Artifacts of a Panic

It's been a minute since I last fed the Substack, but buckle up -- there's content incoming!

I just finished the copyedits of The Cancel Culture Panic, which started out as the English edition of my German-language book Cancel Culture Transfer, but evolved into a slightly different animal. (If you’re interested, you can pre-order it here.) Which is sort of the point of both versions of the book: people in different countries and publics spent the last few years talking about “cancel culture”, and anxiously looking at other countries to discuss its rise — but in a funny way each was having their own conversation about it. And perhaps even their own definitions? Not necessarily in the sense that they’d put something different down in a dictionary, but in the sense that what cases count and what doesn’t, where the phenomenon is centered and what’s considered marginal. Together with my Stanford colleague Quinn Dombrowski, I am currently analyzing the Wikipedia entries for “cancel culture” (or its national translations) in various linguistic versions. What examples characterize “Cultura de la cancelación” according to Spanish-language Wikipedia, vs. “Культура отмены” according to the Russian one, or “Linç kültürü”, according to the Turkish one.

[Oh, and if you say: “careful, Adrian, ‘Linç kültürü’ is actually an older description than ‘cancel culture’ and carries slightly different meanings!” then I’d answer: “YES, and this is one of the things you can read more about in my forthcoming book The Cancel Culture Panic, out from Stanford University Press in September!]

Many US or Canadian readers may be a little surprised to notice the subtitle of my forthcoming book — The Cancel Culture Panic: How an American Obsession Went Global. In the Substack over the next few weeks, I’d like to explore why I think it’s worthwhile looking at “cancel culture” discourses internationally. Why, in other words, did I choose to make The Cancel Culture Panic about a global phenomenon? “Wait, do they have cancel culture pieces in Germany?” American friends sometimes ask me. And oh boy do they ever! As I explain in the book, the “global” part is still a little tricky — it’s not that every country outside of the US has as many freak-out pieces about cancel culture, about wokeness and about college students doing college student thinks. But there are a bunch of countries that do.

In my book I try to answer two questions that turn out to be related.

Firstly: Where did the fixation on “cancel culture” come from, where the panics about “political correctness” and “speech codes” before it, and those about “DEI” and “CRT” after it?

And secondly: How come this fixation seems to travel so well, to countries that have very different university systems, much lower (or different) social media penetration, that had hardly any #MeToo or Black Lives Matter to speak of?

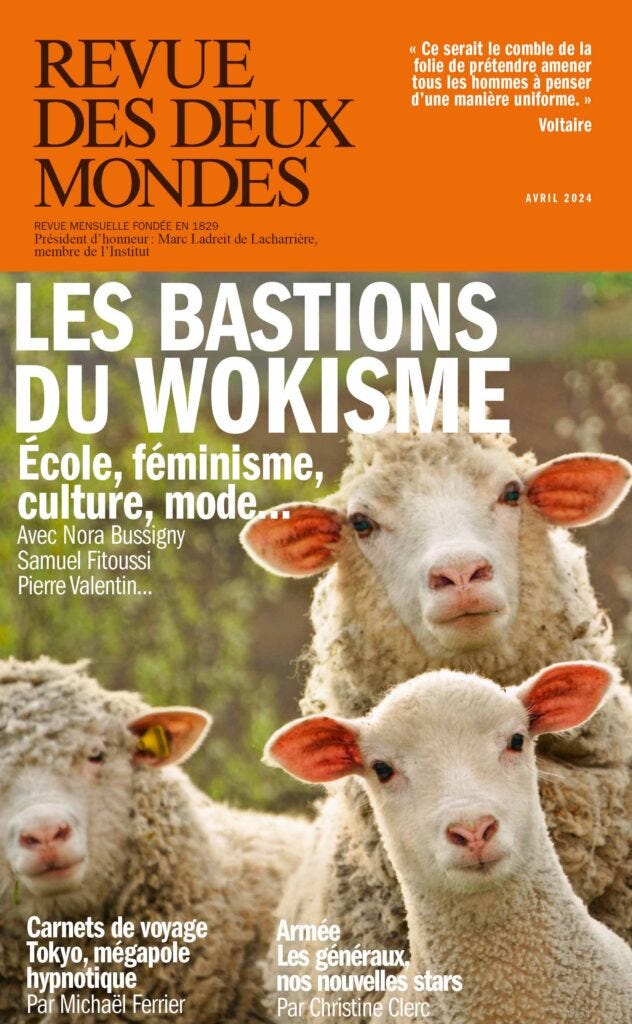

In order to give you a sense of this project, I thought I’d use this edition of my newsletter to do a close reading of a text that came out this month in the French periodical Revue des deux mondes. It’s a special issue, not on “cancel culture”, but on the preferred French version of the same discourse — le wokisme. Bastions of Wokism is the topic of the special issue, here’s the cover, which … really sets the mood.

For readers who have been spared this, just to give you a sense of how, um, robust the French discourse around “wokism” is, here’s a slide I use in presentations on the book — of French books about “woke” and “wokism”. This is not even close to all of them, I think it’s at best half of them. And these are only the ones that have “woke” in title or subtitle. There are dozens more about “identity”, “communitarianism”, etc., that are basically about this, but decided on a slightly different framing. And more to the point, these are all from the last two years. Every time I use this slide show, I have to add another title to the list.

Two things I’d like to note about these:

(1) Obvious stuff first: only one of these (Gad Saad’s book) is a translation. While there are some French books on this topic that have been translated into German, Dutch, Italian (though rarely English), French readers are having this debate largely mediated by texts written by French writers.

(2) I think the titles and subtitles are pretty informative here: there’s lots of talk about inquisitors and totalitarianism, sure. But what’s particularly striking is the language game about contamination, viruses and spreading sickness. If we want to be generous, we can say that we just had/are still lowkey having a pandemic, so maybe viral loads are on everyone’s mind. But certainly comparing your opponents to a virus isn’t perhaps the gesture of enlightened liberalism that the authors/editors think it is.

So in the midst of this veritable flood of anti-woke texts, the Revue des deux mondes decides to dedicate a special issue to the problem of wokeness. How do you say “no one’s talking about this” en français?

I’ll go through the opening editorial sentence by sentence, just because it’s short, and it’s really quite a fascinating document. I translated this on the fly, so please excuse any infelicities. You can find the original here, in case something doesn’t make sense. First, I’d like to point out that “bastions” is an interesting framing for “wokism”. You’re probably going to be able to guess what these “bastions” will turn out to be (The universities! The metropolis! The media!). But compared to the virus/contagion-framing in the book titles I showed earlier, there’s an interesting shift here. Bastions are, by definition, distinct from the land they survey and control. Which means, I think, that the editors of the Revue may be aware — on whatever level of consciousness — that most people don’t actually feel like a woke “inundation”, “virus” or “totalitarianism” is “contaminating” their local Super-U. So you have to make “les terres wokes” (as the subtitle of Nora Bussigny’s book puts it) extraterritorial.

Anyway, here’s how the editors start:

“It’s an evil wind coming to us from America. Insidiously, it gains power, fills the sails of the media, of school, of feminism, of universities or of artistic creation. Originally, the ambition was beautiful: to raise our awareness of social injustices, racial discrimination, and gender inequalities. But hell is paved with good intentions. Nebulously, wokism has mutated into an inquisitive, excessive and police ideology whose wrath falls on a West, necessarily privileged and racist, or on white males, necessarily libidinous and carnivorous. At all costs, we must re-educate our brains.”

So let’s get into this: Of course we have to start with the US — “an evil wind coming to us from America.” In general, Europeans are convinced that whatever they think of as “cancel culture” and “wokeness” comes from the US. In particular the French, right up to President Macron, tend to frame the arrival of “woke” ideas as a form of colonialism (while also pointedly refusing to feel bad about their own history of colonialism, but hey what are you gonna do?). France is, at any rate, positioned as the innocent receiver of bad American ideas — think of it as the Euro Disney theory of ideology. The US influence takes a “beautiful ambition” (“to raise awareness” etc etc) and perverts it into something sinister — re-education, I guess. On this telling, France, which was well on its way to being a post-racial utopia, was infected by bad and divisive US ideas. [Also, does the saying work differently in French, such that in French hell itself, rather than the path to hell, is paved with good intentions? Or does the Revue des deux mondes just not have a copyeditor?]

Next we get to “insiduously”/“nebulously”: this is something you see a lot in European texts about “cancel culture” and “wokeness”. They are describing something that is admittedly hard to substantiate, but rather than take that as a challenge and seek to substantiate the phenomenon, they lean into the insubstantiality. Things are mysterious, nearly imperceptible, a climate change, etc etc. — framings that appeal to people who share this kind of sense, and are not really meant to persuade anyone who doesn’t yet share it. Playing up the uncanniness of the processes described becomes a way for the writers (well, in this case, the editors) to not actually have to be concrete about the processes described. Who is doing what to whom and what does it mean? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯, but here’s an anecdote and a “nebulously”.

Anyway, on to the next two paragraphs:

“In this issue, we explore the Wokist strongholds, with their ukases and their great scissors. Like this demand for representativeness which targeted a play in Toulouse where protesters could not stand the text of a trans author being interpreted by an actress who was not.

In the United States, to be eligible for the Oscars, you must now successfully pass the ethnic and sexual quota test. In France, Arcom or the National Cinema Center are getting in tune, with standards of inclusiveness and diversity under their belt. In literature, is a man who speaks about women guilty of cultural appropriation? Should we hang the usurper Flaubert who wrote in the name of Madame Bovary? Should we burn books?”

A couple of things to point to here: first off, hats off to the editors on the “ukaz” comparison — “fatwa” I’d seen, but “ukaz” I hadn’t. Good one, guys. (For those of us not up on their Thesaurus-reading, an ukaz was a proclamation by the czar in Russia. You know, like a student saying they’d like you to use their pronouns. Exactly like that.) Then we get to the anecdotes — oh, the anecdotes. The “wokist strongholds” include — apparently — Toulouse, where protesters “targeted a play”. In just two paragraphs we went from hell being paved with good intentions to what — no offense to the theater scene in Toulouse — certainly doesn’t sound like an earth-shattering event. Anecdotes like this are the currency of the cancel culture panic more broadly, and I analyze them in depth in my book. They become decontextualized, smoothed through use and repetition, and are made to stand in for changes of a magnitude that seems ridiculously out of proportion with their initial import.

I really like the next paragraph, because you can see how the examples/anecdotes function. We start with a French example, which sounds like it happened. Then we move further away to the US, with an anecdote that very much did not. It is true that the Academy Awards have a inclusion-based eligibility requirement (you can read it here), but “must now pass the ethnic and sexual quote test” is hugely overstating it. You could fulfill this requirement as a studio/film company if you have “more than one” “in-house senior executives belonging to at least two underrepresented groups on their creative and development, marketing, publicity, and/or distribution teams.” This includes women, racial or ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ people!

The next example just says that some institutions in France are establishing practices to ensure diversity and inclusion, which is … bad somehow? And because the editors don’t seem to want to say why it’s bad, we get to the oldest chestnut of “cancel culture” / “political correctness” / “wokeness”-texts — the ones the author(s) make up. "In literature, is a man who speaks about women guilty of cultural appropriation?” Let me answer your question with a question: “Did someone say this? Would we take anyone seriously if we did?” “Should we hang the usurper Flaubert who wrote in the name of Madame Bovary?” Oh no, not Flaubert getting canceled for the thoughtcrime of writing about women. And finally: “Should we burn books?” All of this falls under: I see what you did there — at what level of literalness are we supposed to take any of these claims? Are the editors being funny? Fair enough, but if so: where did they stop reporting purported facts, and start being funny? What do they seriously believe is happening at the moment?

Finally, we get these two paragraphs:

“Often understood as a Parisian subject, confined to intellectual spheres, wokism also thrives in the region: “Wokisme basta”, we could read on the walls of the town hall of Bastia while the MJC (Maison des jeunesse et de la culture) from Mérignac recently offered teenagers a drag queen training course.

This sorting of ideas has its jargon, abundant and obscure, as a signal of its superior intelligence and our shameful ignorance: intersectionality, inclusivism, decolonialism, genderism, deconstruction, mysoginoire, androcentrism… Do you speak woke fluently? No, but this confusion weakens you, makes you feel guilty.”

Well, I’m glad we got the homophobia in there — just under the wire, chères éditeurs/éditrices! Just in case we were wondering whether this was also about gender — it’s France in 2024, so you bet your ass this is also about gender. The idea that there are two groups here — one speaking an incomprehensible “novlangue” (that’s the French version of Orwell’s Newspeak), and the other scrawling perfectly reasonable “Wokisme basta” on the wall of a town hall apparently? — gets at the really creepy cultural politics of this freak-out. Sure, you’re not feeling it in Nantes or Bourg-en-Bresse — but trust us, the woke are oppressing you from their oppression-bastions! Which, again, are the universities and probably Paris (just say “rootless cosmopolitans”, guys, this is taking forever!).