"A long way to go and a short time to get there"

Notes on the Trucker Movie Craze

[“Wait, there’s a pretty important election coming up, and you’re just writing about cars, Adrian?” Why, yes, yes I am! If you would like to get my takes on the election, you can head over to my podcast In Bed With the Right to hear me completely unspool and mock my left-wing cope. But on here, in order to not go completely crazy, I’ll be spending my evenings watching 1977’s second most successful film, Smokey and the Bandit!]

There’s no other way to describe it: between the early 1970s and the early 1980s, America went wild for the trucker. Truckers took over pop culture, CB radios became a widespread hobby, and trucker parlance (“ten four, good buddy”) entered the broader vernacular. That infatuation expressed itself in a group of sub-genres: trucker-country music (Terry Fell, Del Reeves, C.W. McCall), for instance, and the trucker movie as a subset of the then-emergent genre of the car chase movie.

This post is about the politics that roiled just below the surface of this trend. My overall point will be that they were surprisingly ambiguous — they represented an instinctually conservative way of grappling with recent societal changes without being (at least then) straightforwardly reactionary. It is mostly, however, about Smokey and the Bandit, which was released in 1977 and was the second-highest grossing movie of that year behind Star Wars. A movie I’d caught bits of in reruns for years, and that I finally decided to sit down and watch all the way through this summer while preparing my class.

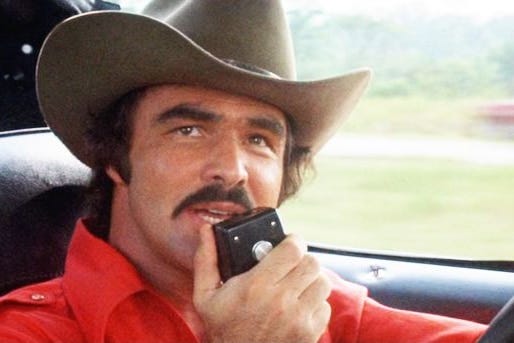

Smokey and the Bandit stars Burt Reynold as “Bandit” (real name: Bo Darville), who accepts a bet to transport 400 cases of Coors from Texarkana to Georgia (Coors wasn’t licensed for sale east of the Mississippi until 1986, so this was technically bootlegging). The plan: while his friend Cleedus “Snowman” Snow (played by country singer and soundtrack-provider Jerry Reed) drives the truck, Bandit drives blocker in his Pontiac, diverting law enforcement resources by leading cops on increasingly insane chases through the American South. Complications arise in in Texas, where Bandit picks up runaway bride Carrie (played by Sally Field), an act of kindness/horniness that puts corrupt Sheriff Buford T. Justice (Jackie Gleason) on his tail.

It’s a movie that’s about as in love as you can be with trucking, cars and the fellowship they apparently engender. The screenplay, a labor of love by first-time director Hal Needham is about 40% trucker lingo (“Ten-Four, Good Buddy”/“Ten-Ten on the side”), 20% the comedic stylings of Honeymooners star Jackie Gleason. And a good 40% more or less spectacular car chases: cars going fast, cars jumping over bodies of water, cars splashing down onto bodies of water. And so. much. CB radio. Just dudes on the radio. “Is that your name?” Carrie asks when Bandit introduces himself as the Bandit. “That’s my handle,” he replies. The movie is in love with handles, with the cant of the truckers, and a particular kind of gender performance that seems to go along with it. All of that is what this post will be about.

These movies are part of a neo-realist turn in 70s Hollywood. Even when they’re completely unrealistic, they deal with loans, payments, bosses, regulation. Truckers are where the mythology of the open road meets seeing actual working people on screen. Some of these movies are straightforwardly left-wing — Jonathan Kaplan’s 1975 movie White Line Fever ends with a trucker (“A working man who’s had enough!”, according to the film’s tagline) crashing his rig through a corporate logo — followed by a news announcer explaining that the local truckers have gone on strike in reaction. There’s a revolutionary undercurrent bubbling in these movies, but sometimes it’s a pretty confused undercurrent.

The Modern Cowboy and the Modern Communitarian

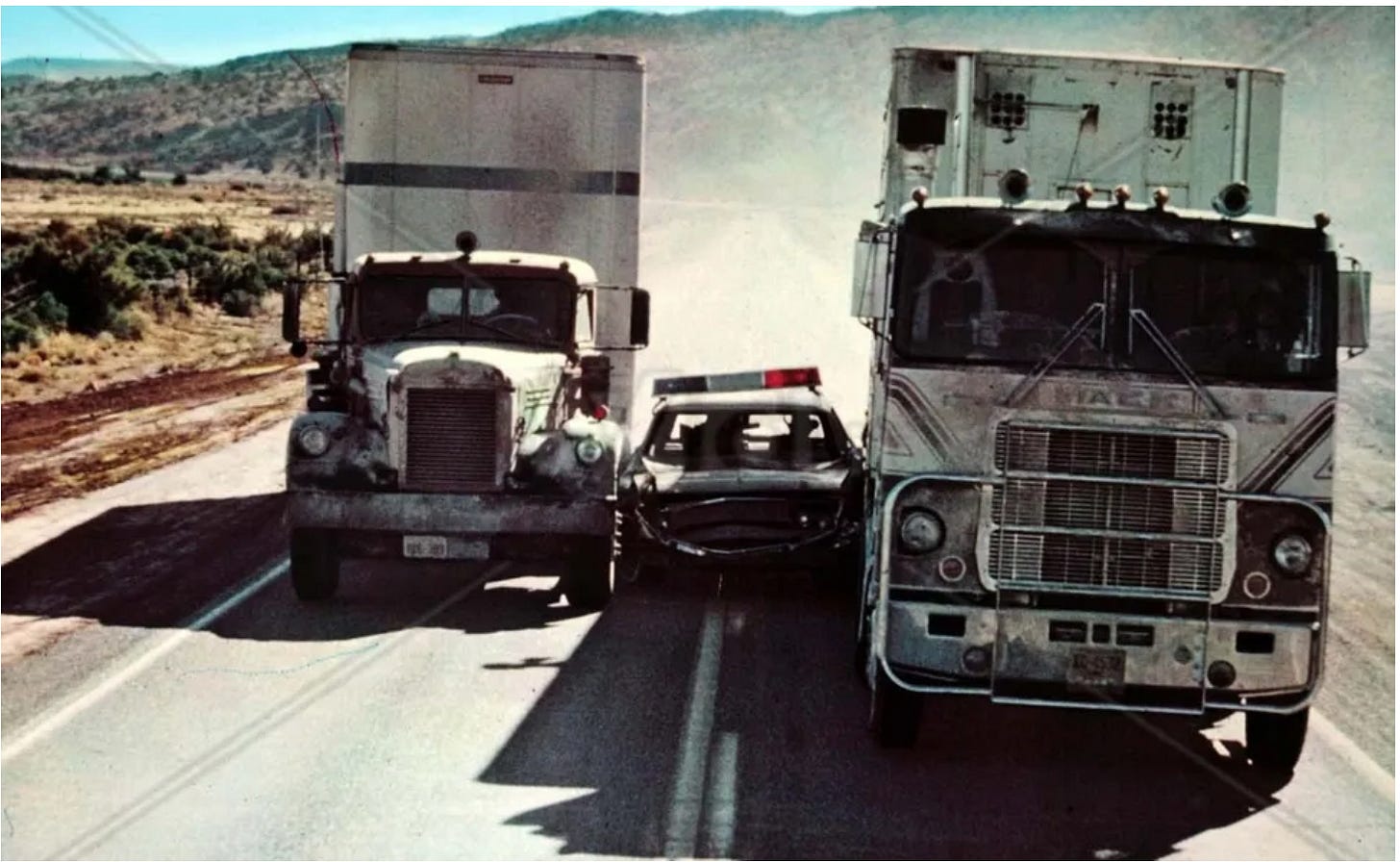

Trucking in 70s pop culture came in many flavors — most of the movies were action comedies (think 1978’s High-Ballin’), but there were also pretty serious thrillers focusing on trucks (1975’s White Line Fever). In the comedies as much as the action thrillers, the trucker combines two archetypes: he is a descendant of the lone cowboy, an outlaw and a modern-day drifter; and he is a radical communitarian. There is at the heart of the trucker movie a technological innovation that allowed for filmic innovation: the introduction of citizens’ band (CB) radio, which turned trucking from the lonely, exhausting and alienating experience we see in a movie like They Drive By Night (1940) to a loquacious, interactive ensemble experience we get in Smokey and the Bandit.

This is something that watching Duel for the last installment of this newsletter drove home for me: in that movie, Dennis Weaver emotes in his car by himself for 90 minutes, or at most screams at the implacable reflecting surface of a truck’s windshield. The whole movie is a monodrama, except one that happens to involve a big rig. It’s extremely claustrophobic and intense; what it isn’t, is snappy. Comedy, by contrast, is a dialogue-based genre and the CB radio becomes a way to introduce dialogue and larger casts into extremely lonely work without ever having to get out of the car. Whether it’s Buford T. Justice and The Bandit trading barbs by radio, or various truckers cheering each other on and colluding, Smokey is an ensemble piece in which most shots feature just one or two actors on screen.

Invented during World War II, the CB radio didn’t find widespread use until the early 1970s (it’s unlikely the Peterbilt truck in Duel has one, for instance). Apparently, the CB radio took off with truckers during the 1973 oil crisis — truckers used them to aid each other in finding gas stations with fuel, and later to warn each other of speed traps enforcing the 55 mph speed limit created in the wake of the crisis. Very quickly the CB radio became an organizing tool, helping to jumpstart and coordinate strikes, blockades and convoys.

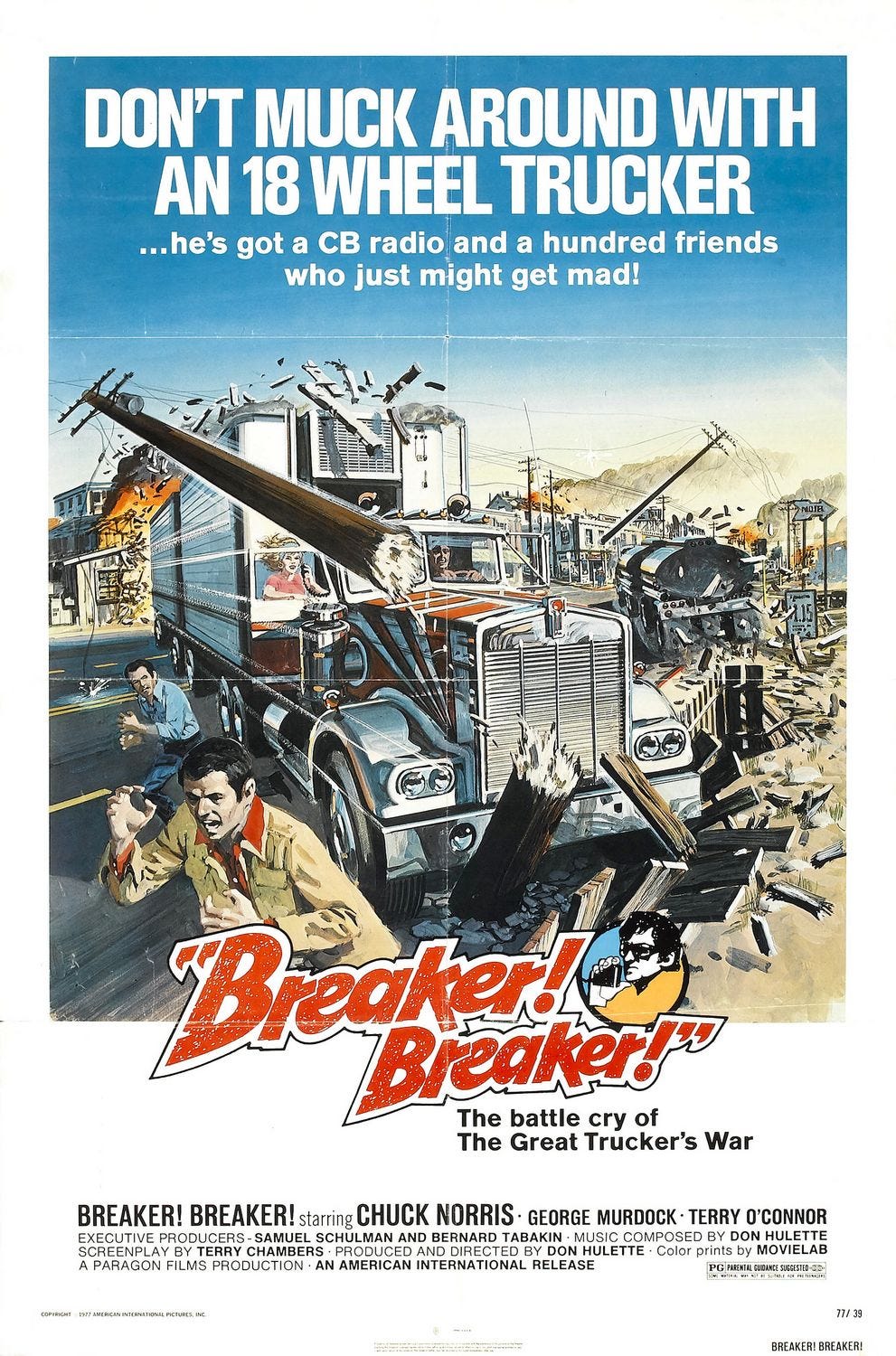

There’s a moment in many trucker comedies — there certainly is in Smokey and the Bandit — a moment when all seems lost, when the trucker is never going to make it in time, when The Law will catch up with him for sure. And at that moment, the other truckers show up. Jubilantly announcing themselves over the CB radio, they’ll swamp the bad guys, hide the truck, unload the cargo. These are, in other words, films about organizing and solidarity. That organizing can be joyous, but it can … easily have an edge. Just look at the tagline for 1977’s Breaker! Breaker!: “Don’t muck around with an 18 Wheel Trucker … he’s got a CB radio and a hundred friends who just might get mad!” While the trucker film is clearly a subgenre of the car chase movie, it is characterized by a very different relationship to the law, regulation and individualism.

A lot of these films rely on the motif of the convoy, a form of trucker protest that has a long history from the 1970s oil crisis all the way to the 2022 “Freedom Convoy” protest in Canada. And they are remarkably fluid in their political orientation — they were used during Teamster strikes in the 1970s, but many of them have also been very clearly right wing. My impression from watching way too many of these movies (and listen to too many country songs) in researching this post is that the coding in the 1970s was just a lot less clear: C.W. McCall’s Convoy (which inspired Sam Peckinpah’s movie of the same name in 1978 avoids naming an enemy beyond “bears” and “smokies” (i.e. law enforcement). The song is clear that the truckers are desperate and are having a hard time making money with their backbreaking work — but the song doesn’t say whose fault that is.

Free Agency

In this, too, the movie trucker has a dual role. He is aggressively blue collar-coded, but he is also a libertarian. It’s maybe too obvious a point to even notice, but almost all trucker films revolve around a run — that is to say, a long-haul drive far in excess of the limits imposed by federal law. The politics of the trucker movie are complicated, but at their core they draw their dramatic tension from an animus against the very regulation that is supposed to make these drivers’ lives safer. What is more: Like Bandit and Snowman’s run from Texarkana to Atlanta, all of these movies are tales of interstate commerce, and the Interstate Commerce Clause is of course the constitutional provision through which most federal regulation is justified. There is a “states’ rights” narrative and an undercurrent of resentment against federal overreach percolating just below the surface of these stories.

One word you’re almost never going to hear in these movies is “Teamsters” or “union”. Smokey and Snowman must be owner-operators, i.e. part of a growing segment of independent drivers. By the late 1960s, the Teamsters were in the grips of various (usually Jimmy Hoffa-related) scandals, and many truckers declined to join the union. Some of these truckers organized into the Independent Truckers Association, Roadmasters, Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA). In 1980, President Carter signed the Motor Carrier Reform and Modernization Act, which fully deregulated long-haul trucking. Interestingly enough, by that time the trucker craze had mostly died down. My point is: trucker films celebrate a kind of organic, spontaneous, anarchic solidarity among solitary owner-operators. They are about the specific struggle of the 1970s, without really ever naming it.

When Snowman asks Bandit why they’d do something as stupid as hauling beer from Texas to Atlanta in absurdly little time, Bandit replies: “For the good old American life: For the money, for the glory, and for the fun... mostly for the money.” The one thing he doesn’t name, in other words is: because we have to, because we aren’t turning a profit, because we can’t pay back our trucks if we don’t. The truckers’ overall affect in Smokey and the Bandit is almost annoyingly upbeat: everyone is constantly beaming into the camera, cracking wise into their CB, having just an absolute ball. The organizing drama around trucking throughout the 70s, the price shocks, stagflation and gasoline shortages is about how one can possibly make a living doing this. Smokey and the Bandit is almost psychotically Reagan-esque in trying to repress that anxiety.

Rising Again, but Different?

The trucker film, and in fact many car chase films of the era, were regional cinema, or at least aimed at a specific region: the old south. Just as Blaxploitation films made their money in very specific markets, these were films that recouped their budgets in the South — anything beyond that was gravy. Burt Reynolds once called White Lightning (1973) the beginning “of a whole series of films made in the South, about the South and for the South." Indeed, Smokey was initially released exclusively released in the South, opening in the North only after it had done extremely well in markets like Atlanta, Memphis, Charlotte, Dallas.

There’s an interesting story in that shift: the trucker was a successor figure to the cowboy, and many who wrote, directed and starred in trucker films (including, of course, Reynolds himself) had cut their teeth on Westerns. The Western had, as best as I can tell, been a supra-regional phenomenon. By the 1970s, after Nixon’s Southern Strategy and the emergence of the Dixiecrats, the frontier imagery and not-so-subtle Confederate nostalgia was becoming regionally specific rather than all-American.

The trucker movie craze coincided with the rise of trucker country music, and the sound of country is part of the hicksploitation vibes of the genre. Just as other specially targeted studio films (e.g. Blaxploitation) allowed for a sound not previously heard in Hollywood films, the car chase film became the number one place to hear a bunch of banjos going insane while people were doing wheelies on a median on screen. The peculiar pars pro toto by which some cultural signifiers became fused to working class identity independent of who actually employed them, the particular pars pro toto by which regional, racial, gender considerations seemed to influence whether you truly “counted” as working class (or as “the” working class): that faux populism runs through the trucker craze.

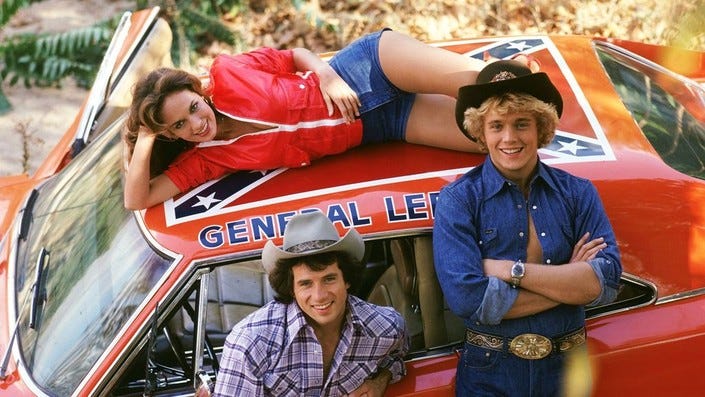

The Southern-ing of the trucker seems to be an aesthetic choice rather than a reflection of a sociological reality. Truckers were a pretty diverse workforce then, and they remain so now (58% white, according to the statistics I found); immigrants and outgroups found entry fairly easy. The Teamsters banned chapters that attempted to segregate. But the trucker-as-rebel figure wasn’t just regionalized as Southern, it was often implicitly Confederate-coded. I think this becomes most clear in The Dukes of Hazzard, which, although based on the 1975 movie Moonrunners, shares a lot of Smokey’s DNA, right down to the bootlegging and the corrupt Sheriff. For seven seasons, the Duke boys, Bo and Luke (except for a union-dispute season where they were replaced by their cousins Coy and Vance), drive around in a car named “The General Lee”, graced with a giant stars-and-bars on the roof, while their cousin drives one called “Dixie”.

“Someday the mountain might get 'em,” the show’s theme song (sung by Waylon Jennings) informs us, “but the law never will.” The song goes on:

“Just two good ol' boys,

Wouldn't change if they could,

Fightin' the system like a modern day Robin Hood…”

The Dukes of Hazzard doesn’t seem to distinguish between the Duke boys’ rebellion against an arrogant authority, between blue collar resistance to law enforcement and moneyed interest on the one hand, and the Confederacy on the other. This kind of Rebel-coding happens a lot in car films, and it’s all over trucker films as well. The way regional signifiers and class signifiers get repurposed as tokens of political reaction might remind you of a few things in 2024…

But Bandit isn’t Luke Duke. To be clear, there are a lot of Confederate signifiers in Smokey. The truck with the Coors has a manifest destiny graphic on its side, there are Confederate flags on various mudflaps. It’s not The Dukes of Hazzard by any stretch , but it’s not exactly difficult to read the rebel (cough) Bandit sticking it to federal authorities (cough) and sticking up for something that feels like a Lost Cause (cough cough) as a signifier for a Neo-Confederate masculinity — think Lynyrd Skynyrd with a better hat. And the fact that he appears to be an independent operator, and really a bit of a businessman, he may well unite in his persons the two groups that the Southern Strategy brought together: Southern whites and Northern business interests.

But I’m actually not sure that’s what’s going on in Smokey and the Bandit. There’s a veritable rainbow coalition aiding Bandit, who has Black, Asian and immigrant friends, and is cheered on by hippies, women truck drivers, prostitutes and college students, while Buford T. Justice is shown at every turn to be an unreconstructed racist, sexist of the kind Hollywood relies on when it needs to mark racism and sexism as an eccentric rather than inherent feature of US society. What is more, there is an emphasis throughout on filial piety, or lack thereof. Everyone keeps calling each other “son”, and they’re not usually saying anything nice once they do. There are several notable father-son pairings in the movie: Big Enos Burdette and his son, Little Enos initiate the bet with Bandit; Sheriff Justice has his dim-witted son Junior with him, who is basically his punching bag and is eventually relegated to just holding Buford’s hat after a tractor trailer has sheared off the top of their car.

As a result, the film keeps being about paternal disappointment. It’s not a theme so much as there are so many father-son pairs (literal and figurative) on the screen that people keep talking about sons not measuring up. Buford T. Justice in particular, when not busy losing various parts of his cop car in more-or-less humorous ways, can’t stop waxing patriarchal: “There's no way, *no* way, that you came from *my* loins”, he fumes at Junior. “Soon as I get home, first thing I'm gonna do is punch yo' momma in the mouth!” There is a weird anti-oedipal thing going on here, as fathers are forever abusing their sons. “She insulted my town, she insulted my son,” Justice fumes about Sally Field’s character, and then gets more explicit: “She insulted my authority, and that is nothing but clear and simple old-fashioned communism.” And just in case the social politics aren’t clear enough, the script has him add: “This happens every time one of these floozies starts poontangin' around with those show folk fags.”

I think what’s going on here is an attempt to do a regional variation on a counter-culture. The main rebellion of Bandit’s generation isn’t against the Feds, it’s against a generation of fathers who have identified their own authority with the law (“What we got here is a complete lack of respect for the law!”). And it’s probably no accident that in the final showdown happens on an Interstate heading towards Atlanta: after about an hour on small two-lane highways in some Southern backwater, Bandit’s Trans Am races down shockingly empty four-lane Interstates towards the boomtown of Atlanta, alongside truckers from various backgrounds. This is the New South, the film suggests, and it is here — away from the corrupt Sheriffs and the small bars where Nazi bikers beat you up — that men like Bandit find the allies they need in their rebellion.

While some trucker films come out of a New Hollywood idiom (Duel) and others are clear neo-Westerns (Peckinpah’s Convoy), a lot of them partake of a mini-genre only then emerging at the time: the stuntman film. There were about 15 years in the 70s and 80s, where an unusual number of people who had come up as stuntmen or stunt coordinators began directing movies: Clint Eastwood’s body double Buddy Van Horn, Dukes of Hazzard-alumn Craig R. Baxley in Hollywood, but also of course the likes of Bruce Lee, Sammo Hung, and Jackie Chan. Not all of their films featured cars — Willi Bogner, ex-skier who had done a bunch of ski stunts in James Bond films found a successful sideline making ski movies. But the car seemed most congenial to those moving from staging explosions to staging entire movies.

As it happens, Smokey-director Hal Needham was one of these director. Needham started out as a stuntman on various Westerns and TV Westerns, eventually becoming a stunt coordinator. One of the people he stunt doubled, as it turned out, was Burt Reynolds — the two formed a close relationship, Needham even moved into Reynolds’ guest house. The relationship between the two main characters in Quention Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is based on the relationship between Reynolds and Needham.

Needham started doing second unit work on two Reynolds-films (1974’s The Longest Yard and the White Lightning sequel Gator (1976). His contributions in both cases involved — you guessed it — the car chases. Needham would go on to direct his sort-of-roommate in five more films after Smokey — Hooper, Smokey and the Bandit II, The Cannonball Run, Stroker Ace and Cannonball Run II. Needham was also, according to his charming 2011 autobiography Stuntman! a bit of a racing nut himself — the stunt at the heart of Cannonball Run (using a fake and absurdly tuned up ambulance to do the illegal Cannonball Run in record time) is something Needham actually did, fake doctor and everything. He and Reynolds had their own NASCAR Team — Skoal and the Bandit. The sheer enthusiasm for cars, speed and bromance gives Smokey its infectious energy, but it also gives the film a serious case of underthinking what it is actually about.

As I suggested above, showing a trucker on screen in the 1970s was almost inevitably political. But Smokey certainly tries as hard as it can to not to stake out actual positions. Rather than speed limits and federal regulation, the restriction at the heart of the movie that sets the conditions for the central drama (the fact that Coors couldn’t be sold East of the Mississippi) feels quirky and almost random. Buford T. Justice’s vendetta against Bandit stems from Bandit picking up his son’s runaway bride. And even Bandit’s determination to win the gigantic betting sum of 80,000 dollars has nothing to do with economic hardship — he wants to buy a better truck, and even that seems like a bit of pretext. He’s The Bandit, of course he’s “gonna do the thing that can’t be done”!

The film has a kind of squeamishness that betrays that it knows things aren’t quite so simple. This is especially true when it comes to Needham’s specialty, the wall-to-wall vehicular mayhem. Smokey falls back on the cliché to have a cop crash his car in some absolutely insane way, and then lean out the window shouting something vaguely humorous. When I was little, this was an inevitable part of the syntax of chase sequences, and its purpose seems twofold: it’s a humorous button on a specific sequence, and it telegraphs that, improbably, perhaps impossibly, nobody got hurt. There’s something deeply unnerving about a world that is steeped in signifiers of authenticity, but that is also so gleefully fantastical — in its crashes, in its social politics, or in (an important aspect of a movie centered on a huge hulking truck) the fact that over the entire 28 hour drive none of the drivers ever seem to sleep. The world of Smokey is not fantastical enough for that to feel whimsical. And it contains, I suspect, a politics of its own. One in which impulsive, authentic masculinity does what it wants, endangers and maims. And is able to smirk about it.

Great piece! One question, on the politics of Smokey and the Bandit. Was the hyper-reactionary politics of the Coors family already present at this point? I get that the weird geographic restriction on the beer allowed for a kind of neo-bootlegging aspect, but hard to think of a more rabidly right wing and impactful political family than Coors. Maybe the Kochs and the Mellons, I guess. Also terrible beer, but that's a different topic.

This was a great read. A pleasure stylistically. This kind of cultural interpretation put me in mind of two books about the American imagination of personhood. First, Gunfighter Nation by Richard Slotkin (1992?), which swam in the waters of American visions of violence, manhood, and spiritual redemption for like 800 pages. Our mystic chords of frontier memory. Second, Decade of Nightmares by Philip Jenkins (2006) which focused on the 1970s as a cultural hinge period, and read signs of this transition in the movies of that time. The connection for me to your essay, maybe too simple a one, is in how much cultural borrowing is happening in these new works of art. They are always tapping into available reserves of cultural understanding. P.S. Jenkins has done lots of work on moral panics (including the 80s Satanic craze), which I'm sure you'd love! P.S.S. I waited in vain in this essay for a mention of Duncan Dudley's Six Days on the Road, a great trucker anthem.