Die McCarthy-Zeit umfasst die Jahre 1950 bis 55 (oder ‘47 bis ‘56, wenn man eher von einem Kulturphänomen (Red Scare) als von den zentralen Persönlichkeiten ausgeht). In diesem Zeitraum haben nach der Zählung von McCormick und Holmes “ungefähr 100” Professoren an Colleges und Universitäten in den USA ihren Job verloren (im Vergleich zu 500 Lehrern an Schulen, z.B.). Auch diese Zahlen sind schwierig zu erheben, zumal aus der zeitlichen Distanz; wir vergleichen also Schwammiges mit Schwammigem. Dennoch läßt sich sagen: Die absoluten Zahlen, die FIRE anführt, übertreffen die aus der McCarthy-Ära in der Tat – je nachdem, welche Jahre dazugezählt werden, dürften die Demissionen pro Jahr in der McCarthy-Ära allerdings höher ausgefallen sein (um das genau beantworten zu können, müssten wir die Datenbasis einsehen können, die Pinker et al hier zugrunde legen).

Trotzdem: Genauso schlimm wie McCarthy, oder fast so schlimm wie McCarthy ist schlimm genug! Nur sollte man den Nenner mitbedenken: Um 1950 gab es in den USA laut Department of Education gerade mal 1800 Universitäten und Colleges. Heute sind es (je nachdem, welche Institutionen man mitzählt und welche nicht, zwischen 5000 und 6000. Die Zahl der an diesen Campussen Lehrenden sprang allein zwischen 1950 und 1990 von 190.353 auf 987.518 – also eine Verfünffachung. Heute liegt die Zahl der “professors, associate professors, assistant professors, instructors, lecturers, assisting professors, adjunct professors, interim professors” laut Department of Education bei 1,5 Millionen.(2) Daraus ergibt sich ein statistisches Problem: Wenn etwas 100 von 190,000 Menschen passiert, ist eindeutig häufiger als etwas, das 156 von 1,5 Millionen Menschen passiert. Dieses “schlimmer als McCarthy” scheint demnach kalkuliert, die absolute mit der relativen Häufigkeit eines Phänomens miteinander zu verwechseln.

Als eine reine statistische Beschreibung mag das stimmen (mehr dazu später), aber diese Form der Präsentation verzerrt doch auf bedenkliche Weise die Daten. Wenn wir vor einer neuen Zensurwut und Moraldiktaten warnen, zumal in Europa, hat man doch ziemlich genaue Vorstellungen, wer zensiert und warum. Junge, woke Studierende zensieren insbesondere konservative Professor:innen für Äußerungen, die ihnen nicht gefallen. Der Herr, der mich mit dieser Statistik konfrontierte, scheint sie genauso verstanden zu haben: Für ihn verharmloste ich die linke Zensurkultur, die in den USA von linken Woken ausging. Und ich glaube, das lag nicht daran, dass er den Text falsch gelesen hatte – er hatte nur herausgelesen, was Pinker et al in der Tat suggerieren. Aber die FIRE-Liste zählt nicht nur diese Art von Fällen; sie versucht vielmehr, alle Fälle aufzuzeichnen, in denen jemand seinen Job wegen Äußerungen verliert, die möglicherweise durch den ersten Verfassungszusatz der USA geschützt sein könnten. Es ist einigermaßen unredlich, konservative Zensur linker Professoren umzudeuten zu Indizien für eine linke Zensurkultur. Genau deshalb bemüht der Pinker-Text McCarthy: er will suggerieren, dass alle 156 Fälle aus derselben ideologischen Richtung kommen – wie eben während des McCarthyismus. Wenn 1951 ein Professor (illegalerweise) aus Amt und Würden gedrängt wurde, weil er mit der Frau des Dekans durchgebrannt war, dann wäre er kein McCarthy-Opfer.

Nun kommen wir zum letzten Aspekt: den Zahlen selber. Ich habe die betreffende Passage gescreenshotted, man kann daher leider nicht auf den Link klicken. Das ist schade, denn der Link ist einigermaßen frappierend: er führt nämlich nicht etwa auf eine Auswertung von Daten, in denen wir dann die 44 De-Tenurings, 877 “attempts to punish” und so weiter nachlesen können. Er führt vielmehr auf die Liste der FIRE Foundation selber. Wir können uns also als geneigter Leser:innen entweder diese Zahlen selber erarbeiten – oder wir müssen ihnen einfach vertrauen.

Ich sollte sofort sagen, dass ich das Anliegen der Foundation — übermächtige Institutionen zu benennen, die mit ihren Arbeitskräften oft viel zu willkürlich verfahren — absolut wichtig und richtig finde. Ich denke aber, dass die Suchmaske, die FIRE anbietet, dazu da zu sein scheint, genau so gebraucht zu werden, wie Pinker und Kollegen das taten. Und dabei sehe ich ein Problem, das ich heute versuchen werde, zu demonstrieren. Zusammen mit meinem Mitarbeiter Eren Yurek habe ich rekonstruiert, wie Pinker et al diese Daten erhoben haben dürften. Sie haben zwischen den Jahren 2015 und 2022 nach Einträgen gesucht, in denen die Metadata den Sachverhalt “contains termination” erfüllt.

Eren und ich haben deshalb dieselbe Suchmaske genutzt und uns Datensätze für die einzelnen Jahre zusammengestellt. Rein Zahlenmäßig haben Pinker et al Recht: die FIRE-Datenbank listet 156 Fälle zwischen 2015 und 2022, in denen “Termination” in der Metadata vorkommt. Hier die Verteilung durch die Jahre:

Zunächst einmal bekommt man nicht den Eindruck, dass die Zahl kontinuierlich ansteigt (das haben Pinker und Kollegen allerdings auch nicht behauptet). Der Eindruck ist zunächst einmal, dass sich die Zahl der Demissionen irgendwo um die 15 pro Jahr bewegt, und dass es ein Ausreißerjahr gibt. 2020 — das Jahr von COVID, Lockdowns, Black Lives Matter, Präsidentschaftswahl, “Stolen Election”, das Jahr in dem wir alle daheim hockten und uns nur in den sozialen Netzwerken austoben oder per Zoom unterrichten konnten — stellt, vielleicht nicht ganz überraschend, den (vorläufigen) Höhepunkt dieser Statistik dar. Es ging eindeutig hoch her in dem Jahr, und die Warnung vor einem sich eintrübenden Klima für akademische Freiheit lässt sich in diesem Jahr wahrscheinlich am ehesten aufrecht erhalten. Schauen wir uns die Fälle einmal an.

Von den 37 für 2020 gelisteten Fällen betreffen 29 laut FIRE Konsequenzen nach Beschwerden “von Links.” Diese reichen allerdings von absolut diskussionswürdigen Fällen (einmalige Verwendung des “N-Worts”) zu politisch nicht wirklich verortbaren. Dass zum Beispiel Professorin Diane Klein (University of La Verne) gehen musste, weil sie die Ermordung ihres Dekans nahelegte, oder Thomas Brennan (Ferris State University), weil er in wirren Posts die Realität der Mondlandungen und Atomtests in Frage stellte, hat mit “rechten” oder “linken” Positionen eigentlich nichts zu tun – und dass die Unis sie hinauswarfen wohl auch nicht. Insgesamt hatten 13 der involvierten Professoren “Tenure” – waren also eigentlich unkündbar.

Wer sich die individuellen Fälle anschaut, der merkt schnell: Das Problem mit diesen Zahlen ist nicht, dass hier ein grober statistischer Fehler begangen wird, sondern vielmehr, dass an jeder Stellschraube ein bisschen gedreht wird, um die Zahl noch ein wenig nach oben zu kaprizieren. Von den 37 “geschassten” Professor:innen sind zwei weiterhin in Amt und Würden – wir nehmen an, dass die Datenbank einfach nicht auf den neuesten Stand gebracht wurde. Eine weiterere verließ ihren Job für einen neuen, wurde aber laut Arbeitgeber nicht gefeuert. 2 weitere sind gar keine Professor:innen, sondern waren “doctoral students”, die aus einem Doktorandenprogramm geworfen wurden; ein weiterer Fall hat mit einem Postdoc zu tun. Im Fall eines Altertumsforschers in Princeton fand eine erste Beurlaubung 2018 statt, die Demission 2022. FIRE listet seine kontroversen Aussagen 2020 und suggeriert, er sei wegen diesen hinausgeworfen worden. Die Vorwürfe wegen sexueller Belästigung, die die Uni als Grund für die Demission angab, und die Jahre, in denen diese relevant waren kommen nicht vor.

In einem weiteren Fall verhinderten Kolleg:innen die Beförderung einer Professorin auf eine Dekanstelle (die Datenbank wertet das als “firing”), ein paar Jahre danach wechselte sie an eine andere Uni. Zwei weitere wurden ohne Bezahlung beurlaubt, scheinen ihre Job allerdings behalten zu haben. Insgesamt bekamen 8 der 37 ihren Job im Endeffekt zurück, entweder nach öffentlichem Druck oder nach Klagen.

Bei vielen weiteren gab es nie eine Demission, ihr Vertrag wurde nicht erneuert. Was natürlich auch gefährlich sein kann, nur dass hier Kausalität sehr schwer zu klären ist — und sehr leicht zu behaupten. Insgesamt handelt es sich bei 6 der 37 um “Adjunct Professors”, die also gar nicht vollzeitlich an der Universität sind, sondern nur von Kurs zu Kurs angestellt werden (eine absolute Unart des amerikanischen Universität, nebenbei gesagt). Vier weitere sagen, dass ihre Verträge nicht verlängert wurden, weil sie unliebsame Aussagen tätigten. So etwas kommentieren Universitäten aus Prinzip nicht, eine Gegendarstellung gibt es also nicht. Viele dieser Fälle dürften auf Missstände im amerikanischen Universitätswesen verweisen — schamlose Ausnutzung, mangelnde Loyalität vonseiten der Verwaltung, und Abhängigkeiten – aber eben nicht auf ein und denselben Missstand. Hier werden sie nach dem Prinzip “reim Dich oder ich fress Dich” kombiniert.

Zum Beispiel: 4 der 37 waren Musikprofessoren am College of Saint Rose in New York. Das College feuerte 2020 die vier Professor:innen (alle mit Tenure) — die Universität sagt, aus Kostengründen. Die Professor:innen sagten, es habe mit Kritik an der Musikfakultät als “zu weiß” zu tun. Auf der FIRE Webseite sind die vier ganz selbstverständlich Teil der 37 — mit dem Vermerk, ihre Cancellation sei “from the left” gekommen. Und Pinker et al zählen die vier anscheinend unter den 44, die aufgrund ihrer freien Meinungsäußerungen ihre Tenure eingebüßt hätten. Das stimmt allerdings gleich doppelt nicht: die Uni sagt, wie gesagt, man habe Geld sparen müssen (ein Unding, aber ein anderes Unding, als FIRE hier dokumentieren will). Und zweitens klagten die Professor:innen erfolgreich gegen ihre Demission — die Entscheidung der New York Supreme Court erwähnt die angebliche politische Dimensionen des Falls nur ganz am Rande. Das Gericht sah es vielmehr als erwiesen an, dass das “Music Department in violation of its own procedures,” gehandelt habe, “using inadequate, inaccurate, and misleading financial data, while retaining members of the same Department who were lower in rank and years of seniority, including those who had not been awarded tenure.”

Von den 13 Professor:innen mit “Tenure”, die für 2020 in der FIRE-Liste stehen sind also: 4 aus Budgetgründen weggekürzt worden, wogegen sie erfolgreich geklagt haben; eine Person hat mitnichten ihre Professur verloren, wohl aber eine Beförderung nicht erhalten; eine Person hat den Job gewechselt; zwei stehen nur aus Versehen auf der Liste, sie wurden zwar kritisiert, haben ihren Job jedoch behalten. Es bleiben 6 Fälle. 2020 zählte das National Center for Education Statistics 189.692 Professors (per definitionem mit Tenure) und 162.095 Associate Professors, die an den meisten (aber nicht allen) Universitäten ebenfalls Tenure haben. Das bedeutet, es gibt irgendwo um die 325-350.000 Menschen mit Tenure, von denen 6 im Jahr 2020 – dem Jahr von COVID, Lockdowns, Black Lives Matter, Präsidentschaftswahl, “Stolen Election”, Zoom Meetings – ihre Tenure einbüßten.

Mehr noch, wenn wir uns zum Vergleich die Zahlen für das Jahr 2016 anschauen, stellen wir fest, dass die Zahlen ganz ähnlich aussehen. Die FIRE Liste für 2016 listet 15 Professor:Innen, die ihren Job verloren haben. 9 von diesen hatten/haben Tenure. Von diesen wurde einer nicht wirklich gefeuert. Und, nur falls es für Sie von Interesse ist: Naberhaus, Barthold, Fulton und Hawkins sind in der FIRE-Liste als “von rechts” Gecancelte aufgelistet.

Was auffällt, ist die geringe Zahl von Adjuncts/Lecturers — diejenigen Personen, deren Vertrag einfach nicht verlängert wurde im Datensatz von 2016. Ich war 2016 an der Universität, und ich kann mir beim besten Willen nicht vorstellen, dass damals weniger unfair mit “adjuncts” umgegangen wurde. Ich habe den Verdacht, dass damals einfach das “Cancel Culture”-Narrativ noch nicht so richtig existierte — und dass man einfach nicht auf solche Fälle geachtet hat. Die Verschiebung zwischen 2016 und 2020 scheint im FIRE Datensatz auf dieses — häufig ausgeblendete — Segment des akademischen Prekariats zurückzugehen. Man hat angefangen, bei solchen Fällen nachzufragen und zu protestieren — aber eben nur dann, wenn sie in ein politisches Narrativ passen.

Im Endeffekt müssen Sie sich selber überlegen, wie Sie diese Zahlen bewerten. Man könnte sagen, dass ein Fall schon ein Fall zuviel ist. Aber viele dieser Fälle erzählen die Geschichte eines langsamen Zerwürfnisses zwischen Universität und Professor: in manchen würde ich ganz klar die Partei des/der Professor:in ergreifen (Lora Burnett war eine offen linke Stimme auf Twitter, ihr neuer Uni-Präsident ein Trump-Intimus; einige der Professoren scheinen in der Tat nur dumme Facebook-Postings abgesetzt zu haben), in anderen muss ich zugeben, dass ich die Sicht der Universität schon verstehen kann: wie geht man um mit einem Kollegen, der öffentliche Zoom-Meetings mit wirren, anti-semitischen Verschwörungstheorien stört?

Und gerade daher hinkt der Vergleich mit McCarthy so eklatant: denn erstens ist es ja etwas anderes, ob etwas vom Parlament, vom Staat verordnet und forciert wird, oder ob sich etwas zivilgesellschaftlich herausbildet. Eine Mehrheit der Amerikaner haben 2020 kollektiv beschlossen, anders über Rassismus nachzudenken und anders auf ihn zu reagieren (viele, viele konservative Amerikaner übrigens auch). Ob eine Vita dem zum Opfer fällt (oder z.B. der Tatsache, dass Frauen anfangen, offener über sexuelle Belästigung durch Professor:innen zu berichten) ist schon etwas anderes als wenn eine Regierungsinstanz an Professoren ein Exempel statuiert.

Aber noch viel wichtiger: wenn man sich die wichtigen Fälle während McCarthy anschaut, fällt auf, wie ähnlich sie gelagert waren. Es handelte sich eigentlich immer um dieselben Fangmechanismen (Loyalty Oaths, Denunziationenn vonseiten der Politik, Ehemaligen, oder der American Legion), dieselben Gerichtsbarkeitsformen (Universitätskommittee) und eine sehr kleine Anzahl möglicher Resultate (in den meisten Fällen glücklicherweise keine Demission oder Resignation). Bei der FIRE-Statistik ist die Streuung hingegen extrem, selbst wenn wir die Darstellung der jeweils “Gecancelten” zugrunde legen. Was wir uns vorstellen sollen, wenn wir hören “156 Professoren”, dann wohl einen Fall wie die zweier Professoren an der Louisiana State University: unwirsche, rassistische Kommentare auf Facebook über BLM; wütende Reaktionen von Kollegen und Studierenden; Demission. Um es ganz klar zu sagen: diese Fälle finden sich in unserem Datensatz im Jahr 2020. Aber es sind (je nachdem wie wir stark wir den verschiedenen Darstellungen glauben) so ungefähr ein Viertel der 37 Fälle. Der Rest ist da, um die Drohkulisse zu verstärken.

(1) Ich bin gerade die Zahlen noch einmal durchgegangen, und der Text muss meinen “zwischen dem 31.12.2014 und 2022.” Denn wenn man das Jahr 2014 dazurechnet, ergeben sich bei den Demissionen, die auf der FIRE-Webseite nachzulesen sind, 165, nicht 156.

(2) Man sollte dazusagen, dass die Statistik nicht Professor:innen betrifft, sondern Lehrende (“Educational Staff”). Die Zahl der Professor:innen mit Tenure ist in der Tat seit den 1980er Jahren rückläufig. Allerdings wird auch in der FIRE-Statistik nicht zwischen Tenure-Track-Faculty und anderen Lehrenden (die natürlich auch “Professor” im Titel haben können) unterschieden. FIRE scheint (nicht ungerechtfertigterweise) mit “Professor” einfach “eine:n am Campus Lehrende:n” zu meinen – und das tun die meisten Statistiken über die McCarthy-Ära auch. Daher halte ich den Vergleich hier für gerechtfertigt.

ENGLISH VERSION:

After a lecture earlier this month, a gentleman approached me about my book and accused me of “downplaying” the problem of free speech at US colleges and universities. He hadn't read my book, but he had "read about my book" – and based on some of the reviews I’ve seen, I can understand why he might have come away with that impression of my book. I don't want to misrepresent his accusation, but I can't remember the exact wording. As far as I understood, the trivialization he was concerned with was the following: there is a left-wing culture of censorship in American colleges. In recent years, “hundreds” of professors (conservative or otherwise offensive to the left mainstream) have fallen victim to it. He quoted the numbers from an article in the Boston Globe — a statement by Steven Pinker and others on the establishment of some kind of working group on academic freedom.

I don't want to offend the gentleman, and it does him credit that he (as he wrote me in the meantime) is reading my trivializing little book. But I found both the statistics he quoted and the way he quoted them extremely instructive for the cancel culture discourse in Germany (and to some extent the US). And that's why today I want to take a closer look at the data he put forward. I mention the gentleman not to in any way defame him but because the data he was referring to was in the article to be used by people like him. People who are concerned about academic freedom and who reasonably enough think that a piece by Steven Pinker in the Boston Globe is an objective source of the state of freedom of expression in the US.

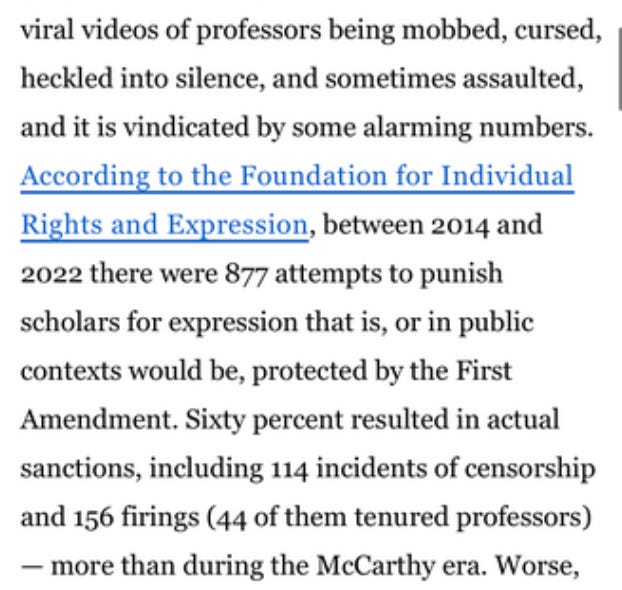

Here is the passage from which my interlocutor derived his understanding of the dimension of the problem:

I completely understand why my counterpart interpreted these numbers in this way. But the question, of course, is whether the numbers are accurate - and whether they mean what this text implies they mean. The article diagnoses a “disenchantment” among “Americans” with regard to their universities – but when you click on the link the authors provide, you will see that the Gallup poll referred to by the them actually indicates that it is Republicans in the US who have sharply more negative feelings about universities than they did only a few years ago. From the outset, alienation of right-wing US voters is equated with alienation of Americans as such. “No small part in this disenchantment is the impression that universities are repressing differences of opinion, like the inquisitions and purges of centuries past. It has been stoked by viral videos of professors being mobbed, cursed, heckled into silence, and sometimes assaulted, and it is vindicated by some alarming numbers.” What the authors mean is - let's be clear - left-wing "cancel culture", which is compared here with "inquisitions and purges of past centuries" - Torquemada but with they/them pronouns.

The article speaks of “156 firings” “between the years 2014 and 2022” – that is just over 17 per year.(1) “More than during the McCarthy era,” the article notes. The McCarthy period spans the years 1950-55 (or 1947-1956 if one assumes a cultural phenomenon (Red Scare) rather than the central figures). During that period, McCormick and Holmes counted “about 100” college and university professors in the US losing their jobs (compared to 500 school teachers, for example). Those numbers, I should note, are also difficult to collect – it’s been a long time, there were issues of sexuality tied into many of the cases which made people reticent to speak about them for long, etc.. So we’re comparing one very squishy number to another. Nevertheless, it can be said: The absolute numbers that FIRE provides do in fact exceed those from the McCarthy era - depending on which years are counted, the emissions per year in the McCarthy era may well have been higher (by exactly that to be able to answer, we would have to be able to see the database that Pinker et al use here as a basis).

Still, as bad as McCarthy, or almost as bad as McCarthy is bad enough! But firstly we should also consider the denominator: According to the Department of Education, around 1950 there were just about 1800 universities and colleges in the US. Today there are between 5,000 and 6,000 (depending on which institutions you count and which not). The number of teachers at these campuses jumped from 190,353 to 987,518 between 1950 and 1990 alone – a fivefold increase. Today, the number of “professors, associate professors, assistant professors, instructors, lecturers, assisting professors, adjunct professors, interim professors” stands at roughly 1.5 million, according to the Department of Education.(2) This creates a statistical problem: something that happens to 100 people out of 190,000 is clearly more common than something that happens to 156 people out of 1.5 million. The phrase “worse than McCarthy” seems calculated to confuse the absolute frequency with the relative frequency of a phenomenon. If the frequency with which these kinds of firings occur were truly worse than McCarthy, the number would – by my calculation, so please check my math – have to be something like 789.

But indeed: “more than McCarthy” may be true as a purely statistical description (more on that later), but this form of presentation seriously skews the data. When we warn of a new frenzy of censorship and moral dictates, especially in Europe, one has a pretty clear idea of who is censoring and why. Young, “woke” students censor conservative professors, often simply for statements they do not like. The gentleman who confronted me with this statistic seems to have understood it in the same way: For him the left-wing culture of censorship, which I allegedly downplayed, was based on woke, “SJW” politics. And I don't think it was because he misread the text - he just picked up correctly on what Pinker et al clearly suggest. But the FIRE-list doesn’t just count those kinds of cases, it endeavors to chronicle all cases where someone loses their job for speech that could arguably be protected under the first amendment. It is somewhat dishonest to misinterpret conservative censorship of left-wing professors as evidence of a left-wing censorship culture. This is exactly why the Pinker-text invokes McCarthy: the authors want to suggest that all 156 cases come from the same ideological direction – as they indeed did during McCarthyism. But: if in 1951 a professor was (illegally) ousted from office for eloping with the dean's wife, he would not be counted as a McCarthy victim. In 2020, a professor like LD Burnett could be fired for criticizing her university administration’s proximity to the Trump-orbit. And her case would show up as evidence that left-wing censorship was out of control.

Now we come to the most important aspect: the numbers themselves. I've screenshotted the passage in question, so unfortunately you can't click on the link. That's a shame, because the link is somewhat striking: it doesn't lead to an evaluation of data in which we can then read about the 44 de-tenurings, 877 "attempts to punish" and so on. Rather, it leads to the search engine of the FIRE Foundation “Scholars und Fire”-Database itself. So, as inclined readers, we can either work out these numbers for ourselves - or we simply have to trust them.

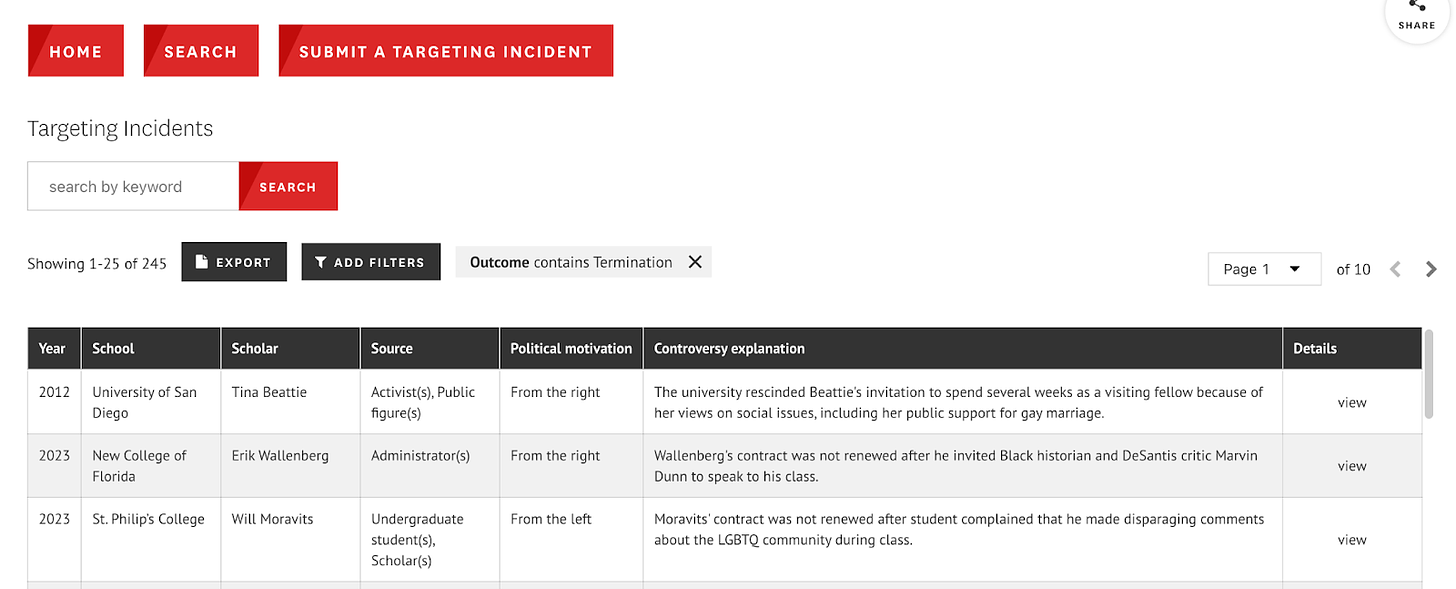

I should say right away that I find the Foundation's main concern — to identify incredibly powerful institutions that are often far too arbitrary with their workforce — absolutely important. However, I think that the search engine that FIRE offers seems to exist to be used in exactly the way that Pinker and colleagues did. And here I see a problem that I will try to demonstrate today. Together with my collaborator Eren Yurek, I reconstructed how Pinker et al might have collected this data. You searched for entries between the years 2015 and 2022 in which the metadata satisfies the situation “contains termination”.

Eren and I therefore used the same search mask and put together data sets for the individual years. Purely numerically, Pinker et al are right: the FIRE database lists 156 cases between 2015 and 2022 in which “termination” occurs in the metadata. Here is the distribution through the years:

First of all, one does not get the impression that the number is constantly increasing (which, to be fair, Pinker and colleagues also did not explicitly claim). The initial impression is rather that the number of firings is fairly consistently somewhere around 15-20 per year and that there is one massive outlier year. 2020 — the year of COVID, lockdowns, Black Lives Matter, presidential election, “Stolen Election”, the year we all sat at home and could only let off steam on social media, and where all teaching was via Zoom — presents, perhaps unsurprisingly is the (provisional) high water mark of this statistic. It was clearly a pretty bad year, and if warnings of a deteriorating climate for academic freedom is justified, this year most clearly bears them out Let's take a look at the cases.

Of the 37 cases listed for 2020, 29 involve consequences following complaints “from the left,” according to FIRE. However, these range from cases that are absolutely worth discussing (a single use of the “N-word”) to those that cannot really be politically located. For example, the fact that Professor Diane Klein (University of La Verne) had to leave because she suggested someone assassinate her dean, or that Thomas Brennan (Ferris State University) was fired because he questioned the reality of the moon landings and nuclear tests in confused posts really has nothing nothing to do with “right” or “left” positions – and their universities probably didn’t throw them out because they were “too conservative” or anything of that kind. One important note: a total of 13 of the 37 professors involved had tenure – so they were supposedly non-firable.

If you look at the individual cases, you will quickly notice that the problem with these numbers is not that any gross statistical error is being made here, but rather that at every step the numbers are tweaked a little in order to push the overall number a little higher. Of the 37 “fired” professors, two are still in office – we assume that the database simply has not been updated. Another left her job for a new one but was not fired, according to her employer. 2 others are not professors at all, but were doctoral students, who were thrown out of a doctoral program; another case has to do with a postdoc. In the well-known case of a classicist in Princeton, a first leave of absence took place in 2018, the firing in 2022. FIRE lists his controversial statements in 2020 and suggests that he was thrown out because of them. The allegations of sexual harassment, which the university gave as a reason for the resignation, and the years in which these were relevant are not on the FIRE-list.

In another case, colleagues prevented a professor from being promoted to a decanal position (the database considers this a “firing”), a few years later she simply took a job at another university. Two others went on leave without pay, but appear to have kept their jobs. In all, 8 of the 37 eventually got their jobs back, either after public pressure or after lawsuits.

Many others never resigned. Their contracts were simply not renewed. Which of course can also be dangerous, except that causality can be extremely difficult to establish — and very easy to assert. In total, 6 of the 37 are “adjunct professors”, who are not at the university full-time, but are only employed on a course-by-course basis (an utter horror of the American university system, by the way). Four others say their longer-term contracts were not renewed because they made statements their employers didn’t like. As a matter of principle, universities do not comment on such things, so there is no counter-version to hold up to their version of events. Many of these cases may point to legitimate grievances in American higher education — shameless exploitation, disloyalty on the part of the institution, and dependency — but not the same grievance. Here they are combined according to the principle "rhyme you or I'll eat you".

For example: 4 of the 37 were music professors at the College of Saint Rose in New York. The college fired the four professors (all of them tenured) in 2020 — the university says, as part of a cost cutting effort. The professors said it had to do with criticism of the music department for being "too white". On the FIRE website, the four are naturally part of the 37 — with the note that their cancellation came “from the left”. And Pinker et al apparently count the four among the 44 who would have lost their tenure for exercising their freedom of expression. However, that's a distortion of the facts twice over: the university says, as I mentioned, they had to save money (an absurdity, but a different absurdity than the one FIRE wants to document here). And moreover, the professors successfully sued against their resignation — the decision of the New York Supreme Court mentions the alleged political dimensions of the case only tangentially. Rather, the court determined that the “Music Department acted in violation of its own procedures,” “using inadequate, inaccurate, and misleading financial data, while retaining members of the same Department who were lower in rank and years of seniority, including those who had not been awarded tenure.”

So for those keeping score at home: Of the 13 professors with tenure who are on the FIRE list for 2020: 4 were cut for budget reasons, against which they successfully sued; one person has by no means lost their professorship but simply did not receive a promotion; one person changed jobs; two are on the list by mistake, they were criticized but kept their jobs. 6 cases remain. In 2020, the National Center for Education Statistics counted 189,692 professors (by definition with tenure) and 162,095 associate professors who also have tenure at most (but not all) universities. That means there are somewhere around 325-350,000 people with tenure, 6 of whom lost their tenure in 2020 – again, the year of COVID, lockdowns, Black Lives Matter, Presidential Election, Stolen Election, Zoom Meetings.

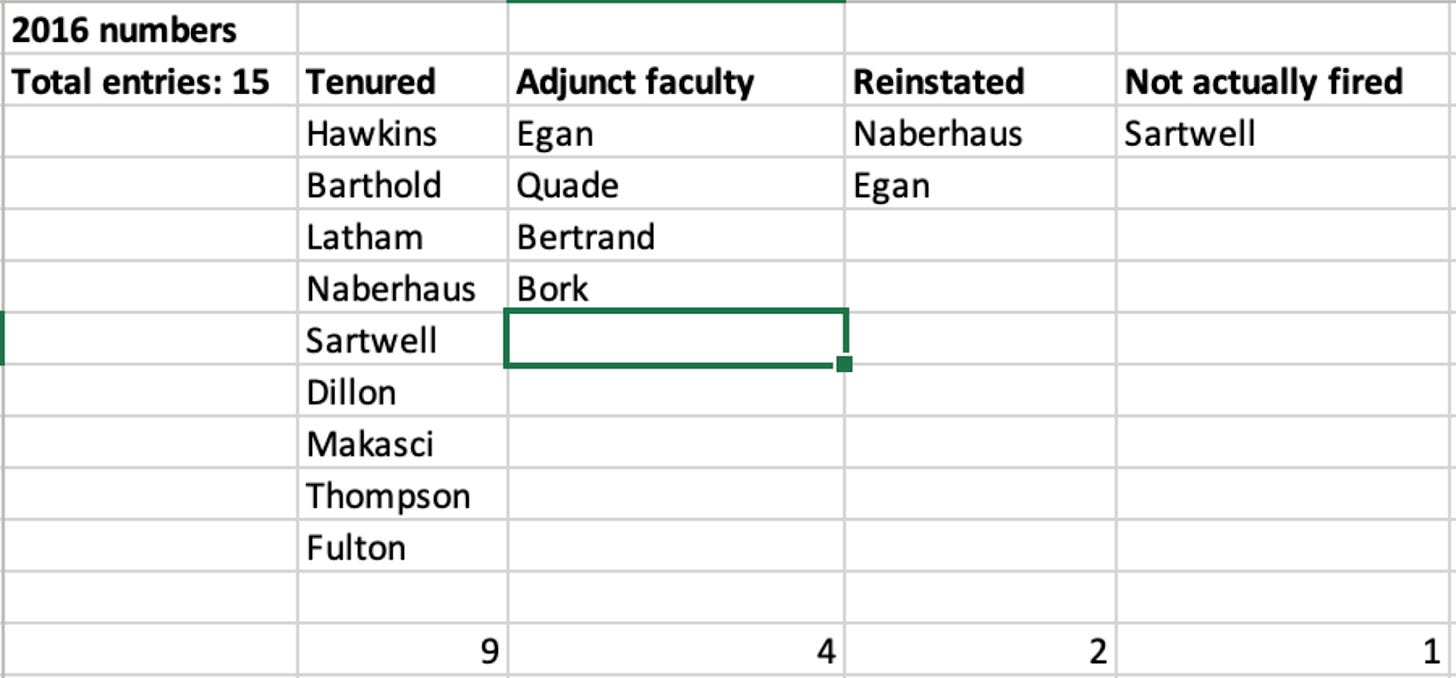

What's more, if we look for comparison at the numbers for 2016, we see that the numbers look very similar. The FIRE list for 2016 lists 15 professors who have lost their jobs. 9 of these had/have tenure. Of those, one wasn't actually fired. And, just in case it's of interest: Profs. Naberhaus, Barthold, Fulton, and Hawkins are listed in the FIRE list as canceled from the right. That’s 4 out of 9.

What is striking is the small number of adjuncts/lecturers — those people whose contract just wasn't renewed in the 2016 data set. I was at university in 2016, and I can't imagine anything less unfair about “adjuncts ” was handled. I have a suspicion that the "cancel culture" narrative just didn't really exist back then - and that people just didn't pay attention to such cases. The shift between 2016 and 2020 in the FIRE dataset appears to be due to this — often hidden — segment of the academic precariat. People have started to question and protest about such cases — but only when they fit into a political narrative.

Ultimately, you have to decide for yourself how you evaluate these numbers. You could of course say that one case is one case too many. But notice: many of these cases tell the story of a slow rift between a university and a particular professor. In some, I would immediately side with the professor (Lora Burnett was an openly left-wing voice on Twitter, her new university president a Trump-fan; some of the professors seem to have just written some ill-considered Facebook posts), in others I have to admit that I can understand the university's point of view: how do you deal with a colleague who disrupts public Zoom meetings with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories?

And this is precisely why the comparison with McCarthy is so blatantly flawed: first of all, there is a substantial difference when something is decreed and enforced by Congress, by the state, or whether something develops in civil society. A majority of Americans collectively chose in 2020 to think differently about and respond differently to racism (many, many conservative Americans, among them, by the way). Whether a vita falls victim to this (or, for example, to the fact that women are starting to report more openly about sexual harassment by professors) is something different than when governmental bodies with awesome punitive powers makes an example of professors.

But more importantly, if you look at the important cases during McCarthy, you'll notice how similar they were. The mechanisms of capture (Loyalty Oaths, denunciations from politicians, alumni, or the American Legion) were pretty much the same, the forms of adjudication (university committees, open hearings) were the same, and there was a very small set of possible outcomes (fortunately not resignation in most cases). In the case of the FIRE statistic, on the other hand, the data points on each of these is scattered to the extreme, even if we take the version of events of the “cancelled” professor as a basis. What Pinker et al intend for us to picture when we hear "156 professors" is probably a case like that of two professors at Louisiana State University: snarky, racist comments on Facebook about BLM; angry reactions from colleagues and students; resignation To be absolutely clear, these cases do occur in FIRE’s 2020 dataset. But they constitute (depending on how much faith we put the differing accounts) about a quarter of the 37 cases. The others seem to be largely intended to push the number up.

(1) I just went through the numbers again and the authors must mean “between 12/31/2014 and 2022.” Because if you add the year 2014, the remissions that can be read on the FIRE website are 165, not 156.

(2) It should be said that the statistics do not concern professors, but teachers (“educational staff”). The number of professors with tenure has indeed been declining since the 1980s. However, the FIRE statistics do not distinguish between tenure-track faculty and other teachers (who of course can also have “professor” in their title). By “professor” FIRE seems (not unreasonably) to mean simply “a faculty member on campus” – and so do most McCarthy-era statistics. So I think the comparison here is justified.